On April 7, Hurricane said its latest estimate for Lancaster field reserves had been upgraded threefold to just shy of 600million barrels based on a predicted 25% recovery factor.

UK mainstream media grabbed onto that, declaring that the West of Shetland asset’s overall reserves had passed the 2billion mark.

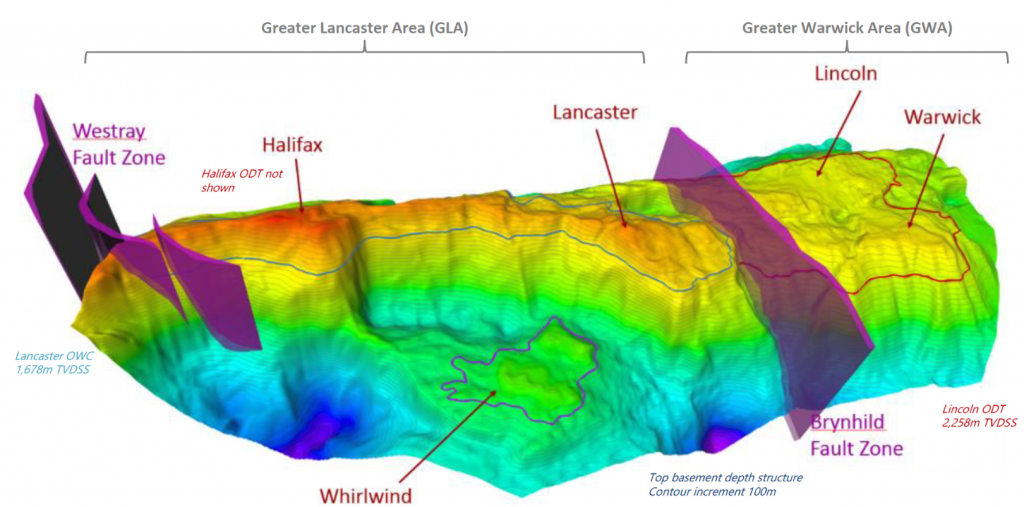

The fourth, Halifax, had been declared just days earlier on March 27; not only did it appear to be a huge find, it appeared to be geologically linked to the first discovery 35km distant, as prognosed, namely Lancaster.

Add to all this stock market investor boards chit-chat speculating that Hurricane might even have discovered at least 8billion barrels with its four exploration successes … Lancaster and Halifax, Lincoln and Whirlwind … and we have exciting times on the UK Atlantic Frontier.

In this exclusive, Hurricane’s CEO Dr Robert Trice summarises progress to date, paying particular attention to the results of freshly completed Halifax and the next steps with Lancaster where an early produuction system will be installed in 2019. Critically with Lancaster, Trice and his team can get on with raising the funding needed for the EPS and to ensure first oil from the two wells drilled so far gets to market ASAP.

“We have successfully drilled two horizontal wells (wells 6 and 7z), which we have already demonstrated to the Market … flow at high rates with very low draw-down and they’re ready to produce,” he said.

“What we’re doing this year is talking to the industry. We’re also looking independently at how we would finance it ourselves because the industry may not move fast enough or may not be interested. But we are looking to fund the EPS.

“In fact the industry is very, very interested and I must say that attitudes have changed dramatically with the results from Lincoln and results of the ‘four’ well.

“There appears to be general acceptance that there is a large oil column at Lancaster and there is oil beyond the Lancaster boundary. The potential of producing water is low to zero. That is the scientific view.

“Regarding EPS fundraising, our target is to have the money raised this summer so that we will be in a position to make the augmentations to the vessel … but no material modifications to the topsides.

“The reason why we think we have a good chance of doing this quickly and without delays is that the FPSO it was last used for producing oil of a similar nature to Hurricane’s. The API is 38 degrees; its high quality oil with relatively low sulphur content. Financially it’s equivalent to Brent.

“The EPS is seen as a very low risk investment to establish the big prize. We wish to raise $450million to be up and running by 2019. That’s not much and it will quickly become a cash generator. Currently we’re on track.”

When Energy met up with Trice, he could barely contain his excitement.

Bear in mind that he possibly knows more about basement geology than anyone else, was bursting with excitement, having been aboard the rig Transocean Spitsbergen for the closing stages of the Halifax well operations when the decision to drill deeper than originally planned was taken in lieu of the intended drill-stem test. A hydrocarbon column of more than 1,000m was encountered with no sign of oil:water contact.

The DST had been intended to measure reservoir pressure and bring oil to surface. That was its purpose. It was never designed to achieve a commercial flow-rate. It would have helped reinforce the belief that Halifax and Lancaster are one reservoir.

So what were the signals from the well that gave Trice the confidence to say what you have?

