As crude oil gushes out of the U.S. like never before, it looks increasingly like North Sea oil will suffer collateral damage.

America exported a record high 1.98 million barrels a day of crude in the week ended Sept. 29, equal to the crude that normally gets shipped every day in the North Sea. Much of the U.S. outflow is going to Asia, which has become increasingly important in recent years in determining North Sea oil prices, effectively sandwiching Brent crude between bearish forces.

“It’s direct competition to North Sea production on many different fronts,” said Olivier Jakob, managing director at Petromatrix GmbH in Zug, Switzerland. Where U.S. exports go to Asia, “it will be more difficult for the North Sea to push some of its barrels outside of the region. It creates competition. It’s going to be a bearish factor for the North Sea market.”

The impact of rising American oil shipments on Brent — for many in the industry the most important crude benchmark — shows the increasingly disruptive force of U.S. crude in international markets. Washington in late 2015 lifted a 40-year ban on most oil exports, in the process reshaping the world’s energy map with U.S. crude being sent by trading houses such as Vitol Group and Trafigura Group to faraway locations including Switzerland, China and Israel. The U.S. export restrictions were imposed in the aftermath of the 1973-74 oil crisis.

U.S. producers ship barrels directly to refineries in Europe, placing the cargoes in competition with North Sea supply. At the same time, they’re sending a growing share to the prized Asian market. Refineries in China and South Korea in particular have become a critical source of demand for North Sea oil in recent years, helping to clear any oversupply out of the European market.

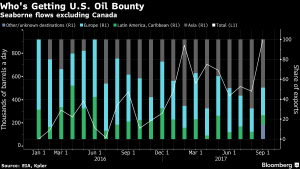

Of the flood of crude exported by the U.S. late last month, more than half went to East Asia and nearly a third was shipped to Northwest Europe and the Mediterranean region, according to a trader who’s monitoring the region’s exports. The remainder was shipped to the Caribbean and Latin America, the trader said. That’s in line with exports so far this year, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration and Kpler, a company that monitors ship movements.

The size of the U.S. exports — which has jumped from 25,000 barrels a day a decade ago to nearly 2 million barrels a day now — is now rivaling those from the North Sea. As a whole, North Sea flows have averaged 1.98 million barrels a day this year, according to loading programs compiled by Bloomberg. The flow of the key four regional crude streams — Brent, Forties, Oseberg and Ekofisk, which largely set the price of the benchmark — will run at about 820,000 barrels a day in November.

Widening Spread

U.S. crude has become increasingly attractive to foreign buyers in recent months due to the widening discount of West Texas Intermediate crude to Brent, the global benchmark. The spread started to expand in late July amid a tightening market for Brent and then ballooned in late August amid Hurricane Harvey. It reached $5.99 a barrel in intraday trading on Tuesday, remaining near its widest level in two years.

The exports surge has coincided with WTI becoming more of an international crude. Trading during Asian hours has risen sharply this year and stood at 18 percent of all activity in the third quarter, according to Owain Johnson, head of the energy research and product development team at CME Group Inc.

It’s not just the relative cheapness of WTI that’s hurting North Sea prices. Margins from turning crude into fuels are also sliding, creating downward pressure on Brent, according to Florian Thaler, an oil strategist at Signal Ocean. So-called hydroskimming margins, one of the simpler processes by which refineries can make fuels, fell to $3.15 a barrel on Oct. 9 for North Sea oil, data from Oil Analytics show. That’s down by more than 50 percent from the start of September, when Harvey temporarily slashed a quarter of U.S. processing capacity.

Slow Clearance

Added to that, U.S. exports are “clearly not helping the sweet-crude picture either,” with Brent-priced West African oil taking longer than normal to find buyers to Asia, Thaler said. Along with margins, that means prices for crudes with lower sulfur content in the Atlantic Basin are “a bit under pressure.”

Physical North Sea oil trades at differentials to regional benchmarks, and in late September, Forties was at three-year highs to its yardstick. Hurricane-related disruptions in the U.S. Gulf, which have now abated, originally helped to account for the high differentials, according to Petromatrix’s Jakob. Forties slipped to parity on Oct. 2 and other prices have been around that level in recent days.

“Two forces are at work” in weakening North Sea oil prices, said Eugene Lindell, an analyst at JBC Energy GmbH in Vienna. “Arbitrage inflows of U.S. crude into Europe are weighing” while WTI-priced crude is growing in appeal the world over due to its relative cheapness to Brent.

Recommended for you