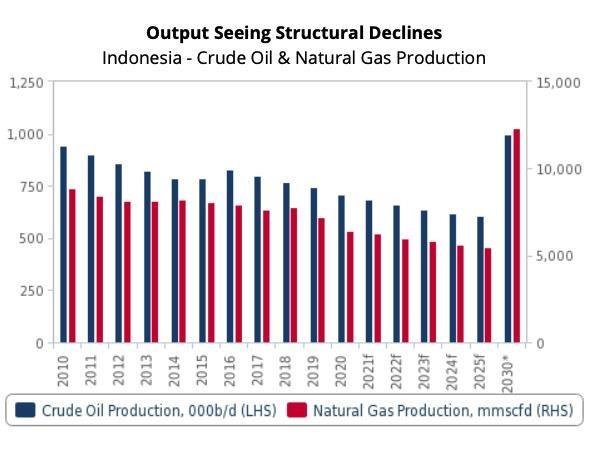

Indonesia’s crude oil and natural gas production growth outlook continues to be downbeat. Total oil and gas output have seen broad declines since 2010 and the long-observed trend is not expected to be reversed any time soon, reports Fitch Solutions.

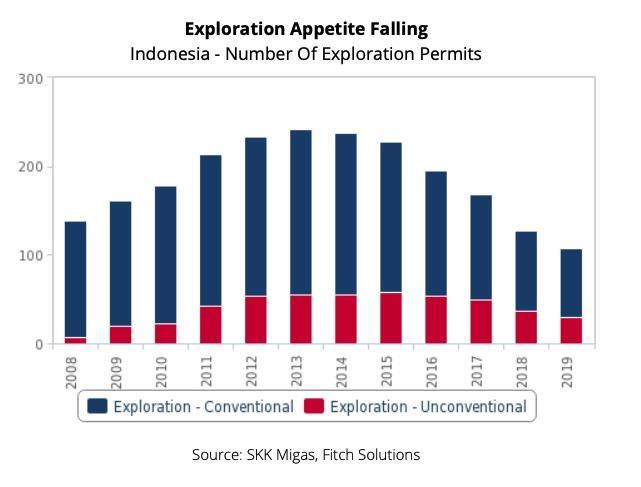

Both are due to see extended annual declines through to the end of our forecast period in 2030, a sharp contrast to ambitious state targets for both to make gains of more than 40% and 90% by 2030, from 2020 levels. The main drivers behind these declines have been the maturing of existing assets and a slowdown in capital spending in the upstream sector. Exploration has not been able to keep pace with natural declines and as a result, despite touted strong below ground potential, new discoveries and their conversion to commercial projects have been few next to high regulatory and funding challenges.

Indonesia’s upstream projects pipeline as per state regulator SKK Migas includes four ‘national strategic’ projects for both oil and gas. Though how many of these would come online in the current timeline and whether they would reach full potential and be sufficient to reverse the overall structural downtrend in production remains to be seen. All four projects have already seen deadlines delayed due to operational and financial challenges that have been compounded by the Covid-19 pandemic, while planned exits by major IOC partners further complicate the outlooks for Indonesia Deepwater Development (IDD) and Abadi LNG.

‘Indonesia Petroleum Bid Round 2021’ launched in June 2021 including six exploration blocks does provide some upside. For three of the six blocks – Merangin, North Kangean and Sumbagsel – bidders are able to choose between the newer gross split production sharing contract (PSC) regime and the older cost-recovery scheme, which Indonesia had tried to phase out earlier amidst lukewarm industry reception. Flexible licensing terms next to higher contractor shares have been included in order to attract investor interest with more blocks due to be offered in subsequent rounds, but the industry’s reaction to the round remains difficult to gauge at this point, as public expressions of interest have been few and far between.

