A pioneering new microbial technology which will soon be trialled in the UK North Sea could add decades to the basin’s lifespan, saving jobs and “kicking decommissioning down the track”.

A standard recovery rate from an oil reservoir is about 35%, with the rest staying stubbornly trapped in tight, difficult to reach pore spaces.

But oil companies could get after the remaining “stranded” reserves by “manipulating” microbes found naturally in the reservoir.

The technology’s developers claim they can reduce and, in some cases, reverse production decline in reservoirs, and revive shut-in wells.

It would also change the investment case for marginal fields that might otherwise be considered non-economic.

The prize is huge. It’s thought that 70% of UK North Sea wells have the right conditions for the technology to be applied. On a global scale, the “trapped oil market” is estimated to be worth $350 trillion.

Capturing even a very smaller percentage of that work would be a huge money-spinner.

The patented Organic Oil Recovery (OOR) process, developed by UK energy service firm Hunting and California-based business Titan Oil Recovery, ticks just about all the boxes.

The joint venture claims OOR has been “de-risked” to a large extent. More than 300 well tests have been conducted on 48 commercial oil fields on four continents.

The results are staggering: a 94% success rate and an average increase in production of 92%.

Tests will be carried out later this year on UK North Sea fields operated by some of the basin’s household names, in what has been billed as a “key six months” for the venture. OOR will also be piloted on 18 wells owned by one of the Middle East’s biggest producers.

It’s incredibly cheap and easy to apply using existing equipment. A pilot, which requires the injection of low volumes of a nutrient feed for the “resident” microbes, only costs around $50,000.

It’s also quick to deploy, which is important for those with cessation of production fast approaching.

Chris Venske, engineering and technical sales manager for OOR, said he had progressed from first conversation to pilot tests in six months with some operators.

Furthermore, OOR, which is the first technology to come through Hunting’s Tek-Hub in Badentoy, south of Aberdeen, has been found to reduce the production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

The gas is a real bugbear of oil companies. It sours wells, reduces oil production and increases corrosion on installations.

The bacteria which produces H2S is primarily fed by the injection of seawater in the North Sea.

Some companies spend tens of millions of pounds every year trying to suppress the production of H2S.

So a remedy will likely be of great interest to many companies, particularly those who rely heavily on water injection to enhance production from their wells.

Roger Findlay, OOR general manager, said the process should not be confused with microbial enhanced oil recovery (MEOR), which isn’t new.

Mr Findlay explained that OOR is about using the existing ecology of a reservoir – treating and manipulating resident microbes that are already downhole.

“Old” MEOR involves introducing foreign bacteria into a well and had a “mixed” track record.

Its drawbacks included the use of sugar-based nutrients which accelerated H2S production, with all of its associated pitfalls, and unsustainably high costs.

The OOR process involves identifying resident microbial life in oil reservoirs, then designing a unique nutrient package to feed them.

The nutrients are organic and biodegradable. Release them into the sea and they’d do no harm.

