From the grey and wind-scraped coast of The Black Isle, Sue Jane Taylor watched with a child’s eyes as two metal and wrought iron monsters appeared before her, yawing against the full force of the North Sea.

Whether she knew it then or not, these colossal structures – the emerging Nigg and Ardersier oil platforms – would become forever immortalised in her mind.

Over the last 20 years, she has focused on showing the world the hidden beauty of life offshore – but perhaps more importantly, the people behind the industry that has buoyed the north and north-east.

Ms Taylor has spent months on various oil rigs, sketching the teams at work and the imposing structures which she remembers so clearly from her childhood. Most poignantly, she spent time on the Piper Alpha the year before the blast that killed 167.

Determined to humanise the disaster and shift the focus from the body count to the people who perished, Ms Taylor put together her work for part of a new exhibition, Oil Workers, Scotland. But it was pulled amid concerns about creating negative publicity around the disaster.

However, the determined artist met families in Aberdeen who were adamant they wanted her to continue.

And two years later, she was commissioned to create the Piper Alpha Memorial at Hazlehead Park, Aberdeen.

Ms Taylor, of Dornoch, said last night that her time spent on the doomed rig has stayed with her over the last 29 years.

“That was my first stay on a platform longer term,” she said. “I got to know the people and experience what it was like living on an oil platform. It was an incredible experience, the crew were very friendly. That visit was very inspirational. Little did I know that a year later some of the men I met would perish in the disaster.

“The impact of that was quite extraordinary. Being offshore is surreal anyway – it’s not a real world. It’s an artificial environment within these giant metal islands. To know that these guys suffered so much, and that 167 died, is painful.

After being asked to halt the Oil Workers, Scotland exhibition plans in Edinburgh, Ms Taylor travelled to the north-east to meet the families of those who died to be allowed to honour their memory.

With their approval, she spent more than a year locked in a large draughty shed in Lumsden creating the three-figure sculpture, which now stands in rose garden at Hazlehead Park.

She said: “One of the survivors, Bill Barron, posed for the central figure in the sculpture. It was a very intense period, but I tried to separate myself away as much as I could from the emotional and political things going on because it was a massive struggle for these families to get the money for the memorial.”

It was a far cry from standing watching the rigs with her family back home in the Highlands.

After leaving school, Ms Taylor studied at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen where she could never have imagined what was in store.

“As an art school student in Aberdeen in the 80s, it was a boom town – a boom city – very separate from my own life,” she said. “We saw the oil industry as kind of alien, a parallel world.”

But those worlds collided when Ms Taylor was given the chance to visit a service platform, which then led to a trip to a much larger platform in the BP Forties field at the age of just 24.

Fresh from a scholarship in Sweden, the young artist jumped at the chance and was met with biblical weather, rolling seas and an all-male staff barking and growling at each other as they worked the rig.

Rather than flag in this male-dominated environment, Ms Taylor positively leaned into the wind, documenting everything and sharpening her artistic eye on the raw, unrefined, man-made beauty of these structures.

She said: “I was woken up in the middle of the night and was taken out on the deck. Just watching these guys moving on the deck, manoeuvring all these containers, loading, unloading with the crane above was just an incredible experience for me. It blew my mind. Really that was the start of it all… not knowing I’d be working on it for nearly 30 years.”

