The hints of a pipeline spill are subtle: the hiss of rushing fluid, a streak of rainbow sheen. Tucked far below ground, a ruptured line can escape notice for days or even weeks, especially in the backcountry, where inspectors rarely venture.

Regulators in the waning hours of the Obama era wrote rules aimed at changing that, and the industry is looking forward to the new administration rolling them back. The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration “has gone overboard,” said Brigham McCown, a former head of the PHMSA who served on President Donald Trump’s infrastructure transition team. “They built a Cadillac instead of the Chevrolet that Congress told them to build.”

The oversight agency, an arm of the U.S. Department of Transportation, is just one of many where Barack Obama’s policies are in the Trump team’s sights. The battle lines are predictable, with companies on one side and safety and environmental activists on the other. What’s particularly worrying the latter is timing, because the rules could be upended as new shipping routes go into service across the country.

The president, a fan of fossil fuels, has revived two controversial pipelines, TransCanada Corp.’s Keystone XL and Energy Transfer Partners LP’s Dakota Access. They would add 2,300 miles (3,700 kilometers) to the U.S. network with room to transport 1.1 million barrels a day. As it is, there are more than 200,000 miles of pipe cutting across the country carrying crude, gasoline and other hazardous liquids — about 18 billion barrels worth annually. Many other projects are on the map; in Houston alone, planned lines are expected to increase capacity by 550,000 barrels a day in the next few years.

“I’m terrified about what is going to happen under Trump,” said Jane Kleeb, president of the Bold Alliance, a coalition of groups opposing Keystone XL. “My worry is that they will just budget-starve PHMSA.”

Read More: Why Keystone counts

While Obama was president, the PHMSA budget grew by 61 percent. Then, seven days before Trump’s inauguration, the agency finalized a rule toughening up inspection and repair demands, mandating, for example, that companies have leak-detection systems in populated areas and requiring they examine lines within 72 hours of flooding or another so-called extreme weather event. The American Petroleum Institute, the oil and gas industry’s main trade group, characterized it all as overreaching and unnecessary.

The rule was set to take effect in July. The Trump administration slapped a freeze on all regulations written under Obama that haven’t yet gone into force.

Pipeline leaks are pretty much inevitable; one ruptures every day on average in the U.S., though in the majority of cases the discharge is less than 5 barrels, or 210 gallons.

But big ones can be destructive, and deadly. The 2010 failure of an Enbridge Inc. line sent more than 20,000 barrels of heavy crude into a Kalamazoo River tributary, coating birds, muskrats and other wildlife and closing the river to recreational activity for 22 months; Enbridge agreed to pay $177 million in fines and to boost safety in a settlement with the U.S. Justice Department, which said it took the company 17 hours to notice the breach.

Last October, an explosion on the largest U.S. gasoline pipeline killed one person, injured several more and temporarily cut off the fuel supply along the East Coast. In December, about 150 miles from a Dakota Access protest camp, a pipeline spilled 4,200 barrels of oil and was held up by environmentalists as a harbinger of what’s to come.

Government statistics show there has been recent improvement in incident rates: In 2016, the number of accidents fell for the first time in five years, to 417 from 462, with total volume spilled declining 27 percent and the cost of related property damage dropping to $183 million from $257 million. The PHMSA wouldn’t speculate on the reasons and pro-regulation forces were reluctant to draw conclusions based on a single year’s statistics.

From the perspective of the Association of Oil Pipe Lines, the network is safer than ever, with problems quickly contained. The trade group credits improving technology and industry vigilance in adhering to the PHMSA’s self-policing policies, with operators responsible for reporting leaks and required to design and submit for approval integrity-management plans for keeping their lines as leak-free as possible.

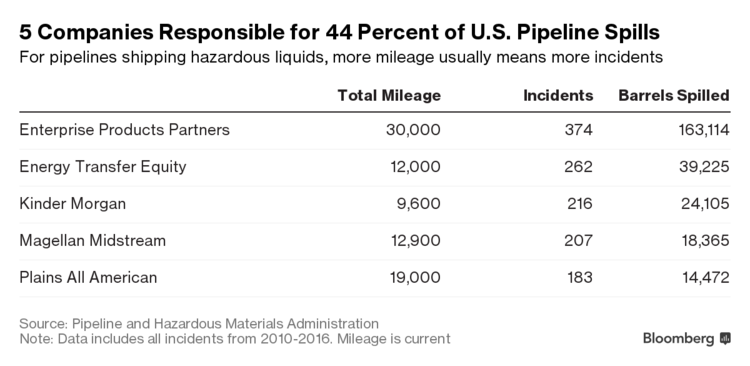

Since 2010, five companies have been responsible for 44 percent of all hazardous liquid spills, according to a Bloomberg analysis of data collected by the PHMSA. The remaining were split among more than 60 companies.

Those with vast assets tend to report a higher number of incidents, of course. The biggest, Enterprise Products Partners LP, ranked first between 2010 and 2016. But the amount spilled comprised “a tiny fraction” of the total shipped, said Enterprise spokesman Rick Rainey.

Mileage, though, doesn’t always correlate with incident rate. Energy Transfer Equity LP’s system, which will include the Dakota Access if opponents don’t block it, is 40 percent smaller that Enterprise’s and ranked No. 2 in incidents and spill amounts. The company declined to comment.

“The highest priority is to get to zero incidents,” said Carl Weimer, executive director of the nonprofit Pipeline Safety Trust, a watchdog group founded after a 1999 gasoline pipeline explosion in Bellingham, Washington, that killed two children, both 10, and an 18-year-old.

Congress isn’t likely to move to repeal or rewrite the Obama rule until a new head of the PMSHA is in office. But the chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, Pennsylvania Republican Bill Shuster, said last week that easing up on the regulations was the right thing to do.

“Are there some bad actors out there? Sure,” he told the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners. “But we gotta let these industries go do their business.”