ExxonMobil is exploring opportunities to invest in LNG-to-power projects in Vietnam as the country faces chronic electricity shortages and Hanoi welcomes US companies to fix a trade imbalance.

In an effort to solve the looming power crisis the government is rapidly building solar power capacity and hopes to start importing LNG by 2022 to fuel gas-fired power plants.

The government said in a statement that ExxonMobil wants to explore investment opportunities in Vietnam’s energy sector, particularly LNG import facilities and gas-fired power plants. It issued the statement after a phone call between Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc and Irtiza Sayyed, President of ExxonMobil LNG Market Development, in mid-June.

“With ExxonMobil expected to expand its LNG supply business via major investments in Mozambique, Qatar and Papua New Guinea, it stands to reason that the company would look to develop new demand markets via LNG-to-power projects,” Andrew Harwood, Asia Pacific research director at Wood Mackenzie, told Energy Voice.

Indeed, the government said that the US giant could invest in a proposed 4GW LNG-to-power scheme in the northern port city of Haiphong, which could start operating sometime between 2025 and 2030.

ExxonMobil could also invest in a 3GW LNG-to-power scheme in the Mekong Delta province of Long An, added the government.

The supermajor would use LNG imported from the US or elsewhere in its global portfolio, however importing LNG from the US will help balance trade between the two countries.

Delta Offshore Energy and Energy Capital Vietnam have also proposed LNG-to-power schemes in Vietnam. Both operators have US shareholders, are proposing US LNG suppliers and are courting US finance.

Significantly, US pressure on Vietnam to cut the trade imbalance between the two countries offers American LNG players a unique opportunity to tap the emerging market. The proposed LNG-to-power projects will help bolster US-Vietnam trade relations, with tens of billions of dollars in US export content expected over the 20-plus year life of the plants. In particular, the supply of US LNG and equipment – as well as various services from US partners, such as turbine supplier GE – will help balance Vietnam’s trade surplus with the US.

More gas and LNG will be needed as plans for coal-fired power have stalled. As responsibility for power generation has been devolved in Vietnam, local authorities have started reversing decisions made by Hanoi that favoured coal-fired power. This underscores a push from local governments – particularly in electricity-short southern Vietnam – for cleaner energy options such as gas and renewables instead of coal.

With the economy expanding at a rate of around 6-7% per year, Vietnam expects power generation will hit 125 to 130 GW by 2030, up from 54 GW capacity now. In 2019, 33% of the country’s power mix was fuelled by gas with the remainder supplied by renewables and coal.

However, as upstream production expectations continue to disappoint, Vietnam will need to increasingly import LNG.

