The frantic shale race may be causing some long-term damage to assets in the Permian and other major U.S. oil fields.

As production from wells rapidly declines, drillers are rushing to add new ones at a faster pace in order to keep increasing output. The problem is that drilling multiple wells closer together is contributing to the drop in established ones, and sometimes causing harm that can’t be fixed.

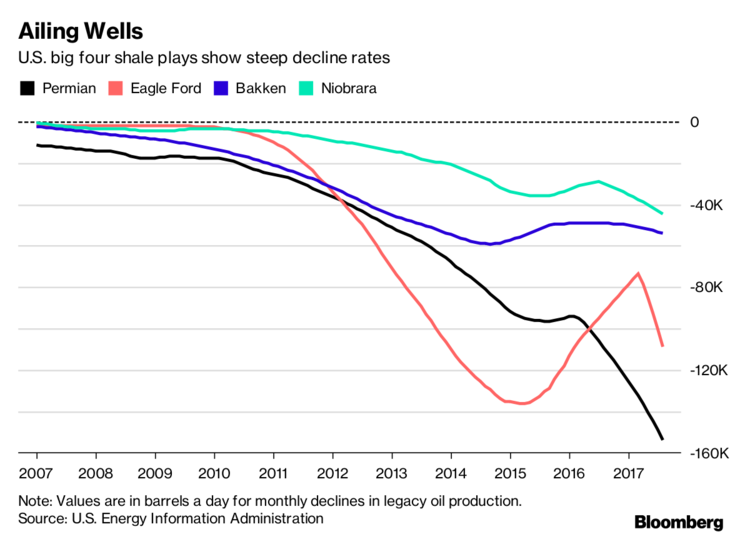

Output from legacy wells — a term that in the fast-pace shale world includes those that are just a month old — is dropping by 350,000 barrels a day and has fallen steeply since 2012, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Unlike offshore wells in the Gulf of Mexico, which can produce for decades, shale wells can peak within months and sometimes cease after two years. Eager explorers may undercut the life of wells by over-drilling, said Russell Clark, investment manager at Horseman Capital Management Ltd. So-called frack hits occur when drilling in one well interferes with another, causing a pressure transfer that can disrupt or stop production.

“New well production is increasingly cannibalizing legacy production,” Clark wrote in a report. “The decline rate looks to be accelerating.”

It’s a trend particularly acute in the prolific Permian basin in West Texas and New Mexico.

Companies such as ConocoPhillips say it’s up to producers to give wells drilled in the area their best chance to succeed.

“You can drill too fast in these unconventional plays,” said Alan Hirshberg, executive vice president of production drilling at ConocoPhillips, in a conference call last week. “We get ultimately much better recoveries and avoid causing damage to an area that you can’t go back and fix very easily.”

The oil downturn has forced producers to find creative solutions to keep drilling in a world of lower prices. Some of those cost-cutting strategies, such as packing wells more densely and closer together, are now causing major headaches.

Another risk from the boom is that shale producers have been spending more than they make for a decade, aided by a flow of money from investors. But that has encouraged companies to focus on ramping up production at the expense of profitability, according to a report released last week by Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

That could worsen a global supply glut and push down oil prices, leading to an outflow of finance that may jeopardize the entire industry.

“At some point debt investors start to worry they will not get their capital back and cut lending to the industry,” Clark said. “Even a small reduction in capital would likely lead to a steep fall in U.S. production.”