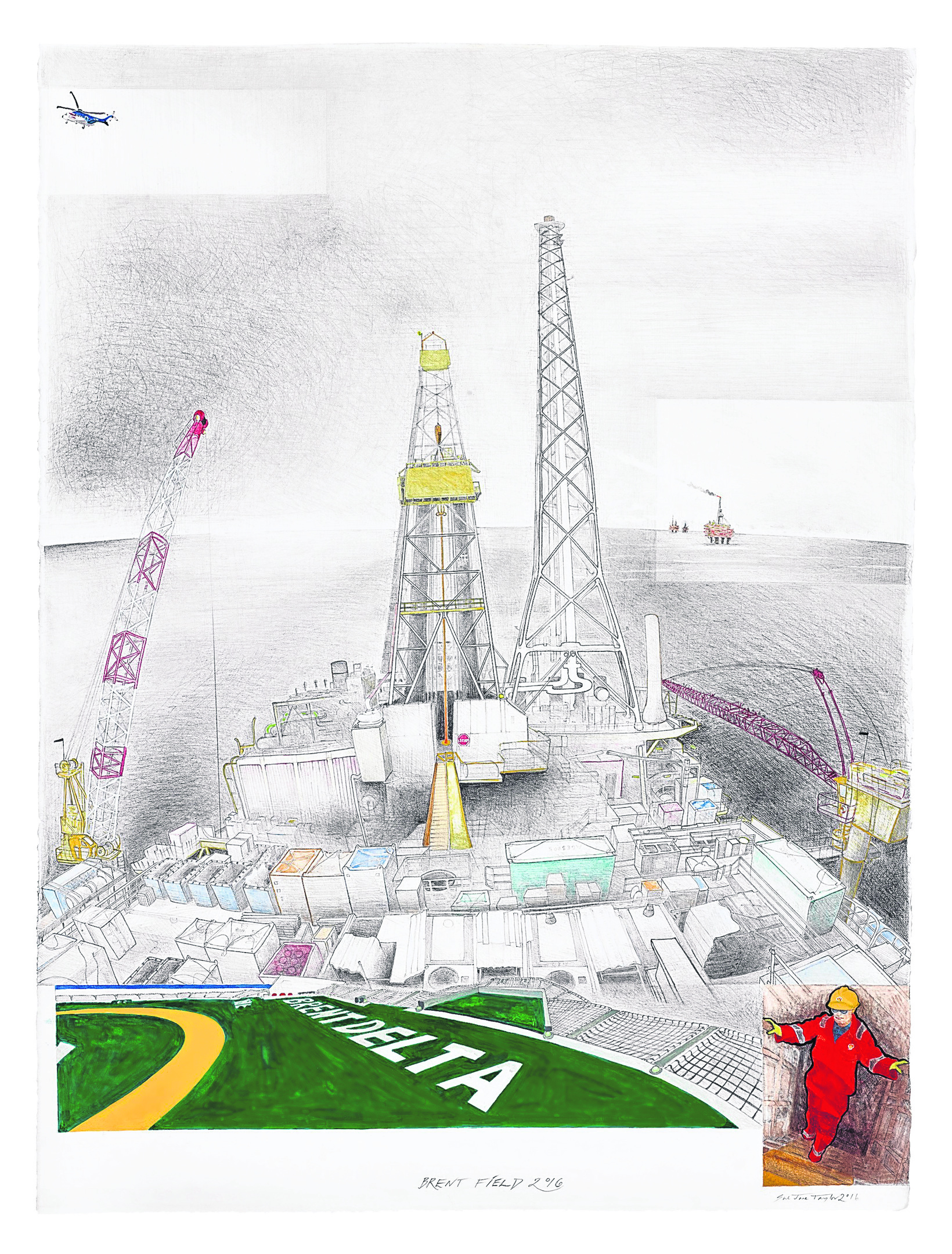

And nearly 35 years on since her first visit to a North Sea structure, Ms Taylor is still visiting them to gain inspiration for her work. In 2014, it was three visits to The Murchison Field and in 2016 she made a trip out to The Brent Field visiting both the Delta and Bravo platforms.

She said: “I didn’t expect to go offshore again, I thought that was it. But I got to go to Piper B in 2004, then the chance came up at Merchison in 2014, and Shell had a final farewell for the people who worked on Brent Bravo and Delta throughout the years. That was incredible to see that huge topside in docks, the first lift by Pioneering Spirit ship. It was almost like an alien ship had landed. That was an amazing experience.”

These visits have helped inspire her latest exhibition, Age of Oil, which includes her own personal insights and those of her subjects. It is currently on show in Edinburgh, but will arrive in the Granite City early next year.

The multimedia exhibition considers the future of energy in Scotland and the challenges of removing a structure the size of the Eiffel Tower – the Brent platform- from the middle of the North Sea from Ms Taylor’s perspective.

One of the other 17 pieces of artwork is an eye-catching view of Aberdeen harbour, where the colourful supply vessels dock before heading to the rigs.

The exhibition also includes diary extracts from her time offshore.

She has also written a book to accompany the exhibition, pulling together art, environment and industry while revealing a relatively alien way of life on board a North Sea oil platform, while also considering the future of energy in Scotland.

As well as looking back over the years, Ms Taylor’s work has also focused on the future. In 2013, she focused on the ground-breaking Beatrice Offshore Wind Farm, off the coast of Caithness for an exhibition.

The £2.6billion 84-turbine wind farm is expected to be complete by 2019, and will power 450,000 homes.

In 2013, Ms Taylor focused on renewables for another exhibition in Aberdeen, with paintings, etchings, drawings and diaries which documenting the project.

It is often said that artists are in a constant state of discovery. Yet in terms of why Ms Taylor keeps returning to the motifs of the North Sea and the oil and gas industry, she is sure of her answer.

“As a visual artist it’s very exciting to draw and record these incredible massive structures alongside the setting that they’re in – the extreme environment. Also, being on a platform; very few outsiders get a chance to see that.”

She is also acutely aware of the effect oil has had on the north-east, and how intrinsically linked the two have become.

When oil does well in the north-east, the region does well, Ms Taylor said. But she admitted that it is what goes on in a downturn, like just now, that is most interesting to someone with her artistic bent. She views it as a privilege to have been given almost unfettered access to the industry, in the good times and the bad.

She said: “Elsewhere in the UK, not a lot of people know what goes on here. About 90% of everything we do relates to oil. It still dominates our society. It’s made such an impact economically that to see it from an artist’s eye brings a more human side to the industry, the people’s side.

“The oil industry is a huge corporate giant and they have a lot of control of their PR and imagery. The corporate imagery dominates photography and the impressive technology, but in the past the people had been forgotten – the workers. It’s great to document such an eclectic group of people who work on a platform in a claustrophobic social environment. It’s almost like getting a look into a secret world.”

Sue Jane Taylor’s Age of Oil is on show at the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh until November 5. It comes to Aberdeen University’s Sir Duncan Rice Library from March-July next year.

Recommended for you