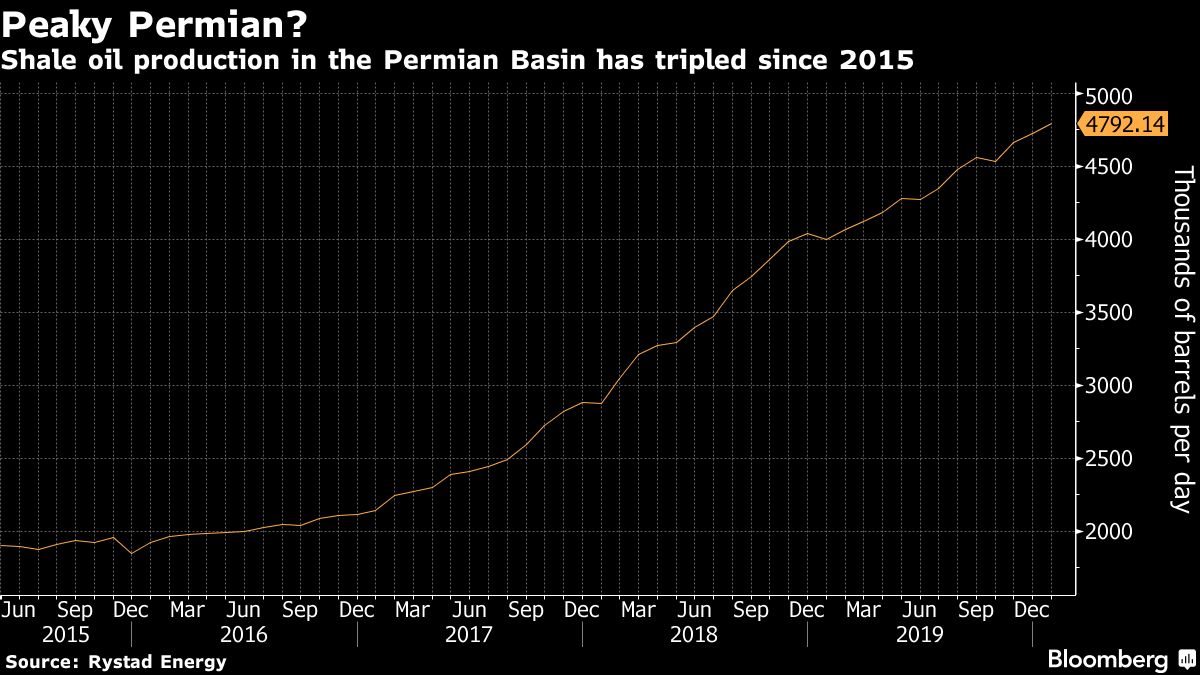

Such is the extent of the shakeout in the U.S. shale industry that Permian Basin oil production is closer to peaking than many forecasts suggest, according to one energy investor.

Adam Waterous, who runs Waterous Energy Fund, regards the sector’s financial position as unsustainable after years of disappointing returns for investors and negative free cash flow. With capital markets now largely shunning shale producers, the impact will begin to show in oil and natural gas output from the largest U.S. oil patch, he said.

“We think we are at or near peak Permian” production, Waterous said last week in an interview. “The North American oil market has been grossly overcapitalized, which is not sustainable.”

Predicting peak Permian output for 2020 isn’t a mainstream view. There’s plenty of debate about how much production growth in the West Texas and New Mexico patch may slow this year as shale drillers slash capital spending, but the consensus is that supplies will rise, albeit at a slower pace. Tai Liu, an analyst at BloombergNEF, said in a report Tuesday that the pessimism may be overdone. Such considerations have global ramifications, as the U.S. is expected to account for a large portion of worldwide supply growth this year.

“The capital gains model is broken,” he said. “The M&A market is gone and it’s not coming back.”

The kind of industry rationalization Waterous describes may work to his advantage. His Calgary-based private equity firm, which he founded in 2017, controls two Canadian oil producers. One of them, Cona Resources Ltd., agreed to buy Pengrowth Energy Corp. in November for C$28 million ($21 million) after Pengrowth’s share price cratered as the company buckled under a huge debt load. Waterous Energy is looking for more assets in Canada and the U.S.

Waterous likens the plight of U.S. shale in recent years to the five stages of grief. The first stage, denial, is characterized by a belief that the M&A market will return, he said. That’s followed by anger (“the market is wrong”), then bargaining, by trying to operate within cash flow, followed by depression — moving to the free cash-flow model that many shale operators have been touting.

The final stage, acceptance, is defined by Waterous as the industry finally resolving to provide investors with cash payouts via dividends so that they recover their initial investments.

Over the past five years, the industry and its investors “mistook a massive structural change for a simple cyclical event,” he said. “It’s impossible to continue to have uneconomic production and capex.”