“We’ve got a mass of core data. Although we didn’t bring oil to surface we got pressures and those are being evaluated along with the wireline logs.”

So why can we say we believe the well supports our model?

“The first observation is that the well encountered an extensive oil column. If there was no connection between Lancaster and Halifax we would have expected there to be a shorter oil column. That would have taken the form of a local structural closure around Halifax and that would kill the model.

“The other piece is that the Lancaster and Halifax geology appears to be the same. Whilst drilling through the fractures, there was a familiarity about the way in which the drill-bit behaved. We saw the same drilling characteristics, gas chromatography, ROP (rate of penetration).

“But the real point is that when we look at the Rona Ridge from Lancaster to Halifax (Greater Lancaster) … the whole thing is fractured … faulted. Every 100m you’ve got some large feature and that’s the point. That is reservoir.

“We cannot see anything that cuts the ridge that would be a clear barrier. Now, between Lancaster and Lincoln, we can. And that fault runs all the way to Faroe. It is called the Brynhild Fault Zone.

“It clearly offsets Lancaster and Lincoln because we have a much deeper oil column at Lincoln than Lancaster. That’s a barrier; no argument. We see a similar fault at the end of Halifax … at the end of our segment of the Rona Ridge called the Westray Fault, which we believe segregates Halifax from the ridge that runs all the way up to Clair.

“But we cannot see anything of that nature between Lancaster and Halifax. Our observations support our model that it’s a single entity.”

Out of curiosity, from the publicly available geo-knowledge of the Rona Ridge sector, is there any evidence of similar significant barrier between the one the Hurricane team now knows exists between its acreage and the next bit of the Rona Ridge? According to Trice the answer is yes; there are indeed lineaments (distinct features) between Clair and the top end of Hurricane’s acreage.

Sometimes, news gets skewed and it did with Halifax. Speculation was of a billion barrels find; Hurricane did not publish an estimate.

Trice: “We’ve not said a billion barrels; I’d like to make that very clear. Whoever said that, I think they took the original (Lancaster) CPR (competent person’s report), they’ve looked at the oil-water contacts and assumptions that we used in that original CPR, then applied our new understanding of Lancaster and then come up with a number.

“I’m not being evasive. But what I can say is that we have publicly stated that a (revised) CPR for Lancaster will be available shortly. (It had not appeared as Energy went to print). Later in the year we will have another CPR covering all of our assets.”

This is for the armchair oilman: OK, the Halifax well is 35km from the Lancaster wells, and Hurricane is talking of an oil column of more than 1km depth, but how wide is that fairway?

People have been trying to compare Lancaster to Brent and Forties and have been trying to work out some sort of a volume for the discovery.

And, is Trice convinced that Hurricane actually has located the UK equivalent of Norway’s latest giant, Johan Sverdrup, which is now being developed?

“Here’s what I can say. Johan Sverdrup was the first time in Norway where they woke to the fact that the basement there was permeable and therefore was potentially a reservoir. So, yes.

“There’s a clastic wedge on top, which is the primary reservoir but they drilled into the basement and they’ve got oil down there. What woke them up was that they couldn’t treat the basement as a seal.

“That was the big wake-up call for the Norwegians.

“I was at a conference two years ago in Norway where they take basement very seriously and Johan Sverdrup was presented. Numbers had been calculated … I think they’ve got a 100m column.

Now, that’s a massive area so it’s a big volume. It’s a material resource.”

Limited information about Johan Sverdrup is in the public domain, but a Master’s Degree thesis completed last year is quite revealing. Go find “The Petroleum Geochemistry of the Johan Sverdrup Field, Southern Utsira High, Norwegian North Sea” – A study of maturity, organofacies, reservoir filling and biodegradation, by Fredrik Wesenlund.

In the Halifax discovery statement, Hurricane explained why the decision to deepen the well was taken and why it was not possible to do the planned DST. So what’s the next step?

Trice: “We have a budget; we go to our shareholders and we raise some money to do the job. Let’s say we have £5. We then say that £2 of that is for a DST. When we drilled to our planned TD, we were still in oil but had expected to be in water. So we have a dilemma. This is good news that we have a much bigger oil column than we expected.”

So how deep an oil column did he expect?

“Basically the same as Lancaster (600-700m). We anticipated a flat contact. That’s what we modelled on. We had three models … flat contact, tilted contact and something we couldn’t possibly imagine … a stratigraphic trap.

“When we reached TD (total depth), which is what we had budgeted for and then carried out testing, we were faced with the question: ‘What do we do? Do we extend testing, do we limit testing or do we drill on.’

“We had some weather that contributed to lost-time, we weren’t able to clean the well and so we had the choice … offshore and in real-time watching storms coming in, watching budget going down … ‘Do we spend another two or three days trying to lift the well or do we drill on?’

