South Sudan has largely squandered its oil revenues, with International Crisis Group (ICG) suggesting the state be paid to not produce.

The report, Oil or Nothing: Dealing with South Sudan’s Bleeding Finances, notes that South Sudan secured prepayment credit facilities during the civil war. This involved advance loans from “a small group of commodity traders and commercial banks, piling up debt while hiding the country’s finances ever further from sight”.

While cash flowed into the government, various high-ranking officials diverted large amounts of the revenue. As a result, South Sudan often struggles to pay salaries.

Foreign funds

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) provided around $550 million in a process starting in late 2020. It only secured minor concessions.

The ICG report called on foreign states to bring more pressure to bear to reform South Sudan. The government should direct oil revenues back onto the books, with public disclosure of debt and revenues.

The report also called on donors to engage with commodity dealers and banks, who have provided critical financial support for South Sudan. The threat of regulation should be used to force traders to disclose payments. Banks and insurers should also be threatened with legal and reputational exposure, it said.

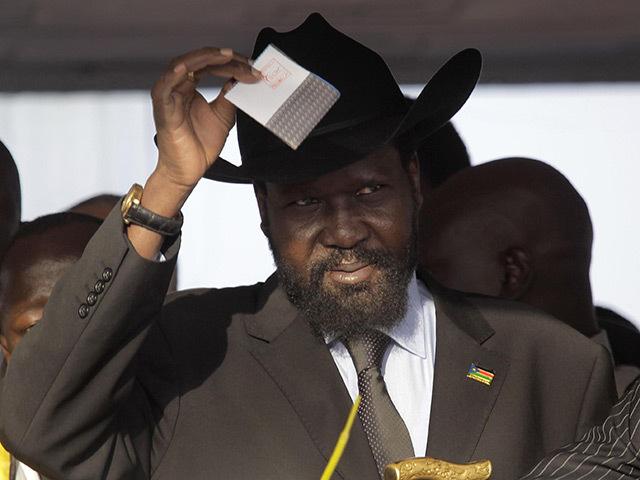

A dispute between President Salva Kiir and vice president Riek Machar in 2013 sparked accusations of an alleged coup and fed into a civil war. The two agreed to a peace deal in 2018 and a unity government emerged in 2020.

The state used IMF funds to pay government soldiers, the ICG report said, but not forces loyal to Machar.

“The pot of oil revenues claimed by those atop South Sudan’s system dramatically raises the stakes of holding power, accentuating the winner-take-all nature of South Sudanese politics,” the report said.

The president continues to control the oil funds. The constitution requires 5% of oil revenues go to oil-producing areas, but in reality often falls short.

State-owned Nilepet also acts to distribute funds, including to private security companies and militias.

Given the oil revenues, South Sudan has done little to develop other parts of its economy, the ICG said.

Barrel business

The report put total production at 150,000-170,000 barrels per day. Of this, 55-60% of proceeds go to the three producing companies. Another 28,000 bpd goes to Sudan to pay for pipeline use and a $3 billion compensation package. South Sudan expects to have paid off the compensation obligation by the end of the year.

This leaves South Sudan with 35,000-45,000 bpd.

Kiir has made various statements about dedicating oil flows to projects. In 2019, for instance, he set aside 30,000 bpd to support road projects with Chinese companies. He has also raised the possibility of dedicating another 5,000 bpd to paying salaries.

Other calls on the fund include commercial loan repayments, to Qatar National Bank, the Africa Export Import Bank and Sahara Energy. It owes $650 million to the Qatari bank, the ICG said, and at least $1 billion to commodity traders under pre-payment agreements.

South Sudan’s production is declining and recovery figures are low. One novel option suggested by ICG was that donors could provide conditional budgetary support to leave the oil in the ground.

The country’s revenues are relatively small. Donors are already working in the country. Furthermore, the oil revenues are helping entrench the conditions for conflict.

Donors could demand transparency in the spending of such funds. They could also encourage Juba to consider alternatives, such as agriculture or renewable energy.