At a time when the UK North Sea is crying out for new exploration, investment firm Reabold Resources believes it has found a fresh approach that can get drill bits spinning again.

The London-headquartered business invests in undervalued, low-risk, near-term upstream oil and gas projects which have stalled.

The market dislocation caused by the downturn means those opportunities are available.

It also identifies a clear exit plan before it puts in money.

In the North Sea, the company’s bosses have backed an asset operator, rather than directly buying stakes in offshore licences.

Reabold invested £2.5 million in exchange for a 32.9% interest in Corallian Energy, which has stakes in a number of North Sea assets, including Colter, Oulton and Wick.

Corallian acquired a number of UK continental shelf licences in 2015, but, against the backdrop of the oil industry downturn, making progress was extremely difficult.

But Reabold’s announcement in November 2017 regarding its initial investment in Corallian got the ball rolling.

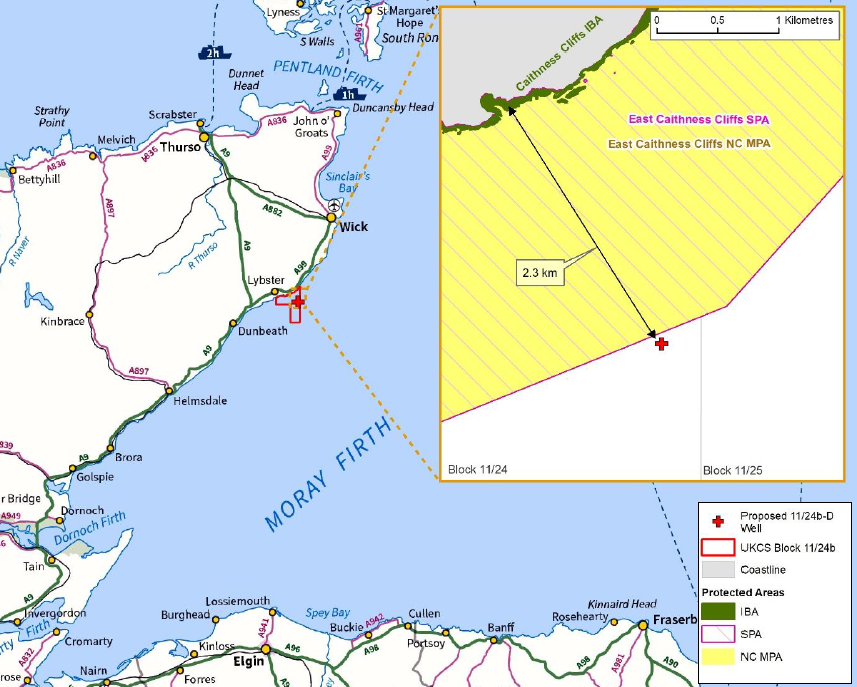

Multiple farm-outs were agreed for Corallian’s most promising assets within a short space of time. At the end of November, Upland Resources agreed to buy 40% of licence P2235, which contains the Wick Prospect, in the Moray Firth.

In February, Baron Oil and Gas entered into an option agreement with Corfe Energy to buy part of its stake in the same licence.

Licence P1918 containing Colter Prospect in Bournemouth Bay also attracted firm interest.

In January, United Oil and Gas struck a deal to acquire 10% of the asset, while Baron appeared again in March, when it moved for a 5% stake.

An exploration well is scheduled to be drilled at Wick in September, with the Colter well following in the fourth quarter.

Reabold co-chief executives Stephen Williams and Sachin Oza think it is no coincidence that the flurry of deals came about so soon after they arrived on the scene.

They said Reabold facilitated funding for projects that have been overlooked for different reasons, as well as helping operators come up with clear plans to move forward.

They also said Reabold’s approach was “counter-cyclical”, meaning it strives to make progress with near-term drilling activity when rates are deflated.

“We want to move forward when costs are low,” Mr Oza said. “We do not want to chase the cycle, like industry usually does.”

The business partners said their backgrounds in asset management had helped them identify the right projects and make good choices.

Investors tend to shy away when a sector is in free-fall. It means that when they come back, they have to start building up their knowledge of projects from scratch. But Reabold’s bosses stuck with it.

Mr Williams said: “The farm-ins show that companies were interested, but they needed a catalyst. We’ve invested and now other companies have come in behind us.

“We’ve targeted good quality projects which have been stranded. They were not moving forward because there was not enough available capital to take things forward.

“A lot of good work has been done to de-risk projects, but what has been missing is the capital, as well as a more commercial approach.

“We leverage the work that has already been done and the capital already spent to demonstrate the value of upstream assets and bring in critical funding.”

Convincing investors to put money into upstream oil and gas is difficult, partly due to a loss of trust.

Mr Oza said it became almost impossible for investors to tell the difference between a good project and a bad project in recent years. As such, many good ones went by the wayside.

He said good projects were characterised by the presence of high-quality geology and subsurface data, as well as being close to existing infrastructure.

Mr Oza also said it was vital to get the business plan right.

This gives investors and partners a clear line of sight towards monetisation.

He acknowledged that smaller companies have been trying to raise capital to take projects forward, but the results are not always desirable.

Some issue new shares, thereby diluting the value of their existing ones, and generally ticking off investors.

Others sit on their hands and try to ride out the cycle. Unfortunately, the length of the downturn means these companies have eaten through their cash balances, and do not now have enough money to act.

Mr Oza said: “We find the operating company, give them a business plan and rather than being seen as a competitor we are seen as a welcome investor, helping them take the asset forward.”

In the months to come, Reabold will be targeting further investments, as it rolls out its strategy across additional transformational projects, buoyed by higher commodity prices and lower costs.