A group of companies say the “stars are aligning” for the development of a new single-lift construction vessel (SLCV) which could take a chunk out of North Sea decommissioning costs.

The vessel has been designed, costed, tested and approved – and construction yards have been identified.

So what’s the hold up?

The consortium has cleared many hurdles, but is short of a key ingredient – a big boy prepared to stump up the funds for the build.

Alex West, director at Ayrshire-based consultant Westlord Associates, said the consortium came close to bringing in key partners on a number of occasions.

The vessel was on the shortlist for Ekofisk and Frigg decommissioning jobs, and more recently was in the design competition for Brent Delta, but fell short each time.

Mr West said: “We are ready for a construction yard to do the detailed design, about six months before cutting steel.

“What we are waiting for is to get a couple of key partners in place before private equity people will pile in with funding.

“We’ve been close with that a couple of times. The problem with any decommissioning project is that the dates keep changing.

“It’s not easy to get companies to commit to a strategy.”

The group of companies behind the project is led by Stavanger-based Ocean Services, which has an agreement on the use of vessel design licence with Global Maritime, a marine warranty consultant.

Other partners include Chinese firms CIMC and Cosco, which both have fabrication yards in China, and Westlord Associates, which is trying to coax operators and supply chain companies into getting involved.

Mr West said Ocean Services had a track record of “getting things built”, particularly in China.

Ocean Services intends to set up a special purpose company which would own the SLCV and market it to oil companies to secure decommissioning projects.

Ocean Services has the skills and competence to operate the vessel, but Mr West believes the project needs the involvement of a big name.

He said: “We’re looking to set up a consortium with financial stability and a strong company behind it.

“We’ve talked to vessel operators and support companies, the sort of ones that would staff and maintain the vessel.

“What we’re really looking for are the sorts of heavy-lift companies that want to get into platform removal, or engineering companies who want to offer a full decommissioning service and will take ownership of the vessel and operate it.”

He said a supply chain company was probably the best bet: “The way operators are moving, it is unlikely they could take it on themselves. They might if they’re the sort of company that can see there’s a long-term interest in this type of vessel, but there aren’t many of them around.

“The operator community seems to be coming together to say they have to do decommissioning, but it isn’t something they want to do as part of their core business. They want the supply chain to be able to do it.

“So we’re looking for the sort of supply chain companies that are able to be the anchor of the consortium.”

Mr West is adamant that now is the right time to start cutting steel, because of the number of decommissioning projects likely to start coming up after 2020.

“When I’ve talked to the investment community, they are happy with the market survey in terms of the decommissioning projects that are coming up,” he said.

“Some dates for (cessation of production) are being extended, but they don’t have any qualms about the market being there, it’s just a question of timing and the oil companies having cash flow.”

A lot of time has gone into the SLCV already – more than a decade. And 50million NOK (£4.7million) has been invested in the project, but more cash will be needed to get it off the ground. It is expected to cost £235-£275million to build, which seems like a lot. However, stacked up against Allseas’ Pioneering Spirit, which had a sticker price of £2.4billion, the SLCV looks like a snip.

The vessel would use less steel, the lifting systems would be less complicated, and it wouldn’t have all the bells and whistles characteristic of ships operating in the decommissioning market. Mr West said many of those features simply aren’t needed.

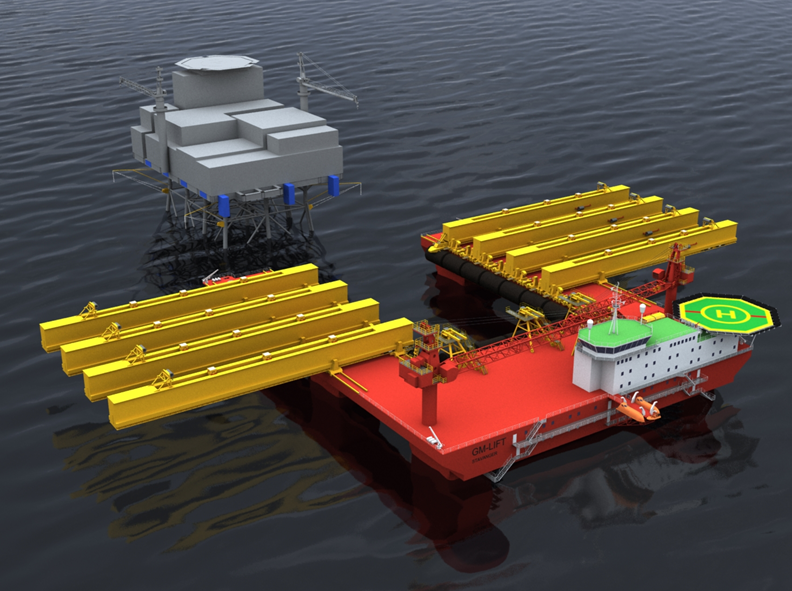

The SLCV is similar in appearance to a semi-submersible rig, but would have adjustable lifting beams which would be positioned under the topside module.

The topside structure would then be lifted by ballasting and de-ballasting using the displacement of water.

It would be able to lift topsides weighing up to 23,000-tonnes, which covers 85% to 90% of the market. The vessel could be built in three years flat, given that Chinese yards currently have a lot of excess capacity.

The SLCV is far from being the only design on the market, but Mr West is confident it has a competitive edge.

He said: “The appeal to me is that it’s had a lot of investment from Global Maritime in the design. Global Maritime has strong credibility in semi-submersible design, anyway.

“They’ve taken it through DNV approval, and they have pre-qualified on a number of large operator projects.

“The thing that has held it back is that oil companies have always said to any new design, ‘show me where it’s worked before, show me that it’s built and I might put you on the bid list.

“Of course, we’re not a group with the kinds of resources Heerema has. We can’t put a lot of our own money behind it.”

“But we are very strong in knowing the vessel can be built for a certain price, because Ocean Services has a long track record now in building semi-submersible-type platforms in China.

“There is a lot of experience in the team. The design is pre-qualified. It’s just a case of finding a company that says, ‘yep, we recognise the time is right to be taking on the Heerema, Allseas competition’.”

Recommended for you