A single US shale oil field is responsible for much of the past decade’s increase in global atmospheric levels of ethane, a gas that can damage air quality and impact climate, according to new study led by the University of Michigan.

Researchers found the Bakken Formation which lies under North Dakota and Montana, emits around 2% of the world’s ethane, roughly 250,000 tons per year.

“Two percent might not sound like a lot, but the emissions we observed in this single region are 10 to 100 times larger than reported in inventories. They directly impact air quality across North America. And they’re sufficient to explain much of the global shift in ethane concentrations,” said study author Eric Kort, assistant professor of climate and space sciences and engineering.

Bakken is part of a 200,000-square-mile basin that underlies parts of Saskatchewan and Manitoba in addition to the two US states and is one of the main areas of shale plays in the United States that have transformed the global energy market.

Between 2005 and 2014, the Bakken’s oil production jumped by a factor of 3,500, and its gas production by 180. In the past two years, however, production has plateaued according to the University.

Ethane is the second most abundant atmospheric hydrocarbon.

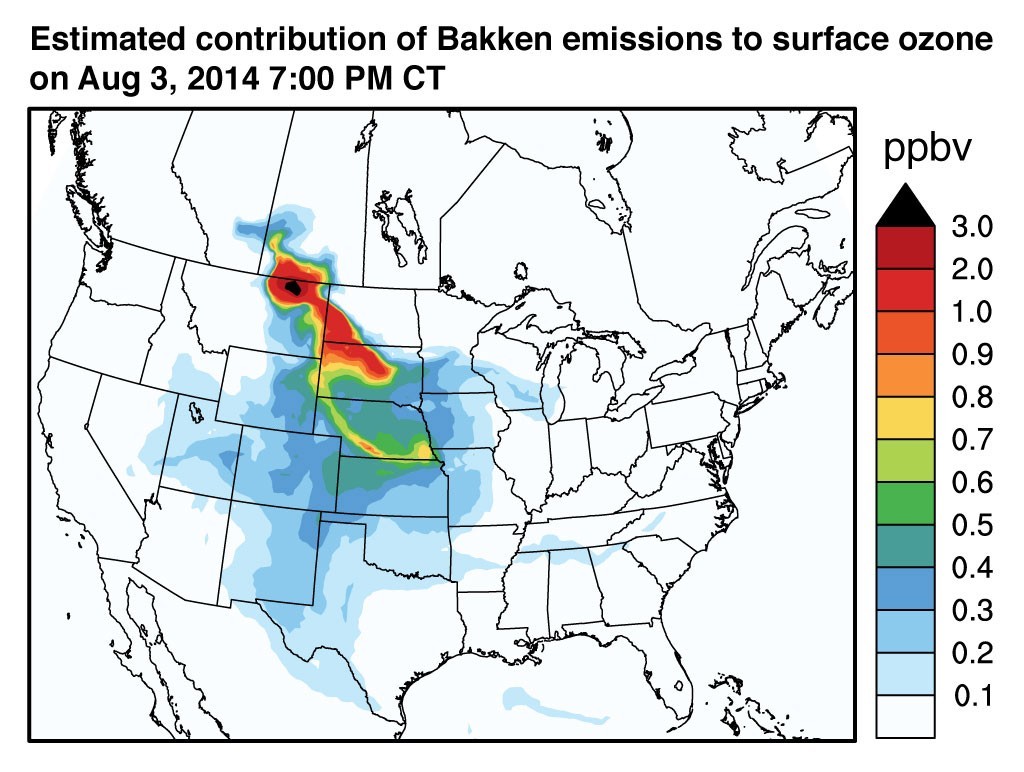

It reacts with sunlight and other molecules in the atmosphere to form ozone, which at the surface can cause respiratory problems, eye irritation and other ailments. It can also damage crops.

Globally, the atmosphere’s ethane levels were on the downswing from 1984 to 2009. Scientists attributed its declining levels to less venting and flaring of gas from oil fields and less leakage from production and distribution systems.

The gas gets into the air through leaks in fossil fuel extraction, processing and distribution.

In 2010, a mountaintop sensor in Europe registered an ethane uptick. Researchers looked into it and hypothesised the fracking boom in the US could be the cause. Ethane concentrations have been increasing ever since.

Researchers flew over Bakken sampling air for 12 days in May 2014.

“These findings not only solve an atmospheric mystery—where that extra ethane was coming from—they also help us understand how regional activities sometimes have global impacts,” said co-author Colm Sweeney, a scientist with the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder

“We did not expect a single oil field to affect global levels of this gas.”

Ethane emissions from other US fields, especially the Eagle Ford in Texas, likely contributed as well, the research team believes.

The findings illustrate the key role of shale oil and gas production in rising ethane levels.

The study is published in Geophysical Research Letters.

Also contributing were researchers from NOAA, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Columbia University, Stanford University and Harvard University. The research was funded primarily by NOAA and NASA.

Recommended for you