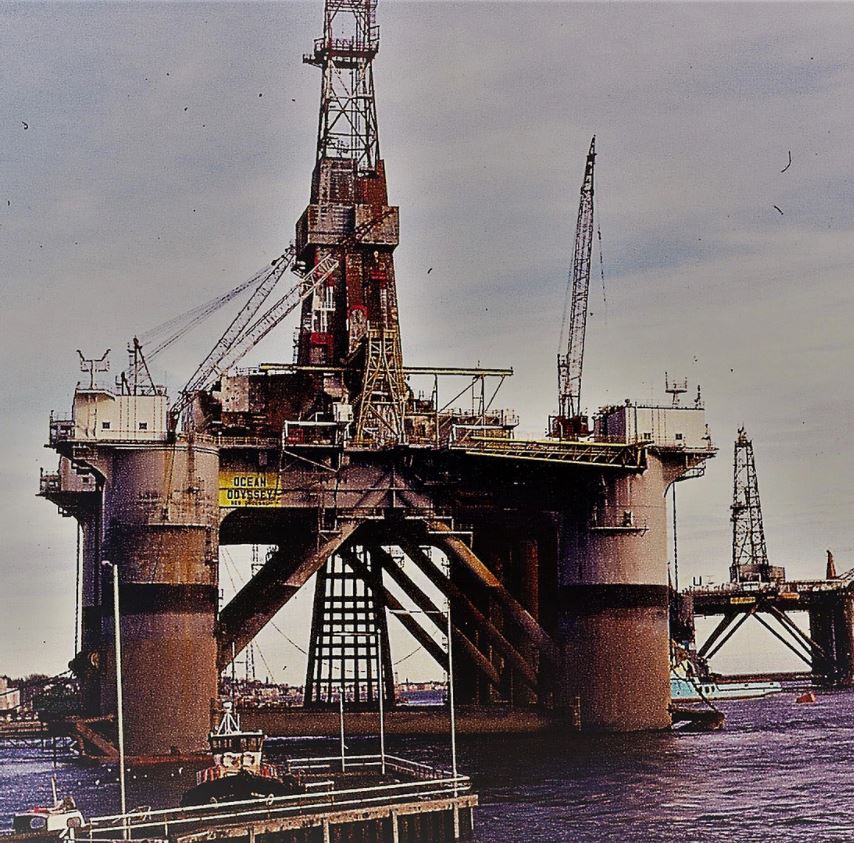

The blowout on the Ocean Odyssey exploration rig in 1988 is often overshadowed by Piper Alpha but is a significant event in oil & gas history.Derek Beddows, Archer Knight’s Director of Diving and Safety Services, recalls his time as part of the response, and the pioneering work which went into capping the well, 32 years ago this week.

It’s 32 years since the blowout on the semi-submersible exploration rig Ocean Odyssey. Owned by Odeco, it was drilling in the high-pressure/high-temperature central Graben area of the North Sea, for Atlantic Richfield (ARCO) and two other operators.

The explosion was caused by a sharp rise in casing pressure, which led to a gas kick. There was one single fatality; Timothy Williams, a radio operator, overcome from the effects of the heat and smoke, after he was ordered back to the radio room from the lifeboat.

Just 10 weeks before, 167 men had died at Piper Alpha, the worst offshore disaster in history and this often overshadows the Ocean Odyssey incident. As a result, it’s likely that important lessons which could have been learned from the incident, weren’t.

“…I was mobilised at once to the company’s emergency response centre in Aberdeen. From there, I flew out straight away to the MSV Sta-dive, which was already at the site of the explosion…”

At the time of the incident, I was working for ARCO in its Great Yarmouth offices on routine diving technical support. I was mobilised at once to the company’s emergency response centre in Aberdeen. From there, I flew out straight away to the MSV Sta-dive, which was already at the site of the explosion.

It was a tough environment to be working in. The Odyssey had just been removed, but there was debris in the water and the well was still venting hydrocarbon gases and fluids from the lower choke line. These were extremely hazardous conditions for diving operations.

The general ‘kill plan’ required the Sta-dive divers to install and operate various made-up valve assemblies; recover the lower marine-riser package; and remove the 5-inch drill-string assemblies that were still draped over the wellhead blowout preventer (BOP) – a specialised valve, used to seal, control and monitor oil and gas wells.

“…there was debris in the water and the well was still venting hydrocarbon gases and fluids from the lower choke line. These were extremely hazardous conditions for diving operations…”

To make matters more complicated, the BOP was also bent over by 14 degrees from the vertical, the end of the drill string was more than 350 feet from the wellhead on the seabed.

About 1,000 feet away from the wellhead was the semi-submersible rig Henry Goodrich. This was set up to support the well-kill activities, once Sta-dive had installed a line between the two locations and the Henry Goodrich had managed to get control of the well.

“The teams took a pioneering approach and there were many ‘firsts’ along the way”

I transferred to the Stena Seawell for the final abandonment works once the well was under control (again as the ARCO Diving Representative). I was stunned by how technically advanced the very new Seawell was, compared with other diving support vessels I’d worked on since the 1970s. Years later I’d be onboard her again for other North Sea and Irish Sea projects, with the Stena-Coflexip-Technip organisations. It was built to last and is still going today.

It’s impossible to overstate the significant input from the Sta-dive and Seawell diving team, engineers, ROV lads, and marine operations, particularly from ‘Seaforth Maritime’. They were all crucial to the successful well kill and abandonment operation.

“World’s first subsea perforation from a Monohull Vessel. FSV Stena Sea-Well. 24th October 1988. Block 22/30-b3.”

From start to finish, the response took a pioneering approach. As a result, there were many ‘firsts’ along the way that ultimately made the well kill and abandonment works a success.

One of the most significant ‘firsts’ was the industry’s first subsea perforating job from a monohull vessel, performed by the Seawell. An operation that seems more commonplace now. (I still have a photograph of a diver commemorating the moment, along with a U-Matic Tape compilation of all the subsea activities, given to me by David Sheppard of the Sta-dive team, I lent this to the Petans Survival Centre at Norwich Airport. It is a grim reminder of what happens when it does go wrong.)

During my career, I’ve been fortunate enough to have been involved in many memorable, and significant, projects in the North Sea and across the world.

Looking back, the on-site pioneering approach on a day-to-day basis, the achievements of several industry firsts, and the ultimate success of the operation, mean the Ocean Odyssey response is up there at the top of the list.

This article first appeared on the Archer Knight website.