On a sunny October morning, members of the The Geological Society pack an ornate lecture theater at their imposing headquarters on London’s Piccadilly. One of their number introduces a scientist who “needs no introduction,” the man people had come to see.

Taking to the podium, Dr. Robert Trice, a lifelong rock obsessive who’s also chief executive officer of independent oil company Hurricane Energy Plc, adjusts his glasses and shakes his mop of pale hair. Then he explains his billion-dollar idea.

From inside a ship, sloshing around the 65-foot waves off the coast of the Scottish isles, he plans to poke a diamond-tipped drill-bit into the sea bed. He’ll take it past layers of once-oil-soaked sandstone rocks straight into a strata of solid granite — what geologists call the basement. Then the drill will turn sideways and hopefully intersect a bunch of naturally formed cracks. If his science is correct, there will be enough oil pooled in those cracks to make him a very rich man.

For more than a decade, people in the industry have excoriated his idea for being too expensive, too technically challenging and even geologically ridiculous.

“I’ve stopped arguing with them,” he said over lunch the day before his speech, sipping on a glass of red wine. “They’ll see.”

Trice, 57, a geology PhD who’s worked in the oil industry for three decades and founded Hurricane in his garden shed in 2005, likes to compare himself to another maverick who went from voice in the wilderness to billionaire prophet: George Mitchell, the father of shale drilling.

Mitchell started experimenting with the idea of hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” into shale rock in the 1980s. It took thousands of wells and 30 years for the American oil industry to widely adopt the practices he pioneered. When it did, the U.S. became the largest fossil fuel producer on the planet, permanently altering the global energy trade. Mitchell died in 2013 at 94 with a $2 billion fortune.

While the granite under under the Atlantic Ocean west of the Shetland island isn’t likely to be another Permian, if Trice is right about the geology it will prove billions barrels of undrilled oil. Success would be a significant shot in the arm for Britain’s beleaguered oil industry, where drilling is at its lowest level since the birth of the North Sea in the 1970s.

“Fractured basement isn’t a myth,” said John Browne, the former chief executive officer of BP Plc, who spent part of his early career working in the North Sea. “But it’s difficult to drill.”

We’re about to get a clearer picture of how well it will work. A floating production vessel specially modified for harsh conditions is now sailing through the English Channel to the North Sea. In the first half of 2019, Hurricane plans to use it to produce from two wells. The test of a good result? Hurricane needs the pressure underground to stay as high as Trice’s models predict, showing the cracks in the granite are interlinked and the pooled crude can flow freely to the surface for a sustained period.

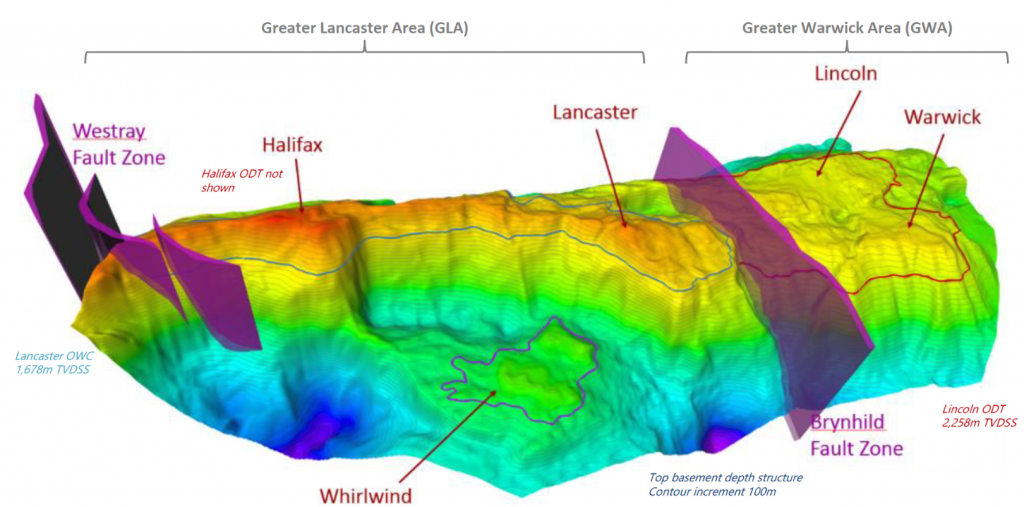

A report commissioned by Hurricane concludes one of its fields, called Lancaster, likely has half a billion barrels of recoverable oil. That’s worth almost $33 billion at $65 a barrel Brent crude, much of which would go to the British government in taxes. Hurricane is also exploring another two fields thought to hold billions of barrels more.

