The Nigerian Senate and House of Representatives have passed the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) in a bid to draw in more investment, from foreign and domestic sources.

The two houses approved the legislation on July 1. A reducer version of the PIB has reached this stage before, in 2018, but was rejected by the president.

Given that work on the PIB, in various forms, has been under way since 2007, rejection cannot be ruled out. This time around, the outlook seems more positive.

The head of the Senate, Ahmad Lawan, described passing of the PIB as a “tremendous and historical achievement”. He commended the House of Representatives for their support.

“We promised Nigerians that we will do our best to pass the PIB that has defied passage or defied assent. At least, the demons are being defeated in this chamber,” Lawan said. He went on to call for Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari to pass the PIB swiftly, once the legislature sends him the legislature.

Inching closer

“This is a very significant development and we seem closer than ever to seeing these reforms become law, after more than 20 years – but it’s not law just yet,” Bracewell partner Adam Blythe said.

“The bill proposes fundamental changes to all aspects of Nigeria’s upstream regulatory regime. Its passing will provide the industry with much needed certainty around taxes and royalties, along with reforming NNPC and establishing new regulators.”

The two houses passed different versions of the bill, Wood Mackenzie’s sub-Saharan Africa upstream research analyst Mansur Mohammed noted.

This will “require reconciliation before it is sent to the president for assent into law. So there is still outstanding work to do before the PIB becomes law, but we see momentum behind the bill.”

This might be the year that the PIB becomes law, the analyst said. “There is political alignment between the Houses of Parliament and the executive to enact the new petroleum law,” Mohammed said.

The National Assembly will halt for the summer in mid-July and return in early September.

Host challenges

The bill has five sections in 318 clauses: governance and institutions, administration, host communities development, petroleum industry fiscal framework, and a final miscellaneous provisions part.

There were challenges in the legislature last week, in particular around Clause 240, which focuses on the amount of revenues that should go to host communities.

The PIB had intended to pay 5% for local development funds. Northern senators pushed for a lower rate, of 3%.

Politicians from the south opposed the move with a number of – largely People’s Democratic Party (PDP) senators – demanding an increase. Senator George Sekibo, from Rivers State, went so far as calling for tougher voting restrictions.

Lawan reminded Sekibo that communities also stood to gain from cash stemming from gas flaring. Clause 52 sees “all monies” from gas flaring to go into environmental remediation for host communities.

Sekibo withdrew his objection.

Asharami Energy’s head of commercial and business development Mariah Lucciano-Gabriel saw the host communities payment as positive.

“This should, hopefully, facilitate stability in the Niger Delta region and promote sustainable community relations. The latter is critical to ensuring hitch-free operations across the value chain,” she said.

“To optimise and make this provision effective, we will need transparent administration of the fund, with the strictest levels of governance in place.” Asharami is an upstream unit of Sahara Group.

NNPC moves

One of the dramatic changes comes in reforms to Nigerian National Petroleum Corp. (NNPC) with Clause 53. The Minister of Petroleum Resources – another of the hats worn by President Buhari – will incorporate NNPC as a limited liability company within six months of the PIB passing.

The aim is to strengthen accountability and transparency at NNPC.

One of the clauses approves NNPC to fund exploration in frontier basins with 30% of its profits from production sharing, profit sharing and risk service contracts.

Clause 4 of the bill would establish the Nigerian Upstream Regulatory Commission, which would act as a technical regulator. Clause 29 establishes the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority.

Talking terms

Representative Mohammed Monguno, who led the committee on the PIB, said the bill would align Nigeria with international opportunities.

WoodMac’s Mohammed noted challenges to Nigeria’s outlook. “Although the bill is on the final stretch, Nigeria’s petroleum industry faces significant threats to long-term oil demand. It is, therefore, necessary for the government to move at pace to attract investors.”

The PIB can play a role in securing investments from majors, he said, despite their net zero targets. Wood Mac said the bill would resolve some uncertainties that have prevented investment in the upstream, gas, midstream and downstream.

The bill lowers royalties and tax rates, Wood Mac said, while marginal fields and local companies should also receive improved terms.

