A few weeks ago, a young man stepped through the doors of a substance abuse treatment center in Midland, and spotted our cameras and notepads.

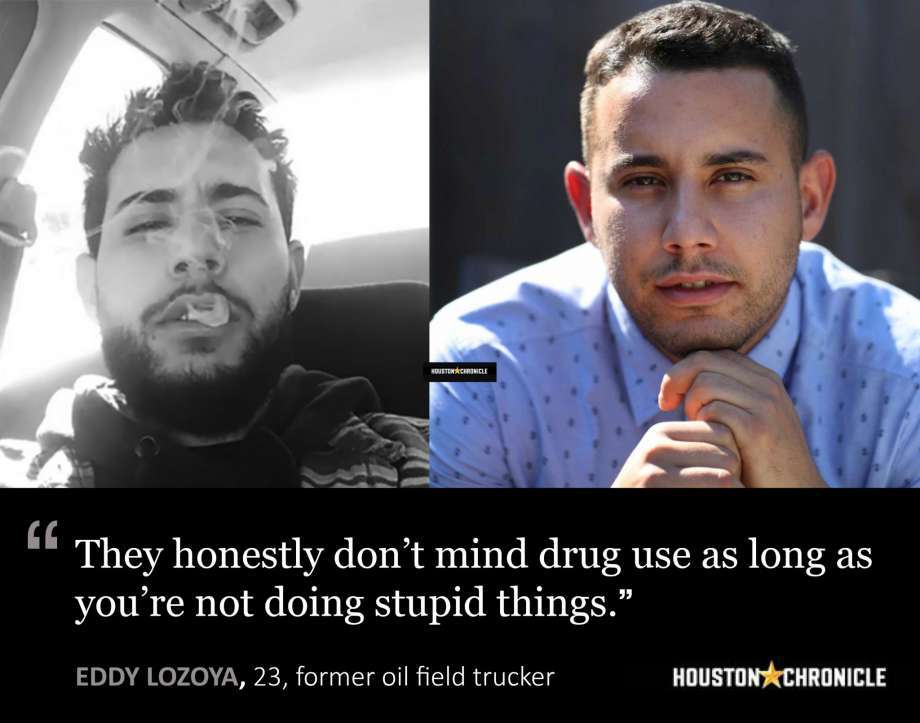

Eddy Lozoya had come early for a treatment session, knowing a photographer and reporter would be there to interview recovering drug addicts who had worked for oil companies. He wasn’t on our schedule, but he wanted to tell his story.

He leaned forward, intent on getting our attention, and told us how drugs took control of his life as he earned $2,000 a week in the oil patch. He would often drive 36 hours straight, hauling sand and water in a semi-truck across the Permian Basin, fueled by cocaine and motivated by a boss who berated him and his fellow truckers to stay on the road as long as they could. Eventually, he turned to oxycodone, a highly addictive opioid pain medication.

“You’re in so much pain,” he said at a sober living home in Midland, where he is recovering from years of addiction. “There’d be days I couldn’t get out of bed. I’d already have a couple lines lined up, just planning for the day ahead.”

That wasn’t really the story I had set out to write. A month earlier, a drilling executive had told me that more job applicants were failing drug tests. I thought I would write a straightforward business story about how an increase in drug abuse had slowed hiring in the oil industry. Then, in Midland, I spoke to the people who had come out of the oil patch addicted.

“A lot of people out there,” Lozoya said, “are using drugs.”

Houston Chronicle photographer Steve Gonzales and I found recovering addicts willing – even eager – to share their stories. In each case, they described a cycle of addiction spurred by long work hours, large paychecks and the constant shift between extreme boredom in remote West Texas and high stress in the oil patch. Breaking that cycle required luck, will power and support, whether in a treatment center or the back of a police car.

Eight years ago, Cody Watson found himself in the latter, after he was pulled over for making a rolling stop. He was using drugs on the job, and still had some in his pocket. He called his employer from jail, thinking he could keep his job as an oil field electrician. He didn’t.

“I was in such a hurry to get the job done so I could get my next fix,” he said. “I was working with 14,000 volts of electricity. I was putting other people’s lives in my hands.”

He spent a few months in a substance abuse felony treatment program, and 90 days at a halfway house. He got involved with Alcoholics Anonymous and has stayed sober.

Sobriety didn’t come easy for Kevin Tyson. For years, the oil field specialist would cook meth, sell it and shoot it. His schedule on a drilling rig – seven days on, seven days off – allowed for his double life.

Tyson quit for awhile, and scored a prestigious job with a major oil company. But boredom set in. He lost his job after three DWI charges and went back to cooking meth. He ended up in a hospital – twice – before finally turning his life around in 2001.

Tyson knew oil field workers who didn’t survive those wooly years and others who ended up in mental institutions. “They’ll never come back,” he said.

Some do. Lozoya, the former trucker, found his way back — in rehab.

“My life was so unmanageable,” he said. “Rehab gave me so many tools to live. It just made me realize how powerful your mind is. You’re in control of your life.”

This article first appeared on the Houston Chronicle – an Energy Voice content partner. For more click here.

Recommended for you