In scientific circles, Trice’s relentless push to unlock this treasure from the U.K.’s bedrock has made him a minor celebrity. During his October speech, one geologist in the crowd leaned to the edge of his seat as Trice spoke, quietly saying “yes!” each time the explanation of granite fractures became particularly exciting. Others remain skeptical.

“The productivity and longevity of that productivity is a concern” with fractured granite, said Ariel Flores, BP Plc’s president for the North Sea region. “There’s a lot of uncertainty and risk.”

The primary risk is in the rock. While sandstone is like a sponge, where fluids move about freely into a well that brings them to the surface, granite is like a piece of glass. Crack a pane of glass in two separate places, and you can pour tiny bits of oil inside each fracture, but those deposits can’t reach each other.

Trice’s plan depends on there being so many fractures crisscrossing one another throughout the granite, they have formed a sort of highway system for oil to travel through. Seismic imaging can provide hints such a network exists, but the image is fuzzy. The plan also relies on the hope that those fractures aren’t flushed with sea water as the oil is being produced, turning it into world’s most expensive well of undrinkable water.

“I can’t think of any example where someone has just set out to explore” granite, said Roy Kelly, managing director of Hurricane’s largest investor, Kerogen Capital. “Some people thought he was mad.”BP is now drilling into the more traditional sandstone near Hurricane’s blocks in the Scottish seas. It probably has a similar granite formation within the same area. Flores said he’s watching Hurricane’s progress closely and will probably drill its own basement development well in the next couple of years.

Trice spent the early part of his career at Enterprise Oil Plc, a U.K. driller acquired by Royal Dutch Shell Plc in 2002. When he proposed drilling in Atlantic granite, pointing to similarly successful work in Vietnam and Italy, Shell’s response was dismissive. Major oil companies, slow-moving, bureaucratic beasts, aren’t inclined to take risks on unproven geological ideas.

In 2004, Trice quit to create Hurricane. As he scrounged for capital, he found the financial industry was no easier to master. His initial investment came from an independently wealthy man in his hometown of Alton, England, who Trice met at the insistence of a taxi driver.

Hurricane’s first wells suggested oil was present, but investors needed to see if it could flow. In 2014, right as the price of crude was plummeting off a cliff, Trice drilled a kilometer-long horizontal appraisal well into the Lancaster prospect.

Almost 10,000 barrels a day spouted out of the well. That’s not spectacular, but it was encouraging enough to move forward. Later that year Hurricane raised 18 million pounds ($23 million) in an initial public offering, and issued convertible loan notes. It’s since expanded its initial exploration work, finding even more oil in the area surrounding Lancaster, and raised another $500 million to develop the Lancaster early production system.

In August, Centrica Plc-backed Spirit Energy has farmed into another two other Hurricane prospects called Lincoln and Warwick and agreed to pay for three exploration wells. Hurricane’s current market value is 831 million pounds ($1.1 billion) and Trice owns 1.3 percent.

Even after the discoveries Trice has made, he’ll need to produce oil sustainably to truly win over his critics. After his last big find two geoscience professors from Heriot-Watt University penned a blog post, outlining all the challenges facing Trice, titled: “Is Britain’s ‘largest oil discovery in decades’ all it’s cracked up to be?”

Though they found the idea “exciting” they pointed out that oil from the sort of reservoir Trice is targeting has been known to initially surge into a well, before rapidly petering out. And even if Hurricane can get all the crude to the surface, some of it may be so viscous and heavy it becomes uneconomical to produce.

Trice is undaunted, putting the odds the next Lancaster well will have a positive result at 100 percent.

“I basically saw this as a missing opportunity,” said Trice in a phone call in September. “The very simple philosophy is that if fractured basement works around the world why couldn’t it work in the U.K.?”