The pace of North Sea oil and gas decommissioning continues to lag behind targets, with operators who fail to comply being liable to face fines of up to £1 million.

More than 500 inactive oil wells that are legally required to be deconstructed, cleaned and sealed over under UK law have missed their original deadline, a spokesperson for the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) confirmed to Energy Voice.

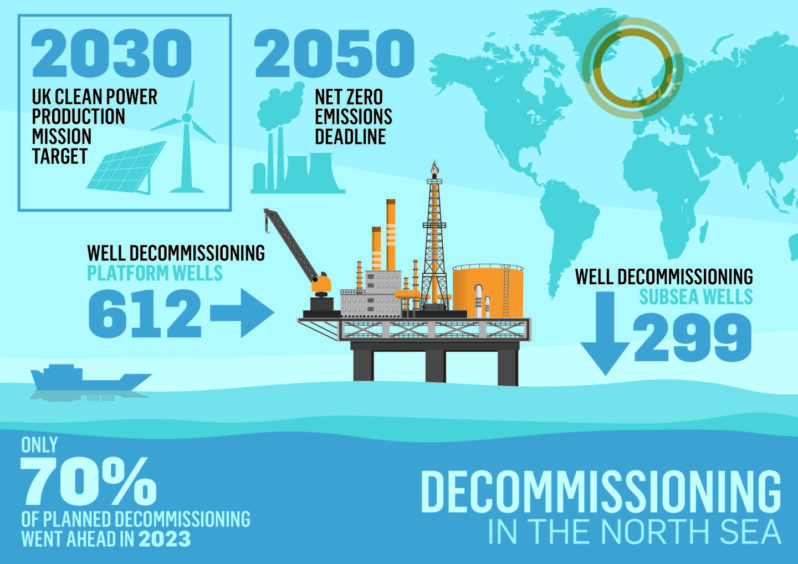

UK operators of oil rigs in the North Sea “only achieved 70% of planned well decommissioning activities last year”, the NSTA warned this July.

“I am concerned that this huge opportunity to safeguard highly-skilled jobs and support the transition will be wasted if operators fail to tackle their well decommissioning backlogs,” Pauline Innes, the NSTA’s supply chain and decommissioning director, said in a report this July.

According to the decommissioning authority, North Sea operators, confronted with high and rising costs, are still behind schedule for decommissioning oil wells and substructures, and those that fail to comply could face investigation and possible fines.

“They’re certainly behind,” an NSTA spokesman told Energy Voice.

“That isn’t good enough. We are working with the companies to see why they are behind with their obligations and how they can get back on track.”

Operators that fail to decommission old unused oil fields on time could face investigation.

In July, NSTA supply chain and decommissioning director Innes warned North Sea operators to accelerate the rate of industrial oil rig decommissioning and said the authority would launch investigations into those that do not complete decommissioning on time.

Decommissioning still behind

An NSTA confirmed to Energy Voice that it is “losing patience” and opening investigations into operators that fail to decommission old oil rigs on schedule and miss deadlines for taking old wells out of operation.

“Yes they will face sanctions,” the NSTA’s Belgard told Energy Voice, who confirmed by email that, “the maximum sanction available is a £1 million fine.”

At present, there are 940 inactive wells that need to be decommissioned and more than 500 that have “missed their original deadline”, according to the latest data shared by the NSTA.

Although operators could face fines for slow decommissioning, regulators indicated willingness to work with companies to improve stewardship when plugging up old oil wells and removing subsea structures in practice.

“There are theoretical penalties because they are in breach of their licence condition,” the NSTA said.

“We prefer to engage in stewardship rather than wave sticks at people. We work very closely with a lot of companies that are behind in their decommissioning.”

The regulator added: “120 wells have been decommissioned on average per year from 2018 to 2023”.

Data on the NSTA website on the latest updated decommissioning data visibility dashboard that was expanded in February suggests that UK operators are in the process of decommissioning 612 platform wells which must still be decommissioned and 299 subsea wells by 2029, based on data provided by a total of 15 operators.

In the first instance, the NSTA would look to work with operators who miss their deadline to decommission old oil wells and if that is not possible “then we’d look at taking action”.

UK law broadly requires that any oil and gas infrastructure on the continental shelf that has stopped production must be removed, with the exception of some submerged pipelines.

Decommissioning is regulated by the Petroleum Act 1998, the Energy Act 2008 and Energy Act 2016 and the plugging of old oil fields is viewed as a key part of the energy transition.

One potential opportunity for marrying decommissioning obligations with energy transition goals is in repurposing old oil wells for carbon capture and storage.

Old oil fields can be repurposed for carbon, capture, usage and storage, whereby liquefied or gaseous carbon dioxide captured from waste flue emissions can be stored deep under the sea’s sediment in old oil fields and then sealed over to prevent leakage.

Carbon capture will be a key beneficiary of £22 billion of government funding at low-carbon clusters in Teesside and Merseyside over the coming years.

