Natural declines and underinvestment in new exploration has left Philippine oil and gas production in freefall posing significant risks to future energy security. The risk is particularly acute given how reliant the Southeast Asian nation is on oil and gas for power generation, industrial processes and transportation, warn analysts at Fitch Solutions. But interest from investors has been rekindled.

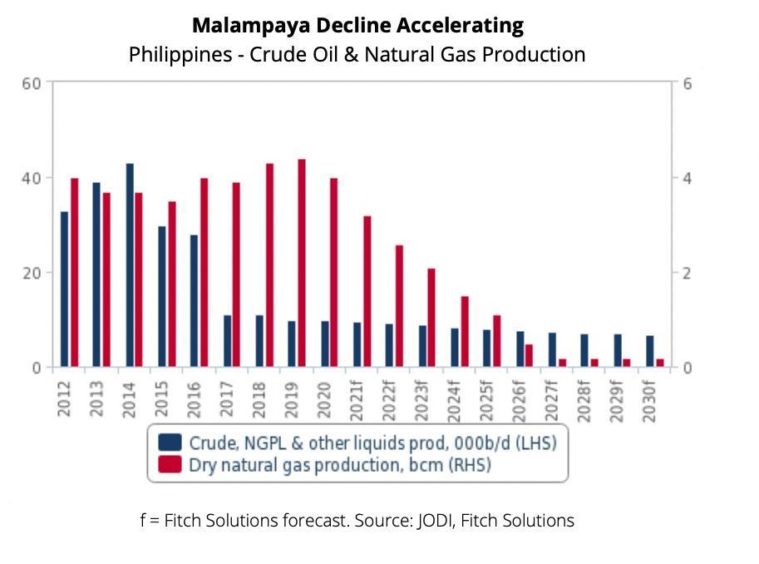

Production has been broadly falling since the early 2010s with a lack of significant new finds and accelerating declines at Malampaya, the country’s biggest gas and condensate field. New operator Udenna Corporation, which took over Malampaya from Shell earlier this year, confirmed in July that the field could face a gas shortfall from as soon as 2022. This bearish assessment was echoed by the Philippines Senate Committee on Energy, which affirmed that Malampaya’s output was already in a “depletion stage” despite earlier estimates that the gas could last until 2027.

“Efforts to spur exploration and discover tie-back opportunities to the mature (Malampaya) field have not panned out either due to disappointing drilling results from deeper offshore areas and geological barriers associated with onshore petroleum exploration. In addition, offshore exploration also faces stringent opposition from China which lay claims over almost the entirety of the South China Sea, known as the West Philippines Sea in the Philippines where many of the Philippines’ remaining under-explored petroleum blocks are situated,” Fitch Solutions Country Risk and Industry Research said in its latest report.

Indeed, companies have been reluctant to invest in the area due to the heightened tensions and uncertainties.

Still, the Philippines lifted its long-time ban on oil and gas exploration in the disputed waters in October 2020, ahead of the impending depletion of oil and gas reserves at the country’s sole producing field Malampaya. “The need to ensure continuous supply of indigenous resources trumped efforts to deescalate tension,” said Fitch.

Significant Energy Security Risks

“The situation is highly problematic for the Philippines, given that Malampaya remains its only significant source of oil and gas and supplies, with the field providing 30% of the main island of Luzon’s electricity needs, or about 20% of the Philippine’s total electricity requirements,” reported Fitch.

“The gradual reduction in gas production from the field is already driving up consumer electricity costs and causing rotational power outages across the islands; a complete stoppage without replacements in place would prove to be highly damaging for businesses and end-users alike,” warned Fitch.

The looming risk of the loss in Malampaya gas has also spurred liquefied natural gas (LNG) import infrastructure developments across the Philippines. The number of LNG projects that have been awarded a notice to proceed from the Department of Energy (DOE) has now increased to seven, each targeting start-ups by the mid-2020s ahead of the forecast depletion of Malampaya. However, many face delay risks, not least due to difficulties caused by Covid-19 infections, but also due to legal processes, regulatory regimes, insufficient associated infrastructure in place and rising competition from renewables, cautioned Fitch.

What’s Next?

“In spite of the dire situation at hand, there has been no new exploration announced in the Philippines after the lifting of the long-term ban on oil and gas exploration. However, there appear to be a growing number of firms keen to rekindle interest in the Philippines despite lingering regulatory and maritime uncertainties” reckons Fitch.

For instance, in July, Energy Secretary Alfonso Cusi confirmed that the DOE has endorsed the awarding of three new service contracts (SCs) – although he did not reveal further specific details – that are now pending review by the Office of the President.

PXP Energy subsidiary Forum Energy also expressed interest in resuming drilling works at its suspended SC-72 offshore Reed Bank, even without a partner. Australia’s Sacgasco has also acquired Nido Petroleum and its four offshore production sharing contracts from parent firm Bangchak Petroleum and plans to evaluate resources in the license areas with a view towards realising early production.

More clarity on the situation, particularly with regards to China’s stance towards drilling in the disputed waters, will still be needed before more firms can farm in.

However, “as a prospective market to target for investors the Philippines is highly interesting given the large, energy hungry domestic market and ample trade opportunities throughout to the region. Although for now most seem content to wait it out for maritime tensions to dissipate and below ground potential to become more concrete,” said Fitch.

A joint exploration with China’s CNOOC still cannot be ruled out even though negotiations have not resulted in commercial activities since the signing of a memorandum of understanding (MoU) in 2018.

“The Philippines DOE has maintained that any oil and gas activities offshore would need to follow the 60:40 Filipino-foreign ownership requirement as stated in the 1987 Philippines Constitution, although it remains unclear how receptive CNOOC or Beijing would be to this given vast maritime claims,” added Fitch.