“We drilled on. We thought, we have real reservoir here, a hydrocarbon column, it’s better to know more about the geology, more about the fracture system.

“If we had used all our budget to clean-up the well and get some oil to surface, we may have run out of budget and wouldn’t have been able to wireline log, wouldn’t have been able to core.

“So we made the decision to deepen the well, undertake a full wireline programme … and I’m encouraged by what I have seen.

“And we have suspended the well to give us two straightforward options at some future date.

“One … go back and re-test and in order to do that we’ll have to find a way to clean-up the well. As an example we could go in with coiled tubing and lift the well from the bottom rather than suck from the top.

“We talked about doing that for the original well-plan but then thought it to be too costly; deployment of the equipment is time consuming during winter months so we decided not to do coiled tubing originally. So it may be that that’s an option.

“We also have the option to do that AND deepen the well; to find out definitively where the oil/water contact is.”

But Trice made it clear that returning to Halifax was not on this year.

“To go back we need to have first fully evaluated the data from this well and that’s going to take at least six months. And the reason that it’s going to take so long is because we have lots of core.

That core’s to go through the lab for a whole variety of measurements and that, integrated with the wireline data will give us the best understanding.

“Q1 into Q2 next year would be an ideal time to go back. We would then also be completing the Lancaster wells for the EPS.”

Trice continued: “Halifax was our most ambitious well ever. We’re really excited by the results.

“We drilled for the first time in the UK a significant section of basement with a 12-1/4 inch bit; and we used a special kind of sheer-splitting fluid called Drillplex (viscosified brine), which prevents any losses whatsoever.

“The last thing one wants is to have total losses like we experienced on the (Lancaster) ‘seven’ well and then gas coming to surface. It was done for safety reasons.

“Basically it fills up the fractures, sets solid and keeps the gas and oil at bay. We used it on the first well on Lancaster.”

And so-forth.

Halifax is attracting huge attention, little wonder given the quality of the results, that it appears contiguous with Lancaster and that Hurricane is out pitching to money markets, to oil companies via its data-room, and getting on with pushing the EPS forward regardless of which financing options wins out.

Meanwhile and surprisingly, Trice is of the view that many have missed the significance of the Lincoln discovery made with the well drilled at the back end of last year, immediately prior to Halifax.

“The results came out during the week just before Christmas and the both journalists and the Market ignored them.

“And yet we had made a discovery that could equal Lancaster and may mean Lincoln and yet to be drilled Warwick are one big structure.

“We had found a different oil column to that at Lancaster. It’s a major discovery in its own right.

“If we’d not bothered with Halifax or Lancaster and instead drilled this one well last year it would have hit the news. But it got lost in Christmas and excitement of Halifax.”

Hurricane has quite literally opened up a new play that others like Arco and Shell missed decades earlier, even though they had touched basement with wells drilled.

As a result, Hurricane is apparently faced with an embarrassment of riches. Somehow this still small company has managed to, in a sense, embarrass the North Sea Establishment, embarrass the

Market; embarrass the mind-sets that are very alive in Aberdeen and London today and which by the look of it are going to change the game.

Trice: “What I can say is that mind-sets have changed and we’re seeing that through re-engagement of the majors. There has been a paradigm shift.

“There was a model (for WoS) and somebody came along and broke it. Some people find that painful. I don’t.

“There’s no ego in this; the science … the data … tells you what’s there and we believe that, for UK waters, any basement next to Kimmeridge clay not to behave like other

basements around the world is ludicrous.

“What science could you possibly apply to say that Scottish granite is different to granite in Africa or America or Vietnam? It’s granite! And it’s fractured.

“If you’ve got enough fractures and you have a nice source rock … and we’ve got world-class source rock … why shouldn’t it work?

“Often we get push-back about basement reservoirs watering out. My challenge (to those who claim this) is name one; just one, anywhere.

“And when you’ve named that one field that watered out, is Hurricane intending to apply the same technology to cause the same watering out?

“Vietnam’s been producing oil for decades … over a billion barrels and it hasn’t watered-out yet.

“Zeit Bay (Egypt) has been producing since the 1960s and hasn’t watered out.

“Augila-Nafoora in Libya hasn’t watered out and La Paz in South America has been producing from basement since at least the 1930s and hasn’t watered out.

“However, I know of one example that did water out. That was Dongshengpu in China where they basically raped the field. It watered out; they went away and thought about it. It recovered and that’s now producing dry oil.

“So, I’d like to know of one basement reservoir that’s watered out, because I can’t find it.

“I’m not saying that I know everything about basement; my point is that maybe there are one or two I don’t know about.”

Recommended for you