Decisions from OPEC last weekend, and from Saudi Arabia in particular, overshadowed what could have been a major opportunity for three African producers.

The organisation has struggled this year to convince the market of the need for higher prices. Last weekend, at a meeting in Vienna, the group said OPEC+ would produce 40.46 million barrels per day in 2024.

The announcement came with provisos around production capacities, which OPEC will use for 2025 reference production levels. IHS, Wood Mackenzie and Rystad Energy will assess the members of OPEC, in a process co-ordinated by the secretariat.

The OPEC statement singled out Angola, Nigeria and Congo Brazzaville for particular attention.

It said Angola’s production plans for 2024 would be subject to verification by its three consultants before the end of 2024. Meanwhile, for Congo and Nigeria, the production level “may be updated to equal the average production that can be achieved in 2024”.

Number juggling

The OPEC statement noted that Nigeria planned to produce 1.578mn bpd in 2024.

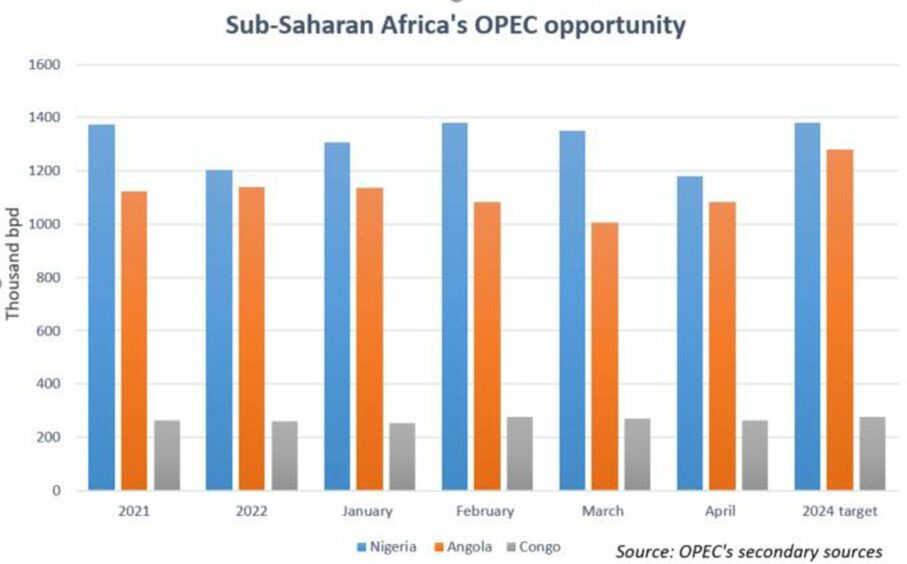

OPEC has based its 2024 expectations on Nigeria producing 1.38mn bpd, Congo 276,000 bpd and Angola 1.28mn bpd.

On the face of it, these are major reductions for the countries. In October, OPEC set Angola’s required production at 1.525mn bpd, Congo at 325,000 bpd and Nigeria at 1.826mn bpd.

On the face of it, these are major reductions for the countries. In October, OPEC set Angola’s required production at 1.525mn bpd, Congo at 325,000 bpd and Nigeria at 1.826mn bpd.

While the statement from OPEC appears to show an opportunity, FGE said, the organisation is actually just taking steps to base its quotas in line with reality. The statement for 2024 would suggest a 4.5mn bpd reduction.

“However, these reductions have simply brought output targets down to be more in line with actual output capabilities in many countries. Our forecasts had already been assuming an even lower output for those countries based on their current production levels and our capacity estimations,” FGE said.

With those countries consistently failing to meet their production quotas, the numbers have lost meaning.

“The deal announced at the weekend certainly creates an incentive for these three countries to try and demonstrate they can raise production before year-end, but we think they are unlikely to be able to manage it,” said Energy Aspects head of geopolitics Richard Bronze.

The three countries face “high natural decline rates and limited upstream investment. Nigeria also faces further challenges from political disruptions and strikes,” he said. It is these problems that have reduced production, rather than OPEC quotas.

Term-time squeeze

Obo Idornigie, vice president of sub-Saharan Africa research for Welligence, said Nigeria could “achieve modest improvements in production from the onshore and shallow water areas”.

The government has made some progress improving security in the Niger Delta, Idornigie said, particularly in the Eastern Delta.

“With these improvements, we expect a number of the smaller onshore operators will try and increase output from their respective onshore assets.”

The Welligence analyst also noted a $1.4 billion spending commitment from Chevron at its onshore brownfield operations, “could also boost near-term output. But, onshore and shallow water activity from the other Majors will remain modest at best in the near to medium term.”

It is the deepwater that has seen no new investments from international operators for some time. Idornigie said the majors were “managing decline from their producing assets. With no deepwater projects under development, we don’t even see tangible medium-term growth in output.”

Nigeria has big plans. Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) head Gbenga Komolafe, talking on Thursday to local journalists, said the country could produce 2.2mn bpd.

David Thomson, also at Welligence, said Angola and Congo also lacked scope to increase production.

“Angola does have a few bigger ticket projects”, Thomson said, such as Azule Energy’s Agogo and TotalEnergies’ Cameia-Golfinho. These, though, will “only help mitigate production decline when they start – three or four years down the road. But I can’t see Angola or Congo boosting output in any significant way, or indeed at all, ahead of the next OPEC meeting.”

Field management

Thomson said the sub-Saharan producers differed from the big Middle Eastern producers. Where countries such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have fine control over production, this is not an option for the African producers.

“They are in general pumping what they can. They are reluctant to switch off production as they may not be able to turn it back on down the line,” the Welligence official said.

Energy Aspect’s Bronze said the note on the three African producers was intended to make it “more politically palatable for these countries to accept a big reduction to their official quotas”.

“Our assessment is that Angola’s new quota is still well above its actual production capacity and Congo is broadly in line. Nigeria theoretically should be able to produce a little more than the new quota, but only if the new government manages to resolve all the political and technical issues, which seems unlikely.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by TotalEnergies

© Supplied by TotalEnergies