Nigeria has passed its Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), marking a major step in the country’s push to become more attractive as a destination.

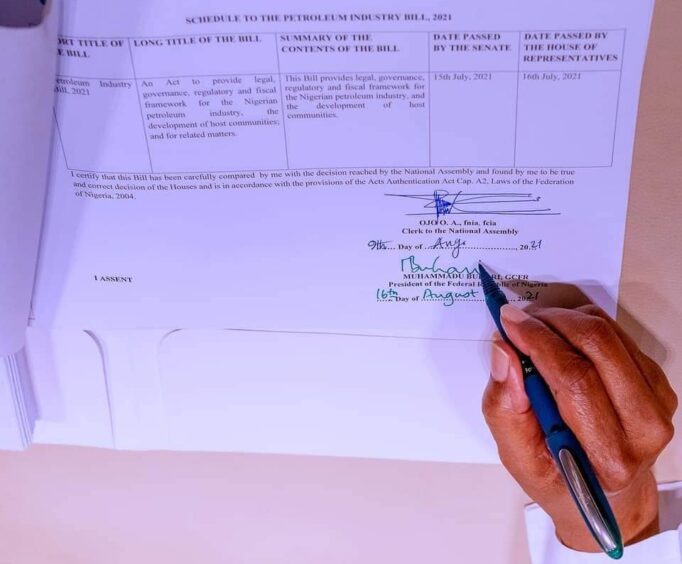

The legislation has existed in various forms for nearly 20 years and has had a number of stops and starts. Given this uneven track record, the speed with which the bill was settled by the legislature and then signed off by President Muhammadu Buhari is notable.

There is clearly political will behind the legislation. But will it win over investors?

Government take

“The PIA gives companies certainty on the regulatory regime, which has not been present for the past decade,” said Bracewell partner Adam Blythe. “This should help to clear one of the main blocks that have held back the sanctioning of new projects.”

The most important part of the PIA, he continued, was the impact on the fiscal regime. The PIA replaces petroleum profits tax (PPT) with a new hydrocarbon tax and also applies corporate income tax, while cutting royalties.

The new royalty system will allow the government to benefit if oil prices go higher, which may go some way to preventing tinkering with the fiscal system down the line.

“Overall, the government take has been reduced,” Blythe said. “Shallow and onshore fields have received the biggest net reduction in fiscal take. That looks like a strategic decision to improve tax conditions for onshore developments, where many Nigerian companies participate. Overall, the PIA makes Nigeria more competitive as an investment destination – it puts Nigeria in the mix.”

Changing the guard

International companies have played a major role in Nigeria’s development of its resources, but their prominence is fading.

Fitch Solutions head of oil and gas analysis Joseph Gatdula noted that while the PIA was significant, Nigeria would still lag hot spots like Brazil and Guyana. “Nigeria does have some of the best fiscal terms in sub-Saharan Africa, so regionally it is well placed. But on the global stage it is hard to see the case for capital shifting,” he said.

The majors have been selling down onshore Nigerian assets over the last 10 years. These fields are smaller and tend to be more challenging, not least because of community issues and insecurity.

Gatdula noted the act would not change majors’ minds on sales. “They are still going to be dumping low margin projects, especially where infrastructure is ageing and there is a drive to cut carbon,” he said.

Nigeria has struggled with gas flaring. As importers consider carbon border taxes, this may well become more of a problem for exports.

A recent note from Wood Mackenzie reported that for Eni, Shell and TotalEnergies, the emissions intensity of their Nigeria assets is substantially higher than the rest of their portfolios. “Divesting Nigerian assets is therefore one lever to reducing the emissions intensity of the overall portfolio,” director of consulting Simon Anderson said.

However, where the majors are selling out, indigenous companies are likely to benefit, the analyst continued.

There is growing interest in Nigeria’s gas resources, driven in part by the country’s drive to increase domestic power generation. Gatdula noted that the PIA would see gas pricing continue to be set by the government.

While the fiscal and regulatory side “is not ideal for investors”, Fitch Solutions expects investment to increase in gas infrastructure.

Big plans

One area that continues to be of interest to international companies is Nigeria’s deepwater.

The Fitch Solutions analyst highlighted Shell’s Bonga South West as the “bellwether project”. Shell has defined Nigeria’s deepwater as one of its nine core areas, where returns are strong and carbon emissions low.

“Bonga South West has been on the drawing board for a number of years and is the furthest along in planning. If this goes forward it will shore up the plans for other deepwater fields. That said, it is not going to go ahead overnight, we estimate it will reach FID in 2022,” Gatdula said.

Companies operating in the country will have to take a decision on whether to convert their existing licence into the new PIA format.

Initially, they have the option on whether to convert. As licences come up for renewal, though, the regulator will convert them mandatorily.

When to convert will vary case by case, said Bracewell’s Blythe.

“One consequence of conversion is that companies will have to hand back a significant part of their acreage. Companies also have to waive any ongoing court proceedings. They will have to decide whether changes in the fiscal terms are enough to compensate for what must be given up in a voluntary conversion,” he said.

The conversion process is as yet still somewhat unclear. Upstream players will watch the first few conversions closely for clues on how these might proceed.

On the rise

State-run Nigerian National Petroleum Corp. (NNPC) is also on the brink of major changes. How this may have an impact on how the company operates is also unclear.

Areas where foreign partners would be keen to see change would be NNPC’s ability to raise financing and meet cash calls. “Will NNPC be able to raise enough debt or sell crude to meet its joint venture cash calls, for instance? That remains to be seen and will depend on how NNPC is actually managed,” Blythe continued.

Gatdula expressed optimism that the PIA would help NNPC focus on transparency and profit. “This should translate into production efficiency, although it will need investment capital,” he said.

Fitch Solutions expects Nigeria’s production to rise, although reaching a top limit of around 2 million bpd. For the company to achieve this, growth would have to come from the deepwater fields.

To achieve this, the PIA must improve the relationship between NNPC and the foreign majors to unlock new investments.

Local friction

In terms of potentially difficult relationships, the challenge of host communities continues in Nigeria. While debates in the legislature touched on a number of issues, perhaps the most contentious was what sort of revenues should go to those living around production sites.

The PIA ended up setting this at 3% for host community funds, while directing 30% of NNPC profit oil and gas returns to frontier exploration. The latter is largely seen as a proxy for work in Nigeria’s north, where results have been underwhelming.

The PIA ended up setting this at 3% for host community funds, while directing 30% of NNPC profit oil and gas returns to frontier exploration. The latter is largely seen as a proxy for work in Nigeria’s north, where results have been underwhelming.

Some local groups in the Niger Delta have protested that they are getting too small a slice of the pie.

How the government oversees these funds and how successful they are in distributing cash will be critical. “If the trusts can be established quickly, create meaningful projects and engage local stakeholders, then the arguments of 3% vs 5% may quickly be forgotten.”

Another important note is that the PIA attempts to put the burden of facility security on local communities.

“Any repairs to oil and gas infrastructure (resulting from theft or sabotage) will come from that fund,” said Gatdula “That puts a mechanism in place to see communities police themselves, it attempts to put damage limitation at the grassroots level rather than on direct government intervention.”

Nigeria is poised for major change. The fact that the PIA was so long in coming has served to distract from the reality that how the act is implemented is even more important than the act itself.