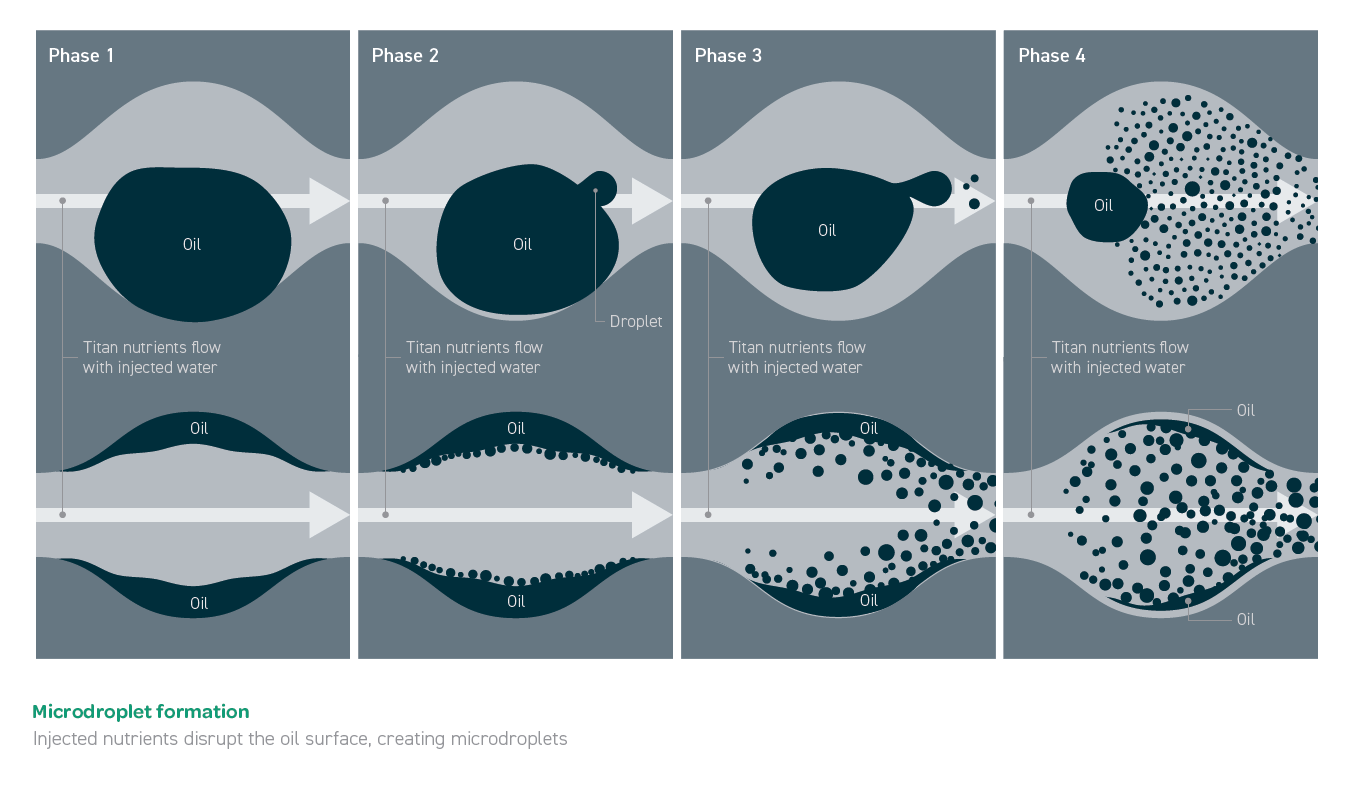

Feeding the microbes increases their numbers exponentially. They “plume”, automatically spreading throughout the reservoir, covering much more of the rock.

They are then starved, which causes them to evolve.

Mr Findlay explained: “The microbial life that’s down there wants to be in water. We are feeding them, increasing the population, then starving them so that we can increase the evolution of that microbial life to go from wanting to be in water to wanting to be out of the water.

“When they go through that process, the microbes move from the water towards the oil.

“When the microbe goes into the starvation state it looks for food. It looks for food around the oil droplet because it believes it’s much more likely to be nutrient rich there.

“The microbial life surrounds and changes the interfacial tension of the droplet, increasing the chances of the oil breaking into smaller droplets, which are more likely to be released from the pore spaces within a rock and a reservoir formation.”

The OOR application process is broken into steps, starting with a field screening of the reservoir characteristics.

The “sweet spot” at which OOR will work is quite large. A reservoir temperature of less than 95 degrees Celsius is preferred, but is not a deal breaker.

Water pH of between six and eight, and oil gravity from 16-42 API also help create the right conditions.

Laboratory analysis of small samples of water produced from the well are then carried out to determine the type of microbial life found in the well. The right nutrient package can then be designed.

The third stage is the pilot, which, if successful, is followed by a “targeted water flood implementation”.

It’s essentially a scale-up of the pilot, with larger volumes of the nutrient injected.

The final stage is a full-field application.

Bruce Ferguson, managing director at Hunting Energy Services, said the joint venture could scale up OOR “really quickly” to cope with the demand they hope to generate.

Mr Ferguson is confident OOR will be “value enhancing” for Hunting and is encouraged by the level of interest received from major North Sea operators, particularly those who have signed up for pilots.

Operators are often risk averse and sceptical when it comes to adopting new technology, engaging in a race to finish second.

Hunting has come up against that cautious attitude when discussing OOR with a number of operators, but Mr Ferguson understands why potential clients seek assurance, with multi-million-pound assets at stake.

He said: “It’s interesting to see the different cultures of operators. Some are creating safe environments and will innovate and bring through technology.

“But others who you think would be receptive, say, ‘no, it’s snake oil’, or ‘it’s too good to be true’.

“Sometimes it’s as simple as that – there’s no science behind their reasoning.

“That’s why we have to prove up OOR through field trials, and that’s fine. That’s the nature of the beast,” he added.

Mr Venske spoke to four or five operators who were interested, but said “point blank” that they were “not going first” and were waiting for the results of the upcoming North Sea trials.

Hunting is confident that OOR has already been commercially and technically de-risked.

If it passes the pilots with flying colours, the basin could get a new lease of life.

Recommended for you