Hurricane Florence continues to intensify rapidly as it moves ever closer to the U.S. Atlantic coast, where it could strike somewhere between South Carolina and Virginia late this week.

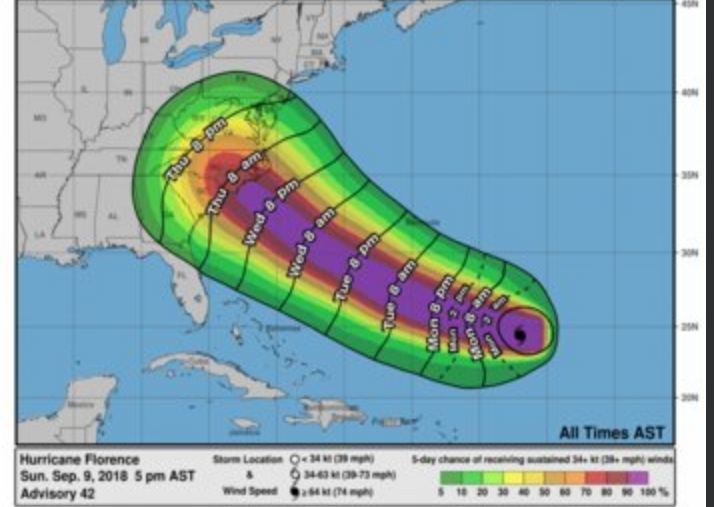

Florence was about 720 miles (1,160 kilometers) southeast of Bermuda, with maximum sustained winds of 85 miles per hour, making it a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale, the National Hurricane Center said in an advisory at 5 p.m. New York time. The storm was moving toward the west at about 7 mph and is expected to speed up and turn toward the northwest by Monday.

“Florence is forecast to rapidly strengthen to a major hurricane by Monday, and is expected to remain an extremely dangerous major hurricane through Thursday,” the center said. Models show the storm reaching Category 4 intensity within 48 hours, with winds of 130 mph to 156 mph, hurricane specialist Eric Blake said in a forecast discussion.

South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster on Saturday declared a state of emergency in anticipation of the storm. The move will allow the state to use the National Guard for preparations and recovery if necessary. North Carolina and Virginia have taken similar steps.

Most forecast models point to Florence’s eye hitting the southeast coast sometime on Sept. 14, said Anthony Chipriano, a meteorologist at Radiant Solutions in Gaithersburg, Maryland. What’s worrisome is that the storm could stall at that point and wring out heavy, flooding rains throughout the area.

The northern coast of South Carolina and the Outer Banks of North Carolina are likely to be the areas most impacted by the storm, which could cause $15.32 billion in damage if it stays on its current five-day forecast track, said Chuck Watson, a disaster researcher at Enki Research in Savannah, Georgia.

A storm would normally weaken considerably if it stalled on the coast, by choking off its own energy supply as it churned over its own wake, Watson said. But the Gulf Stream is pushing warm water past Cape Hatteras, which could create a “nightmare scenario” that could lead to as much as $25 billion in damages, putting Florence in the top 10 of the most destructive storms, he said.

Hurricane track and intensity forecasts often have wide margins of error beyond five days, and with Florence computer models have struggled to accurately predict what the storm will do.

“The models have not been very good with intensity for this system pretty much for the entirety of the storm,” Chipriano said.

Bermuda High

More than 3.9 million homes that would cost more than a $1 trillion to rebuild are at risk from hurricanes on the U.S. Atlantic coast from Maine to Florida, according to CoreLogic, a property analytics firm in Irvine, California.

The East Coast’s fate from the current storm will be decided by a weather pattern called the Bermuda High. A semi-permanent feature in the Atlantic, the high rotates in a clockwise manner and will steer Florence through the ocean.

Nine storms have emerged across the Atlantic so far this year. To the east of Florence, forecasters are also watching tropical storms Helene and Isaac. Helene is brushing past the Cabo Verde Islands off Africa before drifting into the central Atlantic, while Isaac could grow to a hurricane and threaten the small islands in the Caribbean Sea by Thursday.

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, Hurricane Olivia, forecast to weaken to a tropical storm, may hit Hawaii as soon as Tuesday. Further west, Typhoon Mangkhut will sweep past the U.S. territory of Guam Monday and Tuesday.

Recommended for you