Thailand’s upstream natural gas sector is struggling to reverse falling output due to bad planning and policy from the government, coupled with a seeming lack of innovation at PTT Exploration & Production (BKK:PTTEP), a state-backed company, that is taking increasing control of the country’s gas resources.

Falling domestic gas supplies from the Gulf of Thailand have led the Southeast Asian nation to import more liquefied natural gas (LNG) amid surging global prices, which has significantly weakened the country’s energy security. Natural gas is a key fuel for power generation in Thailand, as a result, the Thai people are facing much higher electricity bills. Moreover, reports suggest Thailand is at risk of a fuel crunch with imported LNG becoming too pricey.

Significantly, the share of LNG in the country’s total gas supply has jumped to 40%, up from 20%, while domestic gas supply’s share fell from 64% to 40%, the Bangkok Post reported on 20 June, noting that power prices will hit an all-time high this year. Piped gas imports from Myanmar, which make up the remaining supply, are also falling.

The expanding demand for LNG is being exacerbated by production declines across ageing domestic fields. Field by field production data confirms long-term output downtrends across most of Thailand’s larger gas fields. The most prominent being ongoing declines at the Erawan field in the Gulf of Thailand.

But the decline at Erawan was avoidable. Crucially, industry observers believe that under the right government direction, coupled with innovative technologies, much more natural gas can be unlocked in Thailand.

The Erawan Fiasco

Erawan, the country’s largest gas field, was the center of a wholly-avoidable dispute with Chevron (NYSE:CVX) , which is now hitting home.

Erawan accounts for about a third of Thailand’s domestic gas production despite output having peaked in 2014. Thailand’s state-owned oil and gas company PTTEP took over operations at the field from Chevron in April 2022 after winning rights to the legacy field in an auction held in 2018 by placing a low bid. Some observers viewed this as effectively nationalising the Gulf of Thailand resources.

However, the process leading up to PTTEP’s scheduled takeover was far from smooth, particularly in recent years, due to a bitter legal dispute between outgoing operator Chevron and the Thailand Ministry of Mineral Fuels (DMF) over decommissioning fees.

Due to the dispute between Chevron and Thailand’s government, PTTEP was unable to start early drilling works needed to stem falling output at Erawan. The need for a smooth handover between operators was especially acute in the Gulf of Thailand, where gas deposits are found in relatively small pockets. Every year hundreds of wells need to be drilled across the Erawan field to maintain output.

Erawan’s gas production has fallen from 1.2 billion cubic feet per day in 2020 to under 400 million cubic feet per day (mmcf/d) now. That has forced the government to approve a plan to import an additional 4.5 million tonnes of gas this year, equivalent to 178 billion cubic feet, bringing Thailand’s total natural gas imports to an estimated 9.7 million tonnes this year.

Energy Voice understands from industry sources that Chevron had engaged with Thailand’s Department of Mineral Fuels (DMF) since 2013 on ways to avoid this expected production decline, including advising in 2016 that significant investment would be necessary just to maintain existing production levels – investment Chevron could not make because of uncertainty over operatorship of the concession.

Assuming the Erawan drilling hiatus has not had any adverse subsurface effects, it could take many years, if at all, before PTTEP reaches the contractual minimum production rate of 800 mmcf/d, at the Erawan production-sharing contract (PSC).

There are also concerns about PTTEP’s partner Mubadala Petroleum. Mubadala’s interest in its Thai portfolio could be waning, as the company is seeking to divest its Southeast Asia assets. The UAE-based company has a 40% interest in Block G1/61 containing the Erawan field.

Is PTTEP Up to The Challenge of Reviving Gas Production?

PTTEP is now tasked with reviving output at Erawan. But this will not be easy for the state-backed upstream player that arguably lacks an innovation heritage.

Unocal first discovered natural gas in 1973 in the Gulf of Thailand. In 1978 the field was officially named “Erawan”, after a mythical three-headed elephant symbolising power. In 1981, the US-based oil company started initial production and by 1986 was pumping 321 mmcf/d. Output jumped by 70% to 548 mmcf/d in 1988.

Using innovative drilling techniques Unocal saw production hit 758 mmcf/d in 1993 and by 1998 output has reached a record 1 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d), up 87% from ten years earlier.

A former member of the Unocal team told Energy Voice that “the company went from conventional well design to unconventional. Nobody else was drilling how Unocal did.”

In the 1990s, Unocal slimmed down its well design. This provided a step change and cut the cost per well from between $4 million and $5 million to less than $1 million. “They learned to drill wells like a factory process,” added the source.

In 2005, Chevron absorbed Unocal and took control of Erawan. Between 2005 and 2011 Chevron maintained gas production at around an average rate between 900 mmcf/d and 1 bcf/d. However, output surged to 1.386 bcf/d in 2012 and hit a record high of just over 1.4 bcf/d in 2014, after Chevron had understood, applied, and improved upon, Unocal’s innovative drilling methods.

