Any business relies on its assets. Whether these are people, machinery, or even data, it is vital for the sustainable growth of any company that these are nurtured, protected and cared for.

None more so than in offshore operations. Shutdowns and any slowing of production can be significantly damaging, and costly.

Ever since we launched our diving medic cover to the energy sector in 1977, we have seen major shifts in attitudes towards subsea maintenance and repair.

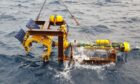

Major incidents across the globe have highlighted the need for more frequent and considered maintenance of equipment where the eye can’t see. Technology has evolved, as you’d expect, and we now see a multitude of remotely-operated vehicles (ROVs) which can detect and repair underwater equipment and machinery on the most complex subsea rigs and platforms, but not all.

Despite the advancement of technology, humans are still needed for areas that machines can’t reach, mostly underwater.

Experienced subsea divers are a rare breed. They are required for a wide spectrum of operations, ranging from changing valves and replacing blowout protectors, right the way through to helping place new installations.

The dangers are vast and the injuries they can sustain can be serious.

In the past year alone, our medics have looked after 115 divers, two thirds within the UKCS, the others in the US, Africa, UAE, Asia and one off the coast of Alaska, with everything from ear infections to barracuda and lionfish bites and appendicitis.

We predominantly look after saturation divers working from diving support vessels (DSVs)spending up to 28 days at a time under pressure travelling to their work site by diving bell.

It is a testament to the current safety record of the diving industry that, of the 115 divers, only eight cases related to an accident or an injury – including the two fish bites and an injury in a bunk in the saturation chamber, and only one resulted in the diver being a non-emergency disembarkation.

A significant change to the statistics from the 1980s, where in a five-year period there were 45 diving- related deaths in the North Sea alone.

The complications of incidents are vast. For example, recently, a DSV was operating in the UKCS, replacing a major pump on the sea bed adjacent to an offshore installation at a depth of 140 metres.

Divers living in the saturation chambers on the DSV were travelling to the sea bed in a diving bell.

One diver, on his first saturation dive, developed a rare complication, a burst lung in this case resulting in a pneumomediastinum, where breathing gas had leaked from his lung into the area around his heart and into his neck.

In a challenging environment, the Iqarus team had to maintain patient stability while working underwater and, at the same time, ensuring that the best medical care was offered to save the life of the patient.

The team mobilised a diving doctor, able to work in the chamber at pressure, to the DSV with the recommended Diving Medical Advisory Committee (DMAC) equipment.

With support from one of our diving medical specialists onshore, this doctor advised the DSV on the care of the diver and conduct of the decompression, ensuring that the diver was brought back safely to the surface with minimal delay and no adverse effects.

This example isn’t unique. Working in an offshore environment not only tests both the mental and physical stamina of employees but also the ability of support personnel to function under extremely harsh working conditions.

The dangers are real and apparent. The wellbeing of these divers is business critical. Their presence has a direct impact on the running of an installation.

An integrated and specialist diving, topside and medical service can bring together these safeguards in the

best interests of the people and the asset.

As the industry develops and looks at new technologies to enhance the diving environment and considers even deeper dives, progressive businesses need to ensure that their duty of care goes deeper too.

Dr Stuart Scott is medical director, Iqarus

Recommended for you