Asharami Energy’s Lucciano-Gabriel said the PIB reduces royalties for small onshore production sites, of less than 10,000 bpd. Indigenous companies dominate this space.

“This was previously reserved for actual ‘marginal field’ holders as opposed to any field with marginal production. I believe this will help bring fields considered marginal into production as it will change the economics significantly to go from 20% royalty rate to 5-7.5%.

Royal compromise

Bracewell’s Blythe also highlighted changes to the royalty proposals. “While the final details are still being reviewed, it appears that the government has moved back slightly from last year’s adoption of new and increased royalties, particularly in the deep offshore.”

He attributed this to the need to secure international investment at a time of reduced capital spending and energy transition concerns. “We can expect upstream participants to be analysing these new fiscal terms, assessing their international competitiveness and whether they are sufficient to sanction some of Nigeria’s long awaited developments and projects.”

The PIB changes did not impress Capital Economics’ Jason Tuvey. The bill “probably comes too late to propel a marked turnaround in the country’s oil sector and will not resolve many other issues afflicting the economy”, he said.

Major appeal

Concerns around oil demand peaking and stranded assets makes countries such as Nigeria less attractive than low-cost Middle Eastern producers.

Tuvey also raised other problems around Nigeria’s outlook. There is little sign the authorities intend to tackle the country’s overvalued exchange rate, capital controls and security issues, he said. “As a result, we remain downbeat on Nigeria’s growth prospects.”

Also sceptical was David Thomson, vice president at Welligence Energy Analytics.

There does seem to have been tangible progress, he said, but “the devil will be in the detail. Obviously the industry will welcome some sort of finality and certainty over terms. But indications are they may be quite harsh and if that is the case, we wouldn’t expect any rush to invest in Nigerian deepwater in particular.”

There have been some positive signs lately of interest from majors, though. While they continue to sell down onshore and shallow-water assets, there are signs of continued interest in gas and deepwater plans.

Shell, ExxonMobil, TotalEnergies and Eni all participated in the signing of an agreement in May on OML 118. The new production-sharing contract (PSC) allows the foreign companies and NNPC with stability on a potential new project, the $16 billion Bonga South West Aparo (BSWA).

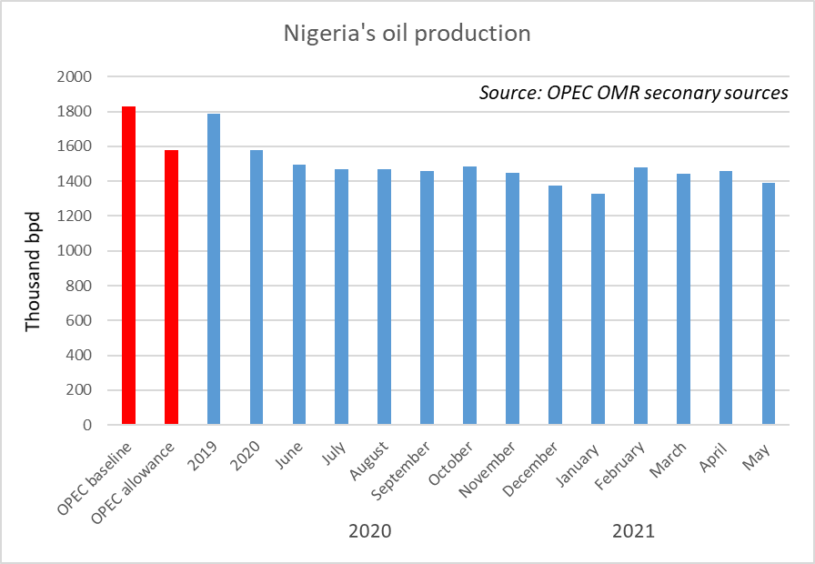

Nigeria’s production has fallen in recent times. The country has struggled to secure new investments but this may be about to change.

Updated July 7 at 1:09 pm with comment from Welligence’s David Thomson.

Updated July 7 at 1:09 pm with comment from Welligence’s David Thomson.