In the wake of the Piper Alpha disaster, A&E consultant Graham Page had braced himself for an onslaught of arrivals ferrying survivors.

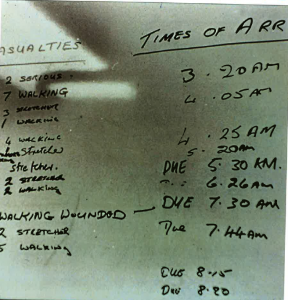

A board listing helicopter arrivals had been set up in an office at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary (ARI) to help staff keep track.

But by 7:45am, it showed that just two more flights were scheduled to land − at 8.15am and 8.20am.

A colleague asked why the list hadn’t been updated, only to be told that no more helicopters were expected.

It was then that staff realised the true extent of causalities for that fateful night.

Professor Page said: “There was a general feeling of horror about the whole situation.”

“It’s always distressing to see badly burned people, but the realisation that no one else would come in only came very gradually.

“But we didn’t step down or assume that that was everyone who was coming in. We still nurtured hopes of people coming ashore in a boat.”

The first explosion on Piper Alpha occurred at about 10pm.

More than five hours later the first helicopter arrived carrying just two seriously injured workers.

“The general rule in a major accident is you take the most seriously injured first,” Prof Page said.

“That does not work in an offshore situation because helicopters will take two or three stretchers, then you fill the gaps with the walking wounded.

“The first casualties came in at 3:20am.”

Prof Page said the night and the days that followed were a steep learning curve.

His involvement started while watching the 10 o’clock news. The presenters had just said goodnight, when there was another late item about an explosion on an offshore installation.

The coastguard was able to tell Prof Page something had happened, but because communication equipment on Piper Alpha had been damaged in the blast, it was not possible to get a full picture.

Prof Page knew, however, that the situation was serious enough to warrant declaring a major incident.

He was responsible for getting all of the chief ARI medical staff in place to deal with the situation.

Prof Page said: “The thing that always goes wrong in major incidents is that communication always falls down. People don’t communicate properly.

“People assume they know what’s happening, when they don’t know.”

At ARI, the team was well trained and well marshalled.

The medical director and senior nurse set up a control room and went about calculating how many beds were available.

They then started clearing beds, sending home people who were deemed fit enough, though at that stage they still had no clear indication of casualty numbers.

The duty A&E consultant and senior nurse assembled as many of their own staff members as possible.

“It’s important to get your own medical staff in, because in an emergency, staff function in an environment they know,” Prof Page said.

“If you bring people into a strange environment they do not function well.”

The nature of the incident meant plastic surgeons would also be needed to carry out skin grafts.

It helped that a large number of plastic surgeons were in Leicester attending a conference, meaning about eight could be flown to Aberdeen, where they attended to badly burned casualties.

While arrangements for treating casualties were being made, another important operation was taking place to keep a lid on rumblings outside the hospital.

Police were responsible for notifying next of kin, but a large number of journalists had gathered outside the hospital in search of information.

“We were the centre of the world for a few days,” Prof Page said. “The media side has to be expertly handled to get a balance between public interest and intrusion.”

Prof Page said Alan Reid, then-communications-director for NHS Grampian, played a vital role in that regard.

Mr Reid said he tried to provide updates every 30 minutes to keep the reporters up to speed and stop them trying to gain access.

Accommodating VIPs was another plate the team had to keep spinning.

Word filtered through to Mr Reid that Margaret Thatcher had cleared her diary and would visit.

He soon found out that Prince Charles and Lady Diana would come to the hospital as well.

Prof Page said: “If the VIPs come too soon they’re seen as being a nuisance, but if they don’t come they’re accused of being uncaring.

“The public has the idea that the Prime Minister should be there immediately.

“But they would just divert police and security resources at a time when they’re working at full pelt, so good judgement is needed.”

Mr Reid said: “By Friday night we had decided that we had to get the hospital back to being a hospital.

“I only issued one press release the whole time and that was to thank people.”

Recommended for you