Unlike most governments in the economically developed Western world, Indonesia’s leaders are crying out for more upstream oil and gas investment. However, even as demand is projected to rise up to four times by 2050, Southeast Asia’s biggest economy is struggling to convince energy investors to come.

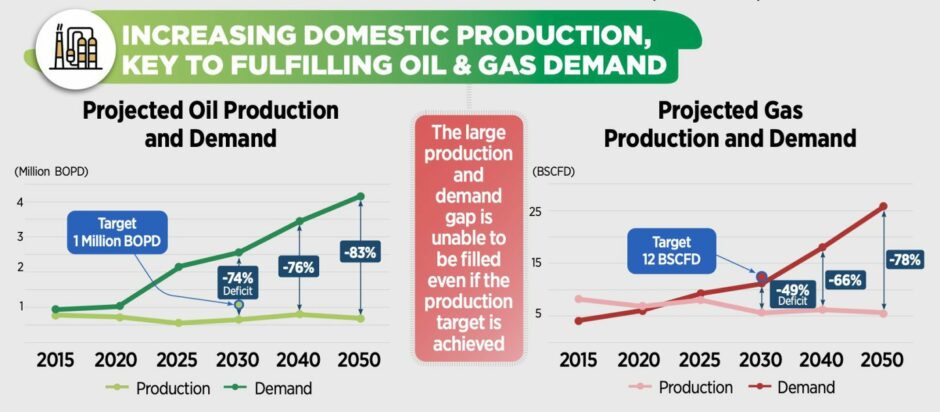

Population growth, economic expansion, and higher living standards are among the factors pushing greater energy demand. On Wednesday, delegates at the Indonesian Petroleum Association (IPA) conference in Jakarta heard that oil demand is expected to increase two times, while natural gas demand will rise four times by 2050. In 2021, about 1.471 million barrels of oil were consumed daily in Indonesia and natural gas demand stood at 37.1 billion cubic metres for the year, data from BP showed.

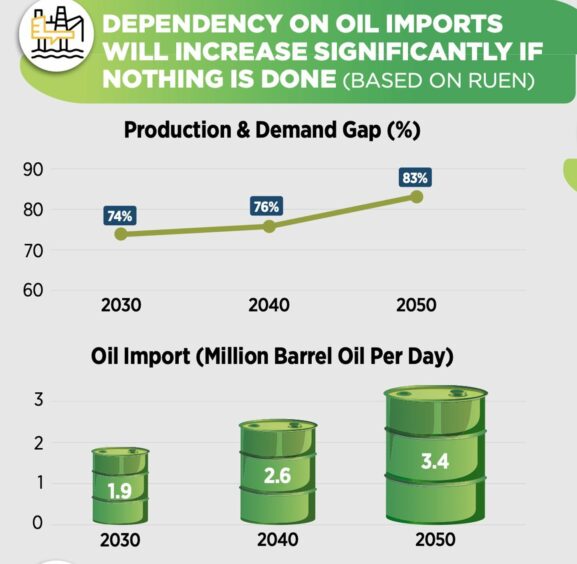

The government has set a production target of 1 million barrels per day (b/d) of oil and 12 billion cubic feet per day (cf/d) of gas by 2030 in an effort to improve energy security and lower its oil import bill. Oil output was 696,000 b/d in 2021 – it has been trending down from a peak near 1.6 million b/d recorded in 1991. Gas production was 6.6 billion cf/d in 2021 – of which 64% was consumed domestically and the rest exported.

To hit the 2030 output targets, an estimated $200 billion will be needed, a substantial amount, especially at a time when global funds available for oil and gas investment are falling. But time is running out and the government must compete fiercely with other countries that are successfully attracting oil and gas investment by implementing tactical fiscal and non-fiscal policies, argues the IPA.

Political Meddling

The trouble is Indonesia’s upstream sector has struggled in recent years, largely because of political meddling and, as a consequence, the uncertain business environment, coupled with the rise of resource nationalism, under President Joko Widodo, since he took power in October 2014.

Major foreign investors, such as TotalEnergies and Chevron, that had successfully helped make Indonesia the largest hydrocarbons producer in Southeast Asia, were effectively forced out. Another big hitter, ConocoPhillips, divested its upstream assets in Indonesia last year. Meanwhile, Shell, one of the world’s best liquefied natural gas (LNG) developers, remains desperate to exit the Masela project after President Widodo, known locally as Jokowi, personally vetoed the FLNG development plan, approved by the government, for the Inpex-led scheme in 2016.

