Decommissioning Southeast Asia’s aging oilfields offers a vast but challenging market opportunity.

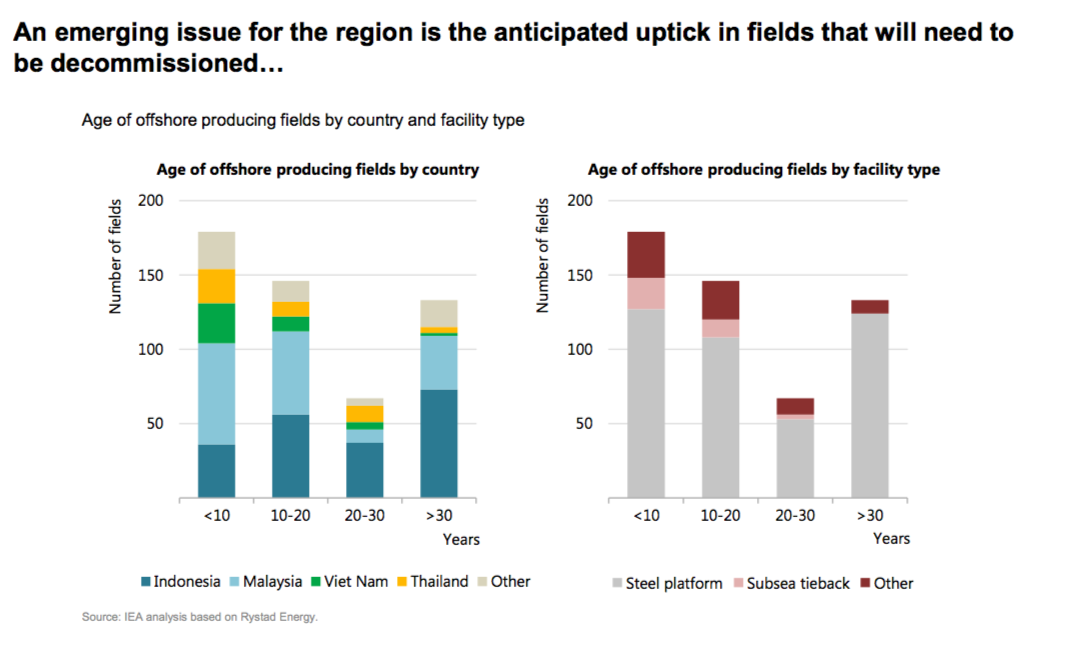

More than 200 offshore fields are expected to stop producing in Southeast Asia by 2030 with total decommissioning costs estimated to range from $30 billion to as much as $100 billion.

Indeed, the potential market opportunity in Southeast Asia could be huge with more than 1500 platforms and over 7000 wells projected to need decommissioning by 2030.

Significantly, the decommissioning industry in the region will evolve differently from the rest of the world given the vast number of relatively small structures and wells. As a result, the region will need to develop its own specialised industry, which does not yet exist, Philip Whittaker, a partner specialising in oil and gas at Boston Consulting Group, told Energy Voice. The biggest opportunities will be in Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, all home to large national oil companies (NOCs) together with leading international companies, added Whittaker.

While decommissioning activities have started on a small scale, mainly in Thailand, the complexity level is expected to rise as the types of projects being permanently shut down are set to expand across the region. So far, most decommissioning projects have involved steel platforms in shallow water, but in future more complex structures will need to be dismantled in deeper waters.

Adding to the complexity, decommissioning liability is a big unknown that is just starting to be recognised by host governments. Unlike in Western regimes such as in the Gulf of Mexico and the North Sea, where abandonment provisions are already in place so the last operator holding the asset does not have to pay all the decommissioning costs, the rules in Southeast Asia are much less developed.

Legal and regulatory frameworks governing decommissioning are far from certain in most jurisdictions. Even in Thailand, which has made the most progress on decommissioning laws, there remains a lack of clarity around provisions for abandonment. A dispute between Chevron and the Thai government over the cost of decommissioning the giant Erawan field underscores the risks for operators in the region as assets near the end of their lives.

The dispute stems from a 2016 law that requires operators to pay the costs of decommissioning assets they installed even if they no longer operate them. In June, Chevron objected to a request by Thailand’s energy ministry to start paying decommissioning costs – estimated at $2 billion – for the Erawan field. The amount also covers still usable assets that Chevron will transfer free of charge to state-backed PTT Exploration & Production (PTTEP) when it takes over the field in April 2022. The US major argues that under the terms of its contract it was liable only for infrastructure deemed no longer usable. The pair aim to find a resolution to the disagreement by March 2021, which if successful, should help set a precedent for the decommissioning sector in Thailand, and perhaps the wider region.

Unlike Thailand, which operates a concessionary contract regime, the most prolific producers, Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam, mostly use production-sharing contracts (PSCs). These were largely based on the assumption that IOCs would hand over their fields and assets to the NOCs when the PSCs expired. Officials drafting the rules for the legacy PSCs over 25 years ago never conceived that oilfields could be liabilities rather than assets.

As a result some old fields, with massive decommissioning liabilities, have already been transferred from IOC to NOC, so that the NOCs can extract the last barrels from the mature fields, seemingly oblivious to the liabilities associated with safely decommissioning them.

Indonesia’s Pertamina, Malaysia’s Petronas and Vietnam’s PetroVietnam, look set to be left managing much of the abandonment in Southeast Asia. In recent years, the issue of decommissioning has gained increasing recognition as legacy PSCs have begun to expire and transferred to the state-owned companies. Although financial provisions have started to be made by the NOCs, it is unclear if these will be adequate or whether the governments will reallocate the funds for other uses before decommissioning starts.

Significantly, the decommissioning sector faces numerous challenges, including a lack of understanding about the cost and scope of decommissioning needed, uncertainty surrounding financial readiness, as well as the lack of skilled contractors in the region, Eugene Chiam, a Singapore-based upstream specialist at consultancy Rystad Energy told Energy Voice.

Whilst the opportunities for the international service sector are potentially enormous it is difficult to envisage that these opportunities can be realised until regulatory frameworks are in place that enable appropriate finance to be made available, Peter Godfrey, managing director Asia Pacific at The Energy Institute, told Energy Voice.

“Given the fact that stakeholders remain reticent to accept liability or even, in many instances, shared liability, for decommissioning activity, that could enable progressive discussion to take place, I suspect that it will take many years or even a few disasters before the whole issue is given the weight it deserves,” added Godfrey.

Nevertheless, numerous steel facilities and wells will need to be decommissioned or at least made safe in the future. This offers opportunities for both the local and international service sector to engage with the NOCs to help find solutions.

Crucially, it is important that all Southeast Asian countries ensure they have a clear unambiguous decommissioning regime in place as soon as possible. But as energy research firm Wood Mackenzie notes, “it would be more efficient to adopt guidelines and processes already in place in the UK or Gulf of Mexico, rather than reinventing the wheel”.