Initially, Chevron, one of the best global oil companies, struggled to understand Unocal’s drilling model. Still, it took Chevron, which has excellent project management systems, only a couple of years to figure it out. They created a factory model, customised their own rig design, developed an engineering process, and built bespoke equipment that allowed them to produce in better ways by drilling 300-400 wells per year. Between 2015 and 2019 production averaged around 1.3 billion cf/d.

However, once PTTEP officially signed PSCs for the Erawan and Bongkot fields in February 2019, after beating Chevron for the operatorship of the fields in December 2018, the US company subsequently started to scale back its investment at Erawan. Consequently, production fell from about 1.185 bcf/d in 2020 to 545 mmcf/d by December 2021, according to government data.

There was planned to be a smooth transition between Chevron and PTTEP at Erawan, but an arguably avoidable dispute between the US company and the Thai government over who would eventually be liable for decommissioning costs at Erawan scuppered that plan.

PTTEP reported that, on the date of operatorship handover in April 2022, the natural gas production rate at the G1/61 Block, which covers Erawan, was at 376 mmcf/d. The lowest level recorded since January 1987.

PTTEP hopes to double output within two years. However, this seems doubtful given it took Chevron, one of the world’s best oil companies, at least five years to significantly boost production once it started operating the field in 2005.

It is worth noting that PTTEP has operated the nearby Bongkot field since 1998, which produced 202 mmcf/d in 1994, its first full year of production. Output peaked in 2015 at around 1 bcf/d, but by the end of 2017 that level had almost halved and has hovered around 500 mmcf/d to 550 mmcf/d since then.

The Thai company was simply not drilling enough wells at Bongkot. “They were drilling 60 to 80 wells maximum per year and wondered why it started to go into decline. By comparison, Chevron was drilling 300-400 wells yearly and pumping 1.4 bcf/d at Erawan. Bongkot has a great reservoir like Erawan too,” a source close to the project told Energy Voice.

Moreover, PTTEP may never recover production at Erawan, as the company needs to go from drilling 100 to 400-500 wells per year, added the source.

This will be challenging, as the supply chain would be tough at the best of times, but it will be even worse in today’s economic environment. Aside from buying additional drilling rigs, PTTEP also needs to build new wellhead platforms and subsea pipelines. But “the biggest hurdle will be PTTEP’s mindset. It’s not in the right place. Chevron almost did not unlock the key to Erawan when it took over, but eventually they improved the Unocal model. PTTEP does not have the right innovative approach yet,” said the source.

In December 2018, after PTTEP had beat Chevron to the contract extension for Erawan, PTTEP’s former chief executive, Phongsthorn Thavisin, said that the company has “accumulated a sound technical understanding of both fields (Erawan and Bongkot).”

He added that “our proposed development and investment plans will enable us to produce natural gas at the required production levels of at least 700 mmcf/d and 800 mmcf/d from the Bongkot and Erawan fields.”

But at that time PTTEP was already apparently struggling at Bongkot – output had halved. Some industry observers saw the Thai company’s triumph with a low-ball bid for Erawan as the start of effectively nationalising the country’s upstream sector.

At the same time, Chevron said that it was “deeply disappointed that it was not the preferred bidder for the Erawan and Bongkot blocks. Chevron submitted credible, sustainable bids, built on our deep experience operating in the Gulf of Thailand.”

“Our bids allowed for the necessary investment to maximise recovery of Thailand’s resources,” added Chevron.

Perhaps, with hindsight, Chevron might have been the more pragmatic choice to run Thailand’s largest gas fields. Moreover, the country might now be less reliant on expensive imports of LNG to power the nation and could have avoided a looming energy crunch.

Natural gas production from the Gulf of Thailand costs roughly no more than $5-6 per million British thermal unit (Btu) versus long-term contracted LNG prices of around $10-12/million Btu. In mid-June Asian LNG spot prices breached the $38/million Btu mark.

Thailand Needs a Shale Gas Moment

A former engineer that has worked on Thailand’s major gas fields told Energy Voice that the country needs a shale gas type breakthrough. By this he means using technological innovation to unlock more reserves by hitting the sweet spots cheaply and profitably, just like Unocal and Chevron did.

“There is a lot more natural gas in the gulf, it’s just that operators don’t know how to produce it. It is possible to pump more than 1 billion to 2 billion cubic feet per day at Erawan. It is also possible to double Bongkot’s production rapidly if Chevron’s models are adopted,” said the engineer.

Crucially, it did not take Unocal too long to unlock more reserves in the gulf as the company was relatively small and able to operate nimbly. It took Chevron, a much larger and therefore less nimble company, quite some time to improve productivity. And PTTEP are not there yet. “I don’t see PTTEP getting there within two years, it could take them five to ten years, if at all. They have a different mindset and different business process, as they are run under a state enterprise. Nobody is willing to stick their ass out to make things better. It needs leadership at the very top to embrace new ideas,” added the engineer.