The poor decisions made under Jokowi’s watch cannot be undone. However, positive noises were made by senior officials from the energy ministry and Commission VII – a special parliamentary committee devoted to energy and mining – during the IPA conference. A long delayed, and much needed oil and gas law, that should provide legal certainty for investors, is promised to be finalised in 2023. There were also signals that foreign upstream investors would be treated more fairly, instead of the government prioritising and championing Pertamina at all costs. Maman Abdurrahman, vice chairman of Commission VII, admitted radical action was needed and promised to push other ministries, such as finance, harder, otherwise, he said oil production would keep falling towards the 500,000 b/d mark.

Indeed, the energy ministry and upstream regulator SKK Migas have shown an increasing willingness to be more flexible when negotiating terms and conditions for upstream investors. Eni (MIL:ENI), ExxonMobil (NYSE:XOM), BP (LON:BP), and Harbour Energy (LON:HBR), all remaining operators in the archipelago, applauded the improvements.

More Needs To Be Done

But more needs to be done. The IPA hopes that legal certainty, ease of doing business, licensing, and fiscal policies will continue to be reformed and improved. Moreover, there needs to be some certainty around carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions management and gas as a transitional energy policy.

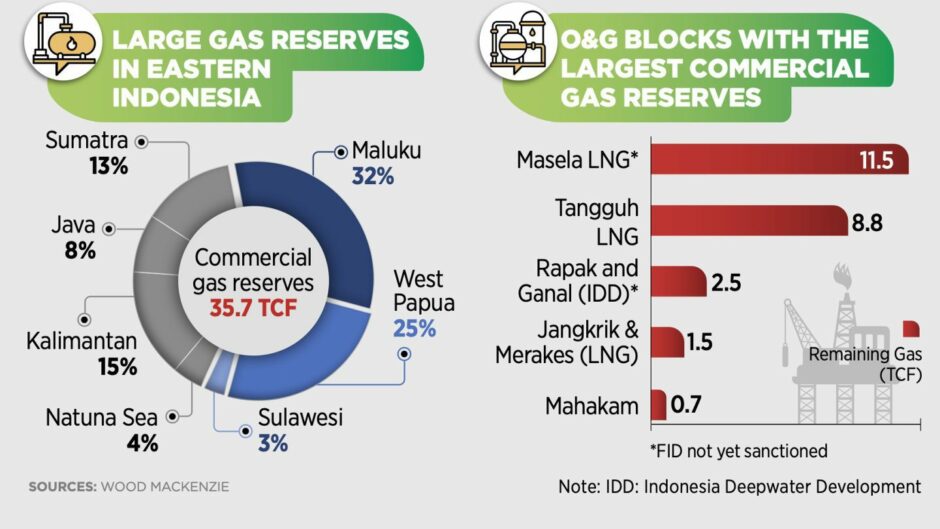

The general sense is that Indonesia is more likely to hit its 2030 gas production target than its targeted oil output. There are numerous discovered gas resources that could be developed with the right incentives, however this is less so for oil. Commercial gas reserves stand at 35.7 trillion cubic feet, data from Wood Mackenzie shows.

Still, the urgency of a new gas price policy to help the nation hit its 2030 output remains a significant hurdle to overcome. In Indonesia the regulated gas price for electricity and seven other sectors is $6 per million British thermal units (Btu). A price of $6/million Btu for the end user, typically results in a price of around $5/million Btu or less at the wellhead. Only about 30% of the planned gas development projects in Indonesia are considered economic at $5/million Btu. Significantly, global oil and gas companies operate around 90% of potential gas development projects in Indonesia, therefore rates of return must be globally competitive to attract investment. Market pricing, as seen in many Southeast Asian nations, would be welcome.

Crucially, there has been no discovery of large oil reserves and a general lack of exploration. This needs to change and the government must incentivise investment, not just talk about it. There is no doubt about Indonesia’s potential – it has 128 basins and 70 of those are unexplored. But without investment that potential will never be realised.

Urgent Radical Action

Indeed, radical action needs to be taken urgently within the next year to shake up investment in Indonesia’s upstream if there is a remote possibility to arrest and reverse current production trends. While the energy ministry and SKK Migas understand what needs to be done, other crucial areas of the government, such as the finance ministry, need to be onboard.

Ultimately, action from the highest level is needed for an upstream renaissance in Indonesia. President Jokowi has one last chance to reverse his administration’s woeful handling of the oil and gas sector. Otherwise, his government will be remembered for sowing the seeds of the looming energy crisis facing Indonesia.

Sadly, with all the political jockeying expected next year ahead of presidential elections in 2024, it is hard to imagine much progress around fiscal and non-fiscal policies. Unfortunately, as one senior Indonesian oil and gas executive remarked, Jokowi will be more interested in securing his legacy relating to benefits for his political party and family, rather than taking much-needed gutsy action and going against the grain.

© Supplied by IPA

© Supplied by IPA © Supplied by IPA

© Supplied by IPA © Supplied by IPA

© Supplied by IPA