The North Sea oil industry has been in transition for some years following the collapse of oil prices in late 2014. Large cost reductions have been painfully achieved. Production has increased due to a combination of new fields coming on stream plus a substantial increase in production efficiency to around 75%. But new field investment expenditure has fallen dramatically since 2015 and exploration remains at a relatively low level reflecting principally the maturity of the province as well as oil and gas prices far below their pre-2015 levels.

Recent structural changes within the industry have highlighted the announcements of several large companies such as ConocoPhillips, Chevron, and Marathon to sell mature North Sea assets principally to new players often financed by private equity. To an increasing extent production and field investment depend on these new players. The availability of the Transfer of Tax History facility gives encouragement to the entry of new players to take over mature assets and hopefully extend the economic lives of the fields in question.

Collaboration, both among operators and between operators and the supply chain, has been advocated ever since the Wood Review. While progress has clearly been made within each of these categories there is also evidence that the extent of collaboration has stalled. It is important that the year 2020 produces enhanced cooperation in both categories. There is ample evidence that collaboration among licensees to develop fields in clusters rather than on a stand-alone basis, while difficult to achieve in practice, can produce reduced investment and operating costs to such an extent that more new fields become economic. Similarly, collaborative agreements between operators and supply chain contractors, if skilfully designed, can produce benefits to both parties. Increased recognition of these benefits with the active encouragement of the regulator could result in enhanced activity in 2020.

Transition should also continue with respect to the industry response to the climate change debate and the commitments of both the UK and Scottish Governments to Net Zero Emission targets. Currently, many studies are being undertaken to develop technologies which can reduce CO2 emissions in offshore production activities.

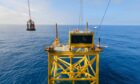

These include the employment of offshore windfarms to produce power for oil/gas installations which otherwise would have used diesel or gas as primary sources. Large batteries placed on the seabed beside the oil/gas installations could provide back-up power when the wind was not blowing. An alternative would be the provision of electrical power directly from the mainland to the oil/gas installations.

Studies are also under way on the possibility of generating electricity at offshore gas fields and then transmitting the electricity to offshore windfarms and subsequently to shore where it would enter the national grid. With the current low gas prices in due course “gas to wire” could become a viable alternative.

Carbon capture and storage has been studied in the UK for more than a decade without tangible results. The commitment to Net Zero Emissions should give an impetus to this technology, though clear Government support will be needed to ensure that initial projects proceed.

More generally there is a need for a clear Energy Policy statement by the UK and Scottish Governments indicating how the Net Zero targets can be met. There is increasing recognition internationally that a carbon price should be one of the instruments employed to encourage the development and use of less polluting technologies. In the case of the UK this could be via a continuation of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) or some variant of it when the UK leaves the EU. To be successful less allowances would need to be issued including a higher proportion via auctions.

The year 2020 should see transitional progress in the above categories. But activity in the UKCS will depend on how oil and gas prices develop. A new paper by the present author and Linda Stephen indicates that with a $50 price investment and production activity fall away sharply. At a $60 price investment and production enters a more gentle decline, while at $70 price investment and production increase significantly over the next few years.

Recommended for you