EnQuest’s decision to cease production from its linked Alma-Galia oilfields effectively brings to a close a 50-year chapter in the annals of the UK North Sea.

It was in 1971 that an obscure North American exploration company, Hamilton Brothers, discovered the Argyll field 190 miles south-east of Aberdeen.

In June 1975, Fred and Ferris Hamilton achieved the first ever commercial oil production offshore UK with Argyll, pipping BP’s Forties field.

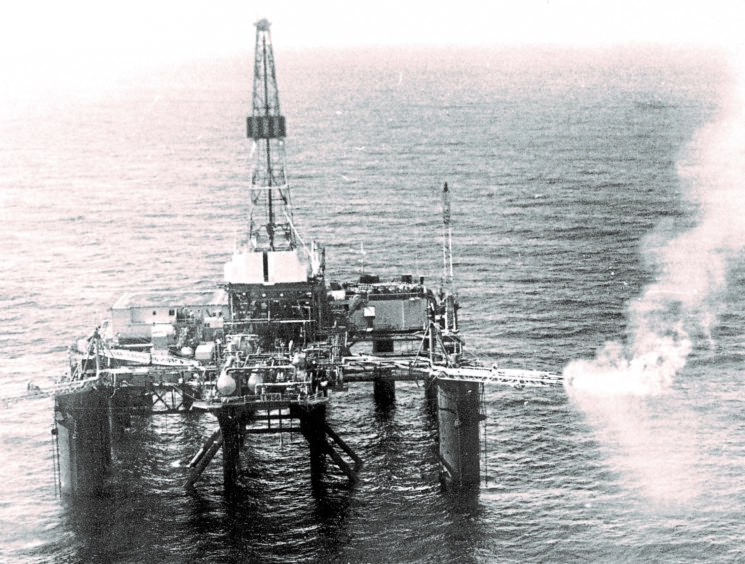

It was a remarkable feat. The brothers had taken the risk of converting the Transworld 58 semi-submersible drilling rig and tying it back to subsea wells.

This had never been tried before but it worked. The capital cost? A mere $73million (about $400m today).

Apparently, BP could have brought Forties on stream in 1974, but for the lack of an adequate contracting sector.

But if BP lacked experience, then so did the Hamiltons, though they had made their name onshore in Western Canada and Texas.

Reminiscing to the New York Times in 1975, Fred Hamilton said they had “set up shop” in Dallas in the late 1940s, borrowed $5,000 from their mother, bought a used rig on credit and began drilling contract wells for other companies.

Within 18 months, they were able to pay the $65,000 rig cost.

They did so well that in 1950 the Hamiltons founded their own oil company, with Ferris running the rigs and Fred working the deals.

Moving to Midland, Texas, they made their first big gas strike in 1956. After working out of Texas, and later Alberta, they set up their HQ in Denver around 1961.

In 1964 the decision was taken to try their luck in the North Sea, applying for and securing the UK First Offshore Licensing Round acreage that in turn delivered the Argyll field and its satellite.

In 1992, with output down to 5,000 barrels of oil per day, the decision was made to cease production from Argyll, decommission and relinquish the licence.

Despite the immaturity of the UK North Sea at the time, the question was already being asked whether it might be possible to restore production to abandoned fields.

Among the aspirants was entrepreneurial Dave Workman, who had been making his mark in offshore contracting.

In 2000, he launched a company specifically to pursue such possibilities and, in January 2002, Tuscan Energy together with another new-born junior, Acorn Oil & Gas, were awarded the licence to redevelop Argyll, which was renamed Ardmore.

A field development plan was granted in October 2002. The first Ardmore well was drilled in the summer of 2003 and “second” oil flowed in September 2003.

Ardmore is geologically complex with four distinct reservoirs.

Tuscan and Acorn decided on a plan that would involve drilling up to four high-angle production wells to recover 20-25m barrels over a two-year period with first production scheduled for late 2003.

Development drilling was carried out using the jack-up drilling rig, the Rowan Gorilla VII, which also served as the production facility for the field. But after a good on-schedule start-up, output quickly deteriorated.

In September 2003, the first completed well flowed at 20,000 barrels of oil per day.

However, after two months of sustained high rate, the well cut water. With a second well on stream, production peaked at 28,000 bpd of oil for just one day before the facilities, designed for 50,000 barrels of fluids per day, tripped-out.

All was not well. Facilities and well issues limited production. Worse still, Tuscan ran out of money, going bust and, in June 2005, Ardmore was shut-in at which point production was down to 6,000 bpd. It was left to Acorn to decommission the field. That task was completed in 2007.

Might Ardmore have worked if money hadn’t been so tight and more was invested in the wells and production facilities?

Perhaps. Just four years after abandonment, EnQuest decided the acreage was worth picking up and so, in 2011, Alma-Galia was born.

Alma was Argyll and Galia started out as Duncan. Their revised in-place reserves were revised to more than 300milion barrels and the recovery rate of the 37degAPI light crude was just 30%.

The prize was to be in the range of 20-30m barrels over up to 10 years.

The plan was to have six production wells and two water injection wells centred on two subsea templates tied back to the redeployed FPSO Uisge Gorm, renamed EnQuest

Producer. In fact, the fields host a total of eight production wells and one water injection well.

Alma-Galia began production in 2015 amid optimism that the more comprehensive (and expensive) redevelopment really would work. But it hasn’t and EnQuest is chucking in the towel. Production will likely cease during Q2 and the FPSO removed in Q3.

I await the final oil produced figure. Given the many issues that have dogged this project, it will likely fall well short of EnQuest’s dream.

I simply cannot see anyone returning for a fourth throw of the Argyll dice. It’s clearly too big a gamble.

Recommended for you