A pair of offshore engineering specialists have revealed ambitious plans for a £10 billion floating wind project aimed at slashing emissions from UK oil and gas platforms.

But entrepreneurs Dan Jackson and Mark Dixon, of Cerulean Winds, say they need “urgent” action from government if they are to help oil firms tackle the single biggest challenge in their histories — decarbonisation.

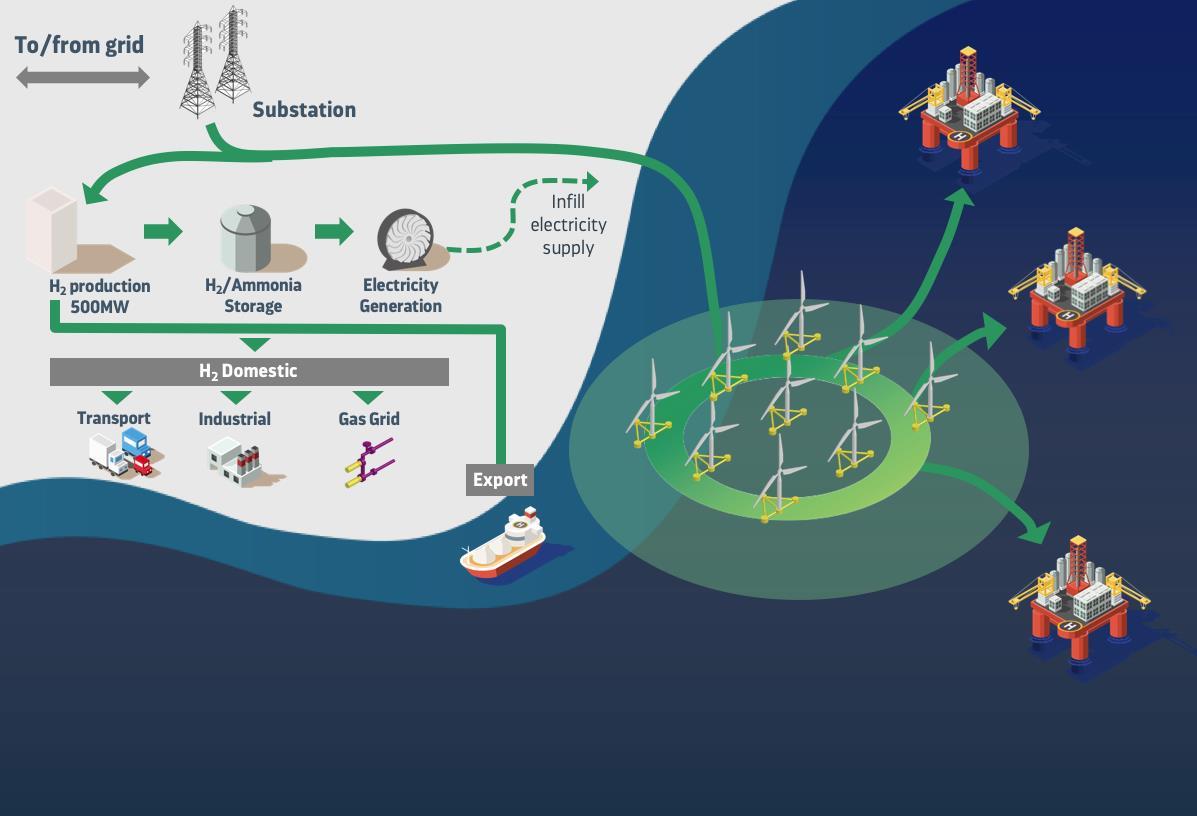

They want to install 200 of the largest floating turbines across two sites west of Shetland and in the central North Sea, with the electricity used to power oil and gas platforms.

Cerulean claims the wind farms would cover power demand for “the majority” UKCS platforms, which stands at about 24 TWh/year, according to a recent report from OGTC.

The plans may sound optimistic, but the two men say they have lined up “household-name” contractors to deliver the project and convinced major financial services houses that the venture would turn a profit.

They also have a strong track record of leading large-scale offshore infrastructure developments over the past 25 years.