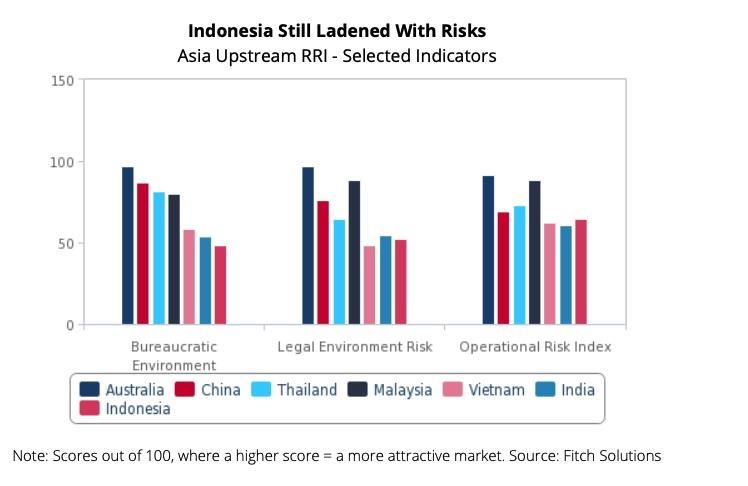

Indonesia’s regulatory environment continues to be among the most complex in the region and remains a stumbling block for many investors. Of the seven largest oil and gas producing markets in Asia, Indonesia’s score for the ‘bureaucratic environment’ metric as per the Fitch Solutions Upstream Risk/Rewards Index (RRI) far underperforms the others, while its scores for ‘legal environmental risk’ are also among the lowest, while also trailing the regional average. The recent improvements made in the sector, mostly aimed at easing administrative steps, streamlining processes and strengthening contractor benefits, have done little to excite investors who have become more selective and risk-averse. A case in point here is the long-run saga of the Masela PSC containing the Abadi gas field. The project has encountered numerous delays since its initial inception in 2010 and despite government approval for its revised development plan having been finally secured in 2019, FID again has been pushed back as lead developer Inpex grapples with Covid-19-related difficulties.

Indonesia’s 2021 ‘Omnibus Law’ designed to spur investments into a number of key sectors including oil and gas simplifies the steps needed for both domestic and foreign companies to engage in downstream activities, but in contrast, does little to ease similar complexities in the upstream. Instead, the law adds on a new requirement for upstream PSC holders to obtain a business license from the ‘central government’ – comprising of the president, the vice president and the minister of energy and mineral resources – prior to being able to engage in upstream activities. The law also does not stipulate the specific criteria needed for PSC contractors to obtain these licenses, while also being unclear about how existing PSC holders will be affected.

Pervasive resource nationalism in the sector also would do little to appeal to potential investors more so amid growing interest in decarbonisation, energy transition initiatives. While on the one hand Indonesia has sought to rekindle interest in its declining upstream sector, on the other, it has abided by the habit of allowing Pertamina and its subsidiaries take over mature oil and gas blocks from the hands of the IOCs, invoking concerns about resource nationalism and reduced market competition.

The passing on of mature assets to SOEs also brings with it concerns about their capacities to maintain output. This has been the case for the Mahakam block, where both investment and output are believed to have nearly halved since operatorship passed onto Pertamina from TotalEnergies (then Total) in 2018. Pertamina is due to take on a further 11 expiring blocks from IOC operators in 2021. In August, it became operator for the Rokan oil block, Indonesia’s second largest, in the place of Chevron, whose request to extend control of the block was refused by the Indonesian government.

High above-ground risks will continue to deter investors from looking favourably towards the Indonesian upstream, especially as investments into traditional fossil fuel projects come under increasing public and shareholder scrutiny amidst growing emphasis on decarbonisation and the transition away from pollution-heavy energy sources such as oil. Even Pertamina itself appears to be gradually reorienting investment priorities towards the downstream and low carbon initiatives, allocating some 54% of its budgeted capex for its refining, petrochemicals, renewables and new energies business in 2021, the highest on record, which compounds our bearish long-term outlooks for crude oil and natural gas production in Indonesia.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Fitch Solutions

© Supplied by Fitch Solutions © Supplied by Fitch Solutions

© Supplied by Fitch Solutions © Supplied by Fitch

© Supplied by Fitch