A pair of oil and gas fields controlled by Japanese companies offshore Vietnam could become a potential flash point in the disputed waters of the South China Sea as Beijing continually seeks to aggressively assert its claims.

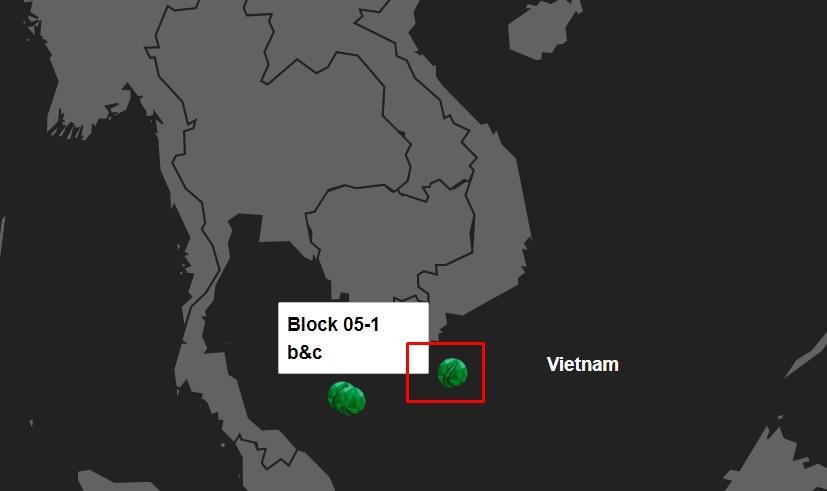

Japan’s Idemitsu and Inpex, in partnership with Vietnam’s national oil company, PetroVietnam, operate the two fields, Sao Vang and Dai Nguyet. The fields, in Block 05-01, straddle China’s sweeping claim to most of the South China Sea via its U-shaped ‘nine-dash line’, which is not recognised by its neighbors or internationally by The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

China’s increasing harassment of Vietnamese upstream developments in disputed areas of the South China Sea has seen numerous projects abandoned in recent years. And fears that Beijing will try to derail the Block 05-01 development are believed to have trigged the aborted sale of part of the project to Singapore-based Jadestone Energy. Having an all-Japanese arrangement will make it easier for Vietnam and Japan to coordinate a response to any Chinese harassment, sources told Energy Voice.

Inpex, which holds a share of the block through its subsidiary Teikoku Oil, reneged on its deal to sell Jadestone a 30% equity stake for $14.3 million, agreed in 2016. Jadestone contested the deal’s termination, which eventually saw the London-listed company initiate arbitration proceedings starting early July 2020. On 11 November 2020, a full and final settlement to the dispute over the failed acquisition was agreed.

It is likely that Inpex’s decision to cancel its deal with Jadestone was prompted by an unofficial request from the Vietnamese government. Indeed, it makes sense that Hanoi would prefer partners from nations that share strategic interests with Vietnam in resisting China’s aggression in the South China Sea.

“There is some speculation that the consortium, at the behest of the Japanese government, wants to keep the block as an all-Japanese arrangement to manage any threats from China that might prevent development of the fields in the future,” Bill Hayton, an expert on the geopolitics of the South China Sea at UK-based thinktank Chatham House, wrote in an article for The Diplomat.

The fields lie in shallow waters close to the Nam Con Son gas transportation pipeline and existing production facilities. They also have approved field development plans, which marks a rare achievement in Vietnam, where the arduous approvals process and bureaucracy have stalled many other potential developments. With new upstream production tantalizingly close, Vietnam will be keen to see the field development progressed in a timely manner without Beijing’s interference. Aside from helping to meet surging domestic energy demand to feed a rapidly expanding economy, Hanoi will also be desperate for upstream development success to help lure back investors that have fled in the wake of China’s bullying tactics in recent years.

Still, “China will definitely try to pressure Vietnam not to go ahead with the development,” Hayton told Energy Voice. Although, he would be surprised if Beijing tried to pressure the Japanese companies directly.

Indeed, it will be significant if Japan Inc, an informally close relationship between the Japanese government and the private sector, can move forward with the development of Block 05-01 and offer a counterbalance to Chinese pressure.

“I am sure if you are Vietnamese that you would much rather have Tokyo behind you, rather than a private Singaporean company, that would certainly not accept much heat from China,” Greg Poling, director of the Washington-based Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI), told Energy Voice.

Moreover, the Japanese, like the U.S., are concerned about Beijing resorting to various coercive tactics in the South China Sea to force rival claimants to accept China as the only viable partner for jointly developing natural resources.

The U.S. has very openly raised concerns about China’s actions in the South China Sea, reiterating that Washington regards Beijing’s expansive maritime claims in the waters as unlawful according to a 2016 international tribunal ruling. As a result, the U.S. has expanded its military presence in the contested waters this year in an attempt to push back against China.

Although the Japanese have been much more subtle, their position is similar to the Americans, Collin Koh Swee Lean, research fellow at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, told Energy Voice.

“In any case, there is not just interest on the part of the Japanese, but there is demand on the Vietnamese side too,” said Koh, who added that the Vietnamese have been spooked by past incidents, including Chinese harassment of Repsol in 2018, that eventually saw the Spanish company exit Vietnam. Reports suggest that Vietnam agreed to pay around $1 billion to Repsol and its partner UAE-based Mubadala in termination and compensation arrangements after Hanoi cancelled their South China Sea operations following pressure from Beijing.

Aside from the Repsol case, there have been various other incidents where Beijing made explicit or implicit threats against Hanoi’s energy ventures with external companies. This has a debilitating effect in discouraging participation from the oil and gas sector, especially given the security risks to companies and political risks to the parent companies involved, said Koh.

“That is why I would not be surprised that the Japanese are doing this to manage the threat from China, and with Vietnam’s support,” he added.

“The Chinese will most likely make advances behind the scenes to try to persuade the Japanese to let go of this project, and when this fails, they will try to intimidate through militarized coercive actions,” said Koh.

Similar action was seen earlier this year when the Chinese harassed the West Capella drilling rig under contract to Petronas off Malaysia.

© Supplied by Jadestone Energy

© Supplied by Jadestone Energy