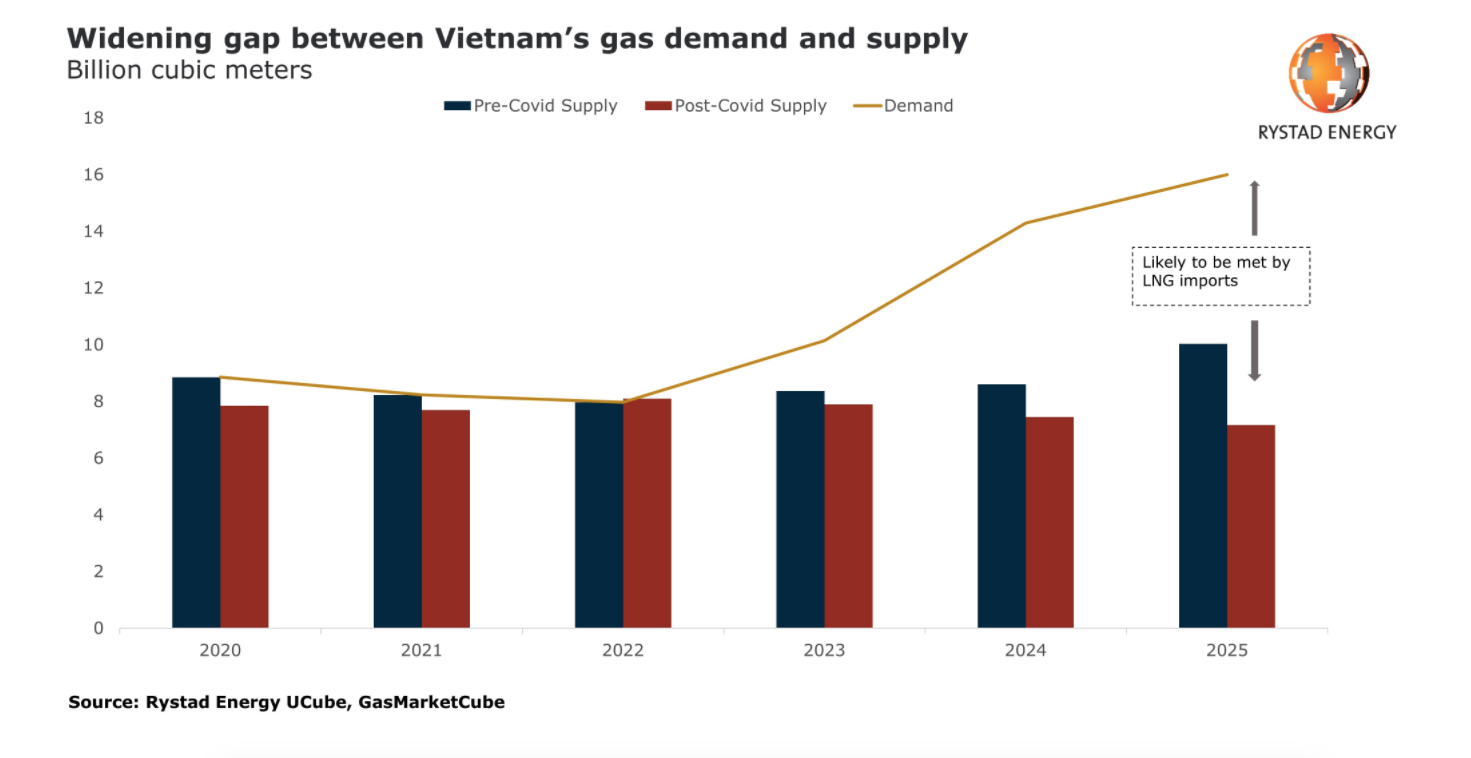

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Rystad Energy projected that Vietnam’s domestic gas output would hit 10 billion cubic metres (cm) by 2025. Of this, about 60% of total gas produced was expected to come from new developments. The research company’s updated outlook shows a much different picture, with the pandemic crisis and low oil prices postponing more than 200 billion cm of Vietnam’s undeveloped gas resources.

As a result, Vietnam will only produce 7 billion cm of gas in 2025, rather than the projected 10 billion cm, creating a 9 billion cm gap between domestic production and the 16 billion cm of expected gas demand.

To avoid reverting back to heavy coal imports to feed power generation, Vietnam will likely start importing LNG as early as 2022, reported Rystad. Even so, importing sufficient LNG volumes will be difficult.

There are currently four LNG terminals in the project pipeline – Thi Vai LNG, Son My LNG, Tien Giang LNG Projects, and South West LNG – which together will have a combined capacity of 10 millon tonnes per year (mtpy) by 2025. However, the terminals, which are being built primarily in southern Vietnam, will only reach 1 mtpy import capacity by 2023 with the start-up of Phase 1 of the Thi Vai terminal. This will only marginally fulfil the demand-supply gap, predicts Rystad.

Indeed, Vietnam is projected to start suffering blackouts as early as this year. The situation is expected to get progressively worse until around 2022-2023 because of a shortage of investment amid surging power demand, Tran Tuan Anh, the Vietnamese minister of industry and trade, warned the National Assembly last November.

No doubt the looming power supply crunch will harm its expanding manufacturing sector if it goes unaddressed. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that Hanoi is courting potentially big investors, such as ExxonMobil.