A “tough challenge” awaits if the UK is to replicate Norway’s successes in decarbonising offshore assets, Wood Mackenzie has forecast.

According to analysis from the energy research organisation, there are four key barriers to platform electrification in the North Sea – carbon pricing, cost, capex and power source.

Decarbonising offshore assets will be fundamental if oil and gas companies are to retain their licence to operate in the years ahead.

Investors and regulators have put the onus on firms to bring down their operational emissions, in line with climate change targets.

About two-thirds of operating emissions coming from power consumption – production, processing and liquefaction – according to WoodMac.

Divesting heavy emitting assets is an option for companies, but it does nothing to reduce the world’s emissions – there is evidence it could actually increase them.

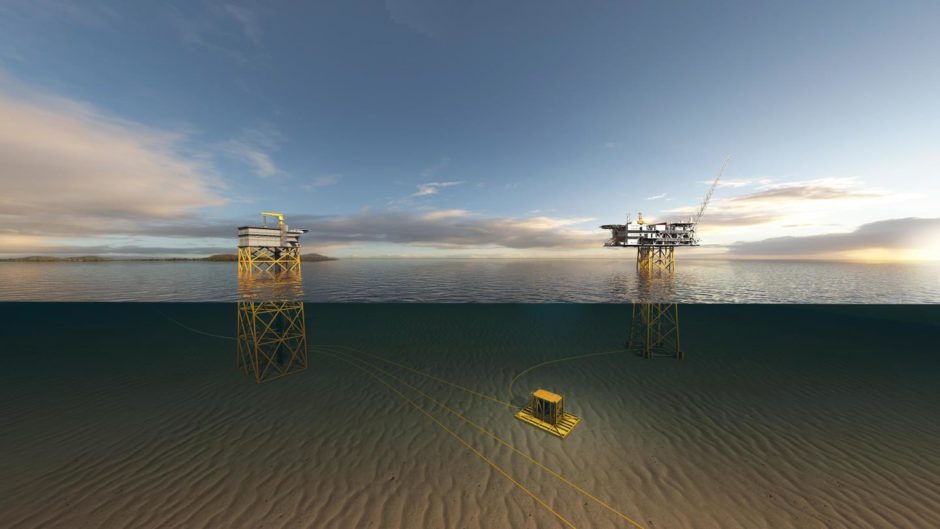

An alternative is to electrify platforms, something Norway has been doing for decades with “significant” success.

WoodMac said: “Norway embarked on this journey decades ago, and activity continues to ramp up.

“Nearly US$5 billion of platform electrification spend will be sanctioned in the next two years, according to Lens Upstream. (Those sanctioned by the end of 2022 will benefit from temporary tax terms that improve the economics.)

“Norway’s strategy is paying off. Electrification has helped to realise emissions savings of around 25% and kept absolute emissions flat, despite an increase in activity and infrastructure.”

A commitment to supply green electricity to offshore assets was included in the North Sea Transition Deal, an agreement between government and industry signed earlier this year.

Through the pact, £3 billion was earmarked for electrification of installations, while a target to reduce emissions from oil and gas production by 50% by 2030 was also set.

The question WoodMac poses though is “can the UK replicate Norway’s success”?

Electrifying assets is “not straightforward”, the organisation said, and the “economics are challenging”, particularly given field maturity in the UK.

Norwegian fields have typically had 20 years of remaining life before being electrified.

But in the UK, a minimum remaining field life of 10 years would rule out nearly 50% of fields, rising to 90% for those with 20 years.

TotalEnergies (LON: TTE), previously Total, recently told Energy Voice that it planned to prioritise decarbonising its assets with longer left to run, such as Elgin-Franklin and Culzean.

The French supermajor is also part of a study, alongside some of the North Sea’s biggest hitters, into platform electrification.

Given their lifespan, offshore hubs in the Central North Sea and West of Shetland are the “best candidates” for decarbonisation.

But “significant investment and rapid action” will be needed to meet North Sea Transition Deal targets, WoodMac said.

It added: “We see four key barriers to UK electrification. While carbon prices have increased following the recent gas supply crunch, they are still too low to incentivise electrification. Without cost reductions or funding support, an eye-watering carbon price of US$250/tonne would be required to cover the capital cost of a typical standalone electrification project.

“Costs need to come down. Collaboration, allowing multiple fields and partners to share infrastructure, is needed. Hub-led solutions have typically reduced costs by 50% on an emissions-saved basis and could bring the ‘carbon breakeven’ price down to US$125/tonne. State grants, similar to Norway’s NOx fund, would bring it down further.

“There is limited tax relief in the UK compared to Norway. Uplift on capital spend associated with decarbonisation (not just against supplementary charge payments) would encourage investment. Refunds on tax losses, similar to those for E&A spend in Norway, would incentivise companies not in a tax-paying position.

“The UK currently lacks the infrastructure to power offshore electrification. Grid access and regulation around pricing needs to be prioritised. Power from the Norwegian Grid is an option, but supply and regulatory concerns could result in push-back. Offshore wind is another candidate, and with costs coming down it could be an important part of the solution.”

© Supplied by Aker Solutions

© Supplied by Aker Solutions