Europe’s biggest oil companies are gaining support from an unlikely source as they confront the industry’s worst slump since the financial crisis: lower oil prices.

Although better known for their oil fields, refineries, and petrol stations, BP, Royal Dutch Shell and Total are also the world’s biggest oil traders.

Together, they handle enough crude and refined products every day to meet the consumption of Japan, India, Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands.

The trio’s sway in commodities trading, largely unknown outside the industry, is set to pay off in 2015 as the bear market allows traders to generate higher returns by storing cheap oil today to sell at higher prices later – and use lower prices to make more bets with the same capital.

“Volatility has increased dramatically over the last three or four months,” said Mike Conway, the head of Shell’s trading and supply business, adding: “Parts of your business that are volatility driven are probably doing pretty well.”

While companies are shy about revealing the financial results from their trading business, a look at the last major bear market provides clues to the opportunities.

In the first quarter of 2009, BP said it made £334million above its normal level of profits from trading. That means that trading accounted for at least 20% of BP’s adjusted income of £1.6billion that quarter.

From dealing floors that resemble the operations of Wall Street banks in cities including Geneva, London, Houston, Chicago and Singapore, oil trading could provide BP, Shell and Total with an edge over US rivals.

ExxonMobil and Chevron sell their own production but largely eschew pure trading as a means of generating profits.

Few other publicly-listed oil companies trade at the scale of the European trio, although Statoil, Eni and Lukoil all have trading desks.

The amount of crude oil and fuel traded each day by the three European majors easily beats the combined size of independent traders such as Vitol, Glencore, Trafigura, Mercuria, Gunvor, according to company statements and industry insiders.

The last time a European oil major disclosed the profitability of its trading operation was a decade ago, when BP said it made nearly £2billion in 2005, or about 10% of its total earnings that year.

Without giving away concrete financial results, the companies have indicated income from trading already rose in the fourth quarter of 2014 as oil prices fell.

On February 3, BP chief financial officer Brian Gilvary said the group had benefited from an “improved result from supply and trading.” Mr Gilvary ran BP’s trading arm from 2005 to 2009.

“We’re in a very strong commodity trading position,” Shell chief financial officer Simon Henry said in a call with analysts on a January 29.

“Our ability to take advantage of volatility is some protection to mitigate the low price environment,” he added.

BP and Shell declined to comment further. Total didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Although extra profits from trading won’t offset much larger loss of revenue from lower oil prices, it could help the three companies to weather the crisis.

Beyond the large oil producers, traders are optimistic they can reap strong profits in 2015.

Glencore chief executive Ivan Glasenberg has said that if the market continues as in the first two months, oil trading “could have a blow-out year” in 2015.

In the past, oil trading houses have enjoyed stronger returns during bear markets.

Vitol, the world’s largest independent oil trader, had record income of £1.5billion in 2009, up from £909million in 2008, according to the company’s accounts.

Fitch Ratings anticipates that oil traders “are likely to report healthy earnings in 2015 as they benefit from volatile oil prices”.

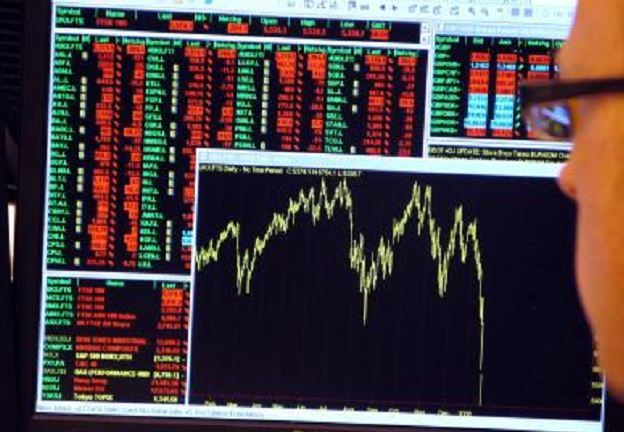

Several factors explain the expected rise in income. First, after years of steady prices, volatility has surged – allowing traders to make more bets about the direction of the market.

Secondly, oversupply has pushed oil prices into a structure called contango – a relatively rare situation where forward prices are higher than current prices, allowing traders to buy oil cheap, store the commodity and sell later.

Lower oil prices also mean it takes less capital to make trades.

The price difference between a Brent contract for immediate delivery and the one-year forward – a measure of the contango – stood at minus $7.18 a barrel yesterday. The spread hit an all-time high of minus $17.93 in December 2008.

Brent for delivery in April is today trading at $58.09 a barrel, 46% lower than a year ago.

Read more Europe news here.

Recommended for you