A senior diving boss has described how his son has been “crippled by incompetence” while preparing an oil rig for work in the North Sea.

Lewis Beddows, 24, has been left medically unfit for work after an air diving incident in Las Palmas in December 2018, working on the Ocean GreatWhite rig ahead of a UK drilling campaign.

An incident report seen by Energy Voice states “confusion” and a “breakdown in communication” on site led to a critical six-hour delay in Lewis receiving treatment for his injury – type two vestibular bends, a build-up of inert gas which affects the brain and nervous system.

His father, Derek Beddows, recently stood down from his job as the global diving technical authority for energy giant BP, based in Aberdeen, in order to support his son who lives in Norfolk.

Beddows Sr, who has worked in the industry since 1976 and lived in Westhill since 1995, likened the case to a “Shakespearean tragedy” and a “nightmare”.

He has called for lessons to be learned industry-wide following the incident, when the diving supervisor in charge decided not to put Lewis in a recompression chamber, which was the only effective treatment for the injury, according to the report.

After a year-long standoff with the contracting company Otech, the firm has in the last week got in touch via lawyers to “reach an amicable agreement” with the Beddows, but would accept “no formal admission of liability” and “will not do any interim payment”.

The Norwegian firm has not responded to repeated requests from Energy Voice for comment.

The diving incident report is signed by Otech’s chief executive and chairman, Odd Are Tveit.

Lewis, who began professional diver training at 16 and has worked around the world, including the North Sea, has been forced to sell his assets to “survive”, including savings to buy his first home.

MRI scans have shown that the 24-year-old now has 14 visible lesions on his brain and central nervous system, caused by the micro bubbles of nitrogen in his blood stream.

Dr Maarten van Kets, a specialist diving physician, said in a medical assessment that Lewis is suffering from “significant and ongoing” problems, with the delay in treatment “increasing the likelihood of incomplete recovery”.

These include reduced vision in his right eye, numbness and reduced sensation down his right side and difficulty with balance.

Beddows Jr had also been deemed to have suicidal ideation following the incident, which has altered his mental state, ability to concentrate and communicate, as well as his memory.

He is still in control of his faculties after a series of recompression treatments in the days and weeks following the incident, but his father said “he could have been killed or permanently paralysed”.

Dr van Kets’ assessment added that he would never expect the 24-year-old to be fit to dive again and he may “never regain a medical capability compatible with any gainful employment in the long run”.

Beddows Sr said: “In 44 years in the diving business, I’ve seen a lot of bends. I’ve been in the chamber with a lot of guys with bends but I have never seen a type two as bad as the one that manifested itself in my son, which makes this whole thing quite Shakespearean in its tragedy.

“I cannot believe, in this day and age, that this kind of thing still happens to a young man just doing his job.

“You spend your entire working life keeping divers safe and improving the lot of the diver in the water, the working man in the water, and BP are very good at supporting me to do that, and then your own son is crippled by incompetence.”

Beddows Jr contracted the decompression sickness after a series of dives on December 5,6,8 and twice on the 9th, in a schedule deemed “too aggressive” by the incident report.

He was carrying out welding work on the Ocean GreatWhite, the largest semisubmersible in the world, in preparation for its arrival at Kishorn Loch in the north of Scotland the following month.

Beddows Jr said the work was running behind schedule, leading to the additional dive – rig operator Diamond Offshore said it “would not be appropriate to comment” on a dispute between an individual and a third party company which it is not involved in.

A combination of factors, including “shortcomings” in planning for the work and a “lack of adequate response” to the incident led to Beddows Jr’s injuries, according to the report.

Signs of his illness showed up less than 10 minutes after the final dive, which Lewis describes as “being hit round the head with a bat”, losing hearing in the right ear and collapsing.

At that stage the diving supervisor decided not to use the “fully operational” on-site decompression chamber, which would have solved the problem, as he thought it was “faulty”, despite protests from fellow workers.

A witness statement describes how several diver medical technicians were “trying desperately to overcome the strong resistance to put him in the chamber but it did not happen” and an ambulance was called.

At no point was the Otech diving doctor notified that an incident was ongoing, meaning “decisions related to the treatment of the diver were consequently made without any input from accepted hyperbaric medical specialists”.