Financial hurdles

Research and data firm Moody’s published a report in October 2024 that estimated the aggregate decommissioning liability for companies in its analysis was $22.4 billion, representing “more than 50% of total liabilities for some operators in mature basins”.

Analysts warned that annual decommissioning costs “keep rising” and are expected to total £2.4 billion a year on average to 2032 for the UK’s North Sea.

Carbon capture and storage “could delay decommissioning costs and diversify business profiles” further, analysts said, adding that carbon capture activities are “unlikely to neutralise carbon transition risk exposure”.

The Moody’s report anticipated that oil and gas companies with European downstream operations, where oil and gas are converted into final end products, will report “much lower earnings” from these activities over the next 12 to 18 months.

Preem Holding, Neste, CEPSA, MOL Hungarian Oil and Gas PLC, and Orlen SA, are expected to be among the most exposed.

Meanwhile, Shell, Total Energies, BP, ENI, Repsol and OMV’s impact is expected to be “more balanced”, analysts said.

Moody’s analysts Maria Chiara Caviggioli, Richard Etheridge and Dasa Patrikejeva said “Carbon capture and storage could delay decommissioning costs and diversify business profiles, but is unlikely to neutralise carbon transition risk exposure.

“Offshore oil producers could leverage CCS as depleted reservoirs offer potential CO2 storage sites. This approach may postpone decommissioning, support business model resilience during the carbon transition, and provide additional revenue.

“However, the potential for CCS currently appears limited due to finite storage capacity and the improbability of reopening already decommissioned fields.”

Moody’s said that for most companies within its sample of small to midsized entities, such as Harbour Energy and Ithaca Energy, the activities relating to retiring assets absorb an estimated 10% to 15% of operating cash generation.

These costs as a proportion of cash are lower for other independent producers such as Aker BP, the analyst said.

“At the end of June 2024 the cumulative obligations were estimated at $22.4 billion,” the Moody’s report said. “The cost of decommissioning liabilities is rising, particularly in older basins.”

According to the NSTA, from 2023 to 2032 about £24 billion is estimated to be spent on decommissioning by operators, a £3bn increase on prior estimates.

According to the UKCS Decommissioning Benchmarking Report 2024 this September, challenging economic conditions have led to “an overall increase” in the cost estimates for decommissioning in the continental shelf.

It warned that repeated delays to well plugging and abandonment work are “pushing up the estimated bill for decommissioning on the UK Continental Shelf”, together with competition for rigs from overseas and cost pressures.

The NSTA’s Decommissioning Benchmarking Report 2024 estimates that decommissioned costs totalled £2 billion in 2023. It said that industry knowledge sharing helped lower decommissioning cost estimates by £15 billion between 2017 and 2022.

According to that report, 71% of development wells were decommissioned as planned in 2023, but only a third (33%) of topside removals went ahead as planned, while only half of substructure removals took place as planned.

In 2023, 82 of the 109 planned platform development wells were decommissioned. Also, 40 of 62 planned subsea wells were removed, in addition to only two topsides of six, and four of eight substructures.

The UK had a goal to remove 1,300 planned platform wells by 2023, at an average rate of 140 a year, as well as 700 subsea development wells, 111 topsides, 112 substructures and eight floating production storage and offloading units.

“Pockets of operators continue to collaborate, perform admirably and deliver savings, but the majority need to improve by doubling down on their planning,” the NSTA said in July.

“Operators spent around £2bn on decommissioning last year, which was in line with forecasts, but they completed much less work than originally planned.”

The NSTA is spearheading a project to identify which wells on the continental shelf will be ready for decommissioning from 2026 to 2030 and to assess the supply chain capacity required to undertake the work.

It said that decommissioning is expected from 2023 to cost a total of £40 billion onwards in 2021 prices.

In the 2024 cost update, NSTA said: “The forecast cost of decommissioning from start of 2023 onwards is now £40bn in 2021 prices.

“A challenging economic environment for the industry and rapidly changing market conditions, driven in part by the global energy transition, have contributed to the increases seen in the past two years.”

Biodiversity

In addition to costs, arguments about biodiversity have slowed decommissioning. North Sea oil and gas production and associated pollution are among the biggest risk factors for biodiversity loss in the region.

The World Economic Forum estimates that half of all biodiversity loss is due to changes in land and sea usage, compared to 7% caused directly by pollution.

According to one scientific study published in Nature, oil rig designs can be future-proofed to protect biodiversity through reefing while there remains debate as to whether abandoning old rigs or removing them is the best option to promote biodiversity at old oil fields.

Several studies, such as the INSITE programme, are evaluating the impact of North Sea activities on biodiversity but so far evidence is inconclusive.

That programme concluded broadly that more evidence is needed to see how decommissioning impacts life in the North Sea.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by NSTA

© Supplied by NSTA © Supplied by Clarke Cooper/DCT

© Supplied by Clarke Cooper/DCT © Owen Humphreys/PA Wire

© Owen Humphreys/PA Wire © Supplied by Kath Flannery / DCT

© Supplied by Kath Flannery / DCT