They had a hand in Chevron’s US Gulf of Mexico Jack and St. Malo project, which is relevant to Cerulean’s plans due to its use of high-voltage cables to power subsea equipment.

In 2000, the duo set up consultancy DeepSea Engineering, which was acquired by McDermott International 13 years later.

And they headed up io oil and gas consulting, a joint venture between McDermott and Baker Hughes, launched in 2015.

Since founding aspiring green energy company Cerulean in London a year ago, they have focused on infrastructure planning, firming up the business case and speaking to potential backers.

Cerulean is being advised by financial services group Societe Generale and investment bank Piper Sandler, whose project finance managing director, Tim Hoover, says the scheme “understands the needs and requirements of the financial markets to make it bankable.”

At £10bn, the sticker price is eye-watering, but Mr Dixon has tested the market for financing — through debt and equity — and is confident there is “appetite”.

He said institutions with deep pockets are “waiting for the starting gun to fire”, which depends on Cerulean passing the regulatory approval stage.

Mr Dixon said the areas Cerulean wanted to develop were in close proximity to oil platforms, but were not included in the ongoing ScotWind leasing round, managed by Crown Estate Scotland.

Zoe Crutchfield, head of Marine Scotland’s licensing team, said at an event last month that work was under way to assess whether a specific leasing round for wind projects to power offshore oil installations would be viable.

Mr Dixon said that process would take too long and is calling for Cerulean’s scheme to be granted leases and fast-tracked.

Mr Jackson said the consequences of not moving quickly enough would be “catastrophic” for employment and the economy.

He said: “The decision to proceed with the scheme will ultimately rest with the Scottish Government and Marine Scotland and their enthusiasm for a streamlined regulatory approach.

“The ask is simply that an exceptional decision is made for an extraordinary outcome.

“We are ready to deliver a self-sustained development that will decarbonise the UKCS and be the single biggest emissions abatement project to date.”

A spokeswoman for the Scottish Government said any decisions taken would be “communicated in due course through the proper channels”.

The UK oil industry is under pressure to shrink its carbon footprint, and platform electrification has been identified as one of the best ways to do that.

Last month, Neivan Boroujerdi, principal analyst, Europe upstream, at energy research firm Wood Mackenzie, said the west of Shetland and central North Sea basins would have to be completely electrified to achieve government and industry’s green goals.

But retrofitting existing platforms would be very expensive and the process is “as complicated as open heart surgery,” according to Steve Phimister, Shell’s former North Sea boss.

WoodMac said in a recent study that connecting platforms to onshore power sources was “a challenge”, as subsea cabling costs £1-2m per kilometre and many platforms are more than 200km from shore.

Mr Dixon said putting wind turbines closer to platforms would help take the sting out of those costs.

He also said Cerulean wouldn’t require subsidies through the government’s contracts for difference scheme.

Cerulean is targeting financial close in the first quarter of 2022, with first power on the slate for 2024.

The company would build up to the full complement of 200 turbines over the following two years.

Mr Dixon said Cerulean hoped to establish an operational base at Sullom Voe Terminal in Shetland, which would create hundreds of jobs.

If they get the all clear, the wind farm west of Shetland would be called Aspen and its central North Sea sister would be named Beech.

Excess power would be directed to onshore green hydrogen plants.

Gunther Newcombe, who is leading the Orion project, which seeks to build out offshore wind, hydrogen and platform electrification around Shetland, said: “The Orion team has been working closely with Cerulean Winds to explore offshore electrification and hydrogen options in the Shetland region, and we welcome today’s announcement.

“We are aligned with Cerulean Winds’ overarching goal to use offshore wind energy to electrify offshore oil and gas assets to deliver net zero and develop green hydrogen on Shetland as part of the energy transition agenda and create employment on Shetland and the wider region.

“Shetland is perfectly placed both geographically and from a skills and assets perspective to lead the charge in green hydrogen production from offshore wind.

“Cerulean Winds’ progress is a major step in the right direction for a bright, sustainable future for Shetland and the broader UK energy industry.”

Recommended for you