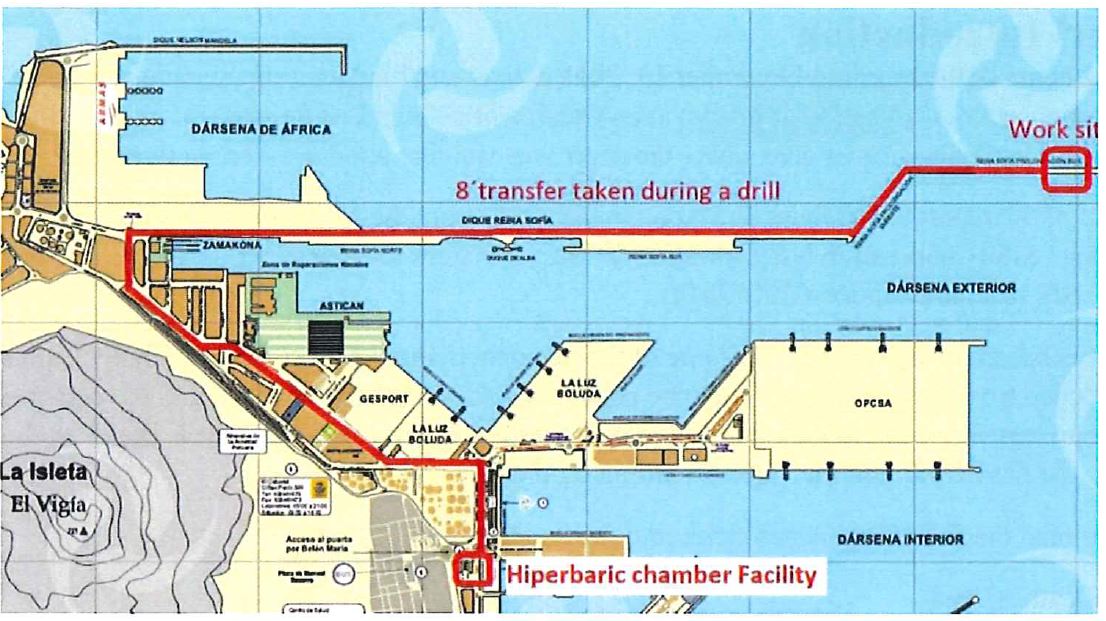

After the decision was taken not the use the chamber, Lewis was transported to a hyperbaric centre in Las Palmas for treatment which Otech had on contract for 24-hour emergency treatment, which turned out to be closed.

It was a full six hours after the dive, when Lewis had been flown to the neighbouring island of Tenerife, that he was finally recompressed.

The consequences of that delay are still keenly felt.

Beddows Jr said: “I’m not trained on anything else and I don’t know anything else. I don’t have the physical health, I don’t have the movement, the strength, the fitness or the knowledge to carry out any other work.

“I left school, I did the diving mechanical technician’s apprenticeship along with the diving courses and that’s all I’ve ever done, it’s all I’ve ever known.”

His father added: “He’s not the same boy now, he’s a different boy. He used to be quick, sharp, fast and thoughtful.

“I have to speak for him and I have had to attend a lot of the medical assessments with him, which has been pretty tough.

“Lewis, to a large respect, was my legacy.

“He hasn’t been able to work since Las Palmas in December 2018. He can’t go offshore, he’s lost his offshore and diving medicals and all the other industry training courses have now elapsed.

“I’ve got a 24-year-old son who no longer has a career anymore.

“He can’t dive. All he ever wanted to do was be a commercial diver and then be a supervisor, saturation diver and have a very good living in an industry that he loved being part of.”

Lewis previously dived for Otech in Norway in 2016, describing the standards then as “immaculate” and believes the same principles were not adhered to in Las Palmas.

Otech chief executive Odd Are Tveit is the Norwegian Consul to Las Palmas, and after a phone call to Lewis in January 2019 has since “refused” to communicate with the Beddows until his lawyers’ email last week.

Beddow Sr said: “They are playing a game of delay, divert and distract. They carry on working both in Norway and Las Palmas as if nothing has happened. He carries on being the Consul to Gran Canaria and enjoying that part of his life.

“In the meantime Lewis hasn’t worked for a year, he’s sold pretty much all his assets. Lived on his savings that he put aside for his first house.

“You cannot document the ripple effects of having your life and your career changed overnight.”

The diving incident report has made a series of recommendations to Otech, including carrying out risk reviews and taking into account the competence of diving supervisors in hyperbaric treatment.

Beddows Sr said a “failure” of the industry has been its inability to police companies like Otech and “measure the competence” of supervisors who are in control of divers’ lives.

Otech has been a member of the International Marine Contractors Association (IMCA) since 2017, which the trade body said came following “a successful audit with a good reputation and recommendation” but added that “clearly something seriously went wrong on this project”.

The group said its supervisor training scheme is “rigorous” and “far from easy as many candidates fail to make the grade”.

However, it conceded that improved tech and training means there are “far fewer decompression incidents” than in the early says of the industry, meaning “supervisors have much less experience of such situations”.

IMCA diving manager Brian McGlinchy said he was “deeply saddened to hear of the tragic incident” having long worked with Beddows Sr, but added that IMCA is not an enforcement agency and does not have legal powers to investigate, which in this case lies with Spanish authorities.

Another major lesson from the incident, specifically applying to the UK, is the need for “a more considered approach” to the risks around decompression.

Diver safety is covered by the Diving at Work Regulations 1997, with a specific set of Approved Codes of Practice for inshore diving, covering the likes of ports, harbours and jetties.

The regulations, revised in 2014, require an on-site decompression chamber if “significant risk” of decompression illness is identified for inshore dives of 10 to 50 metres, otherwise it can be “no more than six hours travelling distance” from the site.

The same applies for dives of 10metres or shallower, despite there being recorded risk of fatal embolisms, a bubble trapped in a blood vessel which can cause a stroke or heart attack, in some cases.

These apply where in-water decompression “stops”, a period to slowly rid gases like nitrogen from the diver’s blood stream, last no more than 20 minutes.

Beddows Sr added: “There needs to be a more considered approach that assesses the highest decompression risk.

“By way of example, a diver may suffer an embolism in 10metres of water, the only method of potentially saving his life is through immediate recompression.

“This requires a decompression chamber at the worksite.”

HSE stated that the regulations for any decompression stops lasting longer than 20 minutes do require an on-site chamber for immediate use.