Unlocking More Natural Gas in Thailand

According to data from BP, Thailand’s proved natural gas reserves stood at 0.1 trillion cubic metres at the end of 2020, down from 0.4 trillion cm in 2000. But some analysts and industry executives believe there is plenty more natural gas waiting to be recovered. Indeed, they point out how other mature provinces, such as the Gulf of Mexico and the North Sea, have revitalised production using new strategies to attract investment.

However, given PTTEP now operates the lion’s share of the nation’s gas output, it will be next to impossible to entice any of the larger players into Thailand, Readul Islam, an Asia upstream specialist at Rystad Energy, told Energy Voice.

Meanwhile, a large regional exploration and production player looking for acquisition opportunities in Southeast Asia, recently told Energy Voice that it has ruled out Thailand, as PTTEP dominates the upstream now.

Even Thailand-based upstream players, such as Banpu, are staying clear of their home country. Banpu—controlled by billionaire Isara Vongkusolkit and his family— in May agreed to buy natural gas fields in Texas from ExxonMobil for $750 million as the Thai coal miner accelerates its transition into cleaner energy. The transaction lifts Banpu’s daily gas production to 900 mmcf/d, including assets in Pennsylvania bought in 2016 and the rights in the same region of Texas acquired in 2019.

Crucially, Thailand should take note that effectively nationalising the upstream oil and gas sector, which dulls any sense of commercial acumen, has never been a recipe for successfully boosting output elsewhere in the world, except for Saudi Arabia, where Aramco has all sorts of technical service companies assisting.

Rystad’s Islam believes Thailand must attract smaller nimbler specialised operators to enhance energy security. Such companies, with lower cost bases, would be more adept at eking out more molecules of gas, leaving PTTEP to focus on extending the life of its large legacy fields, he said.

Incentivising new operators to tap smaller fields and late-life assets with incentives and higher gas sales prices would help too. Malaysia has demonstrated how such a strategy can prove successful.

“It takes time to get new operators in, but a strategy, similar to Malaysia’s, attracts a whole new bunch of talent, new capability, and that gives you an extra 10-20% of production that makes a difference,” said the engineer that has worked on Thailand’s big fields.

And there is potential for more gas. Industry professionals believe the Thailand-Cambodia Overlapping Claim Area (OCA) in the Gulf of Thailand could easily hold another Erawan and Bongkot. However, there has been little progress on mutually beneficial agreements for the countries to develop the area.

Domestic Gas, Petrochemicals, and Taxes

Erawan not only supplies gas for power plants, but also the huge Thai petrochemical industry in Rayong Province, which is a major user of C3 and C4 fractions – such as propane, propylene, n-butane, isobutane, butylene etc – extracted from the domestic gas. While imported LNG can replace the gas used for power generation, the petrochemical industry could face a shortage if the gas from Erawan stops flowing, as LNG does not contain the critical C3 and C4 fractions required.

Not only is gas produced from the gulf of Thailand cheaper than imported LNG, as well as crucial for the petrochemical industry, but it also gives the Thai economy a natural advantage through taxation, royalties, and jobs, unlike LNG imports.

Ultimately, the government of Thailand needs to give its upstream oil and gas strategy a proper rethink. Relying increasingly on imported LNG over the development of domestic resources will leave the Thai people paying higher than necessary prices for energy due to poor planning and policy. Allowing PTTEP to monopolise the upstream sector will also stifle much-needed competition, innovation, and entrepreneurial activities that a diverse pool of operators could bring.

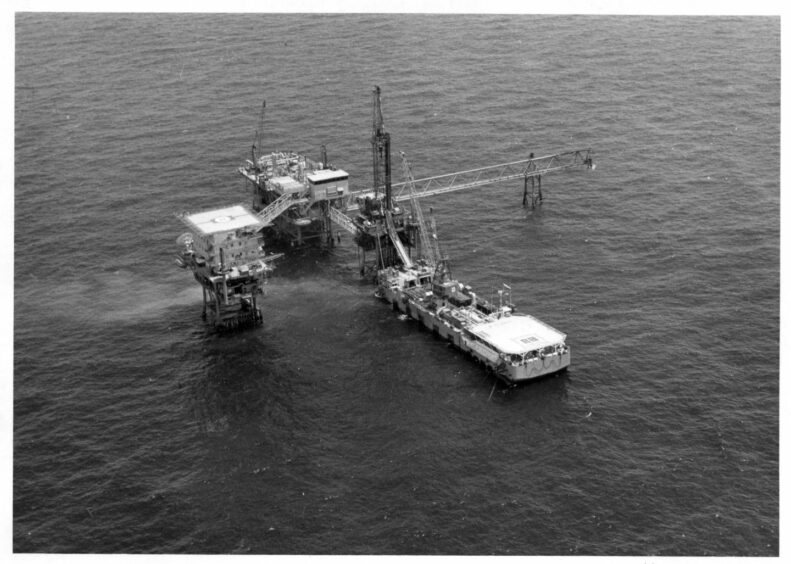

© Supplied by Chevron

© Supplied by Chevron © Supplied by Chevron

© Supplied by Chevron © Supplied by Chevron

© Supplied by Chevron © Supplied by Chevron

© Supplied by Chevron