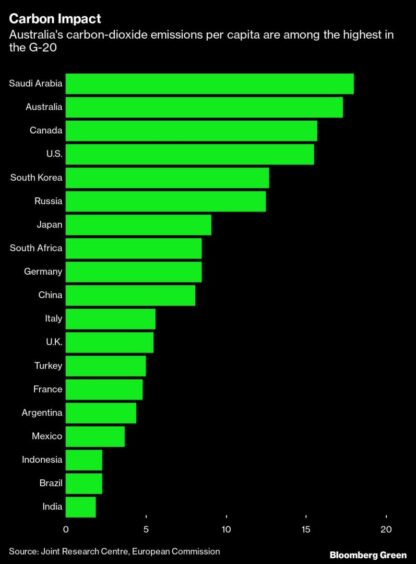

Australia, one of the world’s top per-capita polluters, finally agreed to a plan to zero out its carbon emissions by 2050 but fell short of committing to harder short-term targets demanded by climate activists.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced the target days before he is scheduled to head to Europe for G-20 talks and then the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow. It follows a new round of fractious domestic debate on climate policy, an issue that’s riven Australia’s politics for more than a decade and comes after pressure from allies including the US on Australia to show more urgency in action to limit global warming.

Wood Mackenzie Asia Pacific Head of Markets and Transitions, Prakash Sharma, said that “Australia’s desire to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 is a step in the right direction. The country’s major trading partners – China, Japan, and South Korea – are already in transition towards that goal. Other major energy exporters such as Russia and Saudi Arabia also announced net zero goals by 2060 in recent weeks. This means Australia will need to retool its commodity exports industry to align with the Paris climate targets.”

“Our analysis shows that Australia can reach net zero emissions by 2050. Although the pathway requires complete transformation of its traditional energy and export sectors, there are significant opportunities to capitalise on and protect future revenues,” added Sharma.

“This will require Australia to become a significant player in low-carbon hydrogen trade as well as being able to offer carbon storage and offset services,” said Sharma.

Australia’s Plan

“We will set a target to achieve net zero by 2050, and have a clear plan for achieving it,” Morrison said in an emailed statement Tuesday. “We won’t be lectured by others who do not understand Australia. The Australian Way is all about how you do it, and not if you do it. It’s about getting it done.”

Australia will invest A$20 billion ($15 billion) over the next decade in low emissions technology, according to the government. It provided the following breakdown on Tuesday but said it is still working on the modelling for the plan.

20%: Achieved reductions to 2020

40%: Technology Investment Roadmap

15%: Global technology trends

10-20%: International and domestic offsets

15%: Further technology breakthroughs

Source: Federal Government

The government will stick with 2030 goals that have been criticised by activists and business leaders alike as too weak, adding to the sense that timid pledges from developed nations are stifling prospects for major progress at the climate talks. Morrison on Tuesday reiterated that Australia was on track to “meet and beat” its target, forecasting a cut of as much as 35% by 2030 from 2005 levels compared with the official commitment for a 26-28% reduction.

“Investors are ready to invest billions, not millions, in Australia’s transition to net zero,” Rebecca Mikula-Wright, the chief executive officer of the Investor Group on Climate Change, said in a statement. “Australia not updating its 2030 target in line with commitments under the Paris Agreements is of deep concern to investors.”

Australia is one of the top suppliers of fossil fuels, and the sector accounts for almost a quarter of its export earnings. The nation is being looked at to help show leadership that’ll encourage developing countries to step up their efforts. Saudi Arabia, the biggest oil exporter, on Saturday pledged to a goal to hit net zero by 2060.

Morrison has frequently ruled out taxes for polluters and backed the country’s top emitters to devise the best solutions to help Australia hit net zero. On Tuesday, he said new coal-fired power stations could still potentially be built under his plan, with the fuel responsible for the bulk of the nation’s electricity generation.

That’s a blow for COP President Alok Sharma, who has struggled to win momentum for his ambition to “consign coal to history.” Nations like Australia and China, which is lifting coal output to ease an energy crisis, have resisted calls to phase out their own consumption of the fuel more quickly.

While every Australian state and territory — and key trading partners China, Japan, and South Korea — have committed to net-zero emissions, a national target was politically complicated for Morrison, who must hold elections by May and trails the main Labor opposition in opinion polls.

Lawmakers within the National Party, the junior member of Australia’s governing coalition, raised concerns over the threat to rural jobs, particularly in coal-mining communities, from an energy transition and demanded a series of concessions in return for their support.

The Australian newspaper reported that the Nationals had received a guarantee that the government would take no action to pursue a methane target. The US and the European Union have been seeking to use COP26 to announce that at least 35 countries joined a global pact to cut methane emissions.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg