With domestic supply in decline, Asia urgently needs to address its growing gas and energy needs. In the past few months, multiple energy crunches across the globe highlights that a flexible and reliable supply of energy is critical to keep markets and prices stable. In Asia, a growing gap between booming gas demand and falling supply is cause for significant concern.

An ongoing decline in indigenous production will mean a rising reliance on LNG imports, more price risk and less security of supply. A significant decline in upstream output is inevitable unless governments do more to incentivise both IOCs and NOCs to develop Asia’s valuable remaining gas resources.

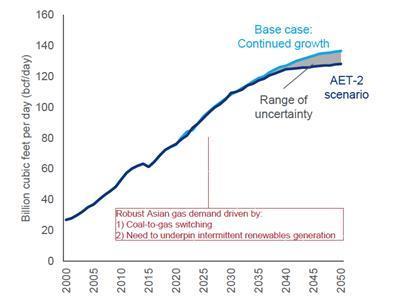

Our forecast for Asian gas demand growth is robust and resilient. It rises steadily through to 2050, peaking at just under 140 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d). Even under our Accelerated Energy Transition Scenario (AET-2), whereby global temperature rises are limited to 2° C, we expect demand to be almost as strong at 128 bcf/d. This robust demand will be driven by coal-to-gas switching as well as a need to underpin intermittent renewables generation. The use of renewables is growing rapidly across Asia, but with battery support still limited, the reliability of gas as a back-up is required to ensure the stability of the grid.

This strong demand profile makes Asia the engine-room for global LNG demand growth. This is driven not only by top-line demand, but also by declining domestic gas supply. This is forcing countries into a growing reliance on imported LNG via regasification terminals.

Domestic gas production is falling while 25 tcf of gas projects await FID

Asia is not short of gas resources, but it lacks commercially attractive opportunities. In terms of discovered resources, while 61 billion barrel of oil equivalent (boe) is already onstream, another 56 billion boe is discovered but considered non-commercial. The vast majority of these resources – over 70% – is gas, stranded due to a high level of contaminants, remote location and/or challenging fiscal terms.

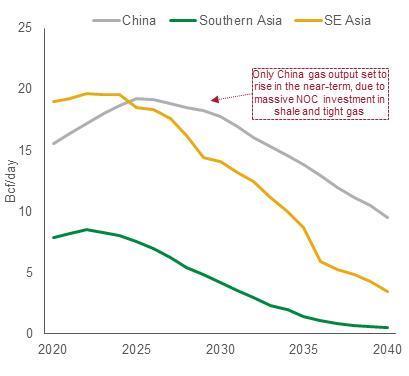

Of Asia’s three main producing regions, only China is growing gas output, due to heavy investment in shale and tight gas by its national oil companies (NOCs). Production in South Asia has been declining since 2010, and from 2015 for South East Asia. By 2025 both will reach a tipping point, in the absence of new investment and increased exploration.

The upstream outlook for much of Asia is not positive. Over 25 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of gas sits in pre-FID projects across Asia, but many are struggling to progress. Under half of the resource has an IRR of 12% or above at our base price assumptions.

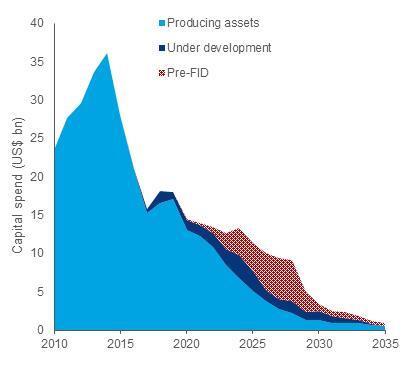

Overall capex spend and exploration activity are also both falling. There has been a huge decline in exploration & appraisal (E&A) activity across Asia, with an average of around 430 exploration or appraisal wells per year through the period 2000 to 2015 falling to a current annual average of well below 100 wells/year. (The previous numbers exclude China, due to an absence of reliable data)

Upstream capital spend across Asia (also ex-China) in 2021 is already around half that of just five years ago. It could fall by another 50% over the next five years if the current suite of pre-FID projects do not progress.

Governments across Asia must consider the knock-on effects of a decline in exploration and development spend by operators. Without new production coming through from fresh discoveries and sanctioned fields, country-level gas output – from predominately mature areas – will quickly decline.

This increases the level of dependency on imported LNG. In a scenario where future exploration upside is removed, import dependency across South East Asia hits 83% by 2035, exposing countries to significantly higher security of supply risk and price volatility risk.

Governments should consider incentives to spur increased activity levels and help develop indigenous resources where control of price, supply, taxation and revenues is far greater, versus importing energy.

Downside scenarios, coming to life

Recent near-term production data could inspire optimism. Many gas fields are enjoying a short-term rise in output thanks to higher prices and post-pandemic demand. However, this may hide deeper underlying issues. For almost two years many fields have had to postpone or cancel development programmes and regular maintenance due to both cost-cutting and the impact of the pandemic on rig, equipment and staff movement. Many operators fear this will lead to more equipment failures, unplanned outages and faster decline rates.

As was seen in recent global energy events, outages can have a significant impact. In H2 2021, a variety of problems reduced output from key Indonesian fields that supply pipe gas to Singapore. This in turn forced Singaporean generation companies to turn to the LNG spot market when prices were at record highs. By early November, a number of power retailers in Singapore had already gone into bankruptcy.

With many of the biggest gas fields that underpin supply in Thailand, Brunei, India, Indonesia and Malaysia now entering their fourth decade of production, the risks are growing that these ’foundation fields’ decline faster than expected, further exacerbating the supply gap.

Examples are already emerging: we have slashed our forecast of Myanmar gas exports to Thailand as the aging Yetagun and Yadana fields have fallen far faster than initially expected. In addition, the country’s sole pre-FID project, the 2 tcf Block A6 development, was cancelled following a military coup.

For Thailand, this means the loss of an expected 300 mmcfd of imported gas. Combined with its ongoing decline in domestic production, this accelerates the country’s dependency on imported LNG, which could hit 100% by 2038 based on current commercial reserves. Is this a preview of what awaits for other countries in Asia?

Fiscal policies are critical

Most fiscal structures for oil and gas development across Asia have been in place for decades. Given the rapid evolution of the industry in just the last two years due to the energy transition, and the rapid increase in the importance of asset decarbonisation, are current regulation and incentives fit-for purpose?

Governments must ask themselves some increasingly urgent questions – what is the goal of our current oil and gas fiscal structure, and is it set-up to achieve that goal?

In previous price up-cycles this would translate to a proportionate increase in regional upstream spend. This time, however, the activity response will be dampened, as the IOCs have fewer priority projects in the region and are focusing spend on advantaged basins in other areas of the world. And NOCs cannot carry the entire upstream future of their country on their backs alone.

Because upstream companies are set for a period of increased profitability, any discussion around increasing incentives will be politically challenging. However, the reality is that under current strategies less and less of that income will be spent on Asian upstream operations, and as such local regimes must compete harder for future investment dollars.

Alternatively, incentives can flow through to other sectors – such as renewables, with due consideration of how their intermittency will be supported, and the impact on LNG import dependency.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Woodmac

© Supplied by Woodmac © Supplied by Woodmac

© Supplied by Woodmac © Supplied by Woodmac

© Supplied by Woodmac