How close are Scotland’s ferries to running off hydrogen? Peter Ranscombe sets sail to find out.

Standing on the deck of a ferry is an experience that fills the senses.

There’s the sight of the wake spreading out behind the ship, the sound of gulls crying overhead and the feel of the cold wind whipping around your cheeks.

Then there are the smells too, from the bracing salty air of the sea through to the tempting scent of the pie and chips wafting out from the galley.

There’s one smell that few passengers would miss though – the fumes from the exhaust for the diesel engines below deck.

Yet, perhaps within a generation, that particular smell could be consigned to the history books if Scotland’s ferries switch to running on hydrogen.

Diesel – along with other fossil fuels like petrol, coal, and natural gas – burn in the oxygen in the air to form carbon dioxide, one of the worst greenhouse gases that are causing climate change.

Hydrogen, on the other hand, combines with oxygen in the air to form water vapour, a harmless gas that will eventually condense back into liquid water.

Yet hydrogen does present challenges – if it’s stored as a gas, it takes up about seven times the space of the equivalent amount of diesel that would be required to produce the same amount of power.

There are alternatives though, including combining hydrogen with nitrogen to make ammonia – best known as a key ingredient in fertilisers.

While electric vehicles like cars and scooters can – in effect – be plugged into the mains to recharge their batteries, hydrogen is being investigated as a potential fuel for more power-hungry modes of transport, stretching from trucks and trains through to light aircraft and ferries.

European Marine Energy Centre at forefront

The European Marine Energy Centre (Emec) on Orkney has been at the heart of producing hydrogen and finding uses for it.

Having been involved in the early development of both wind turbines and tidal devices, Orkney produces more renewable energy than it can use.

To capture some of the spare renewable energy Emec connected tidal devices at its Eday test site to an electrolyser, a machine that uses electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen.

The original electrolyser hit problems in the salty environment, but a beefed-up version is being installed.

It s due to start operating in the new year, while the centre also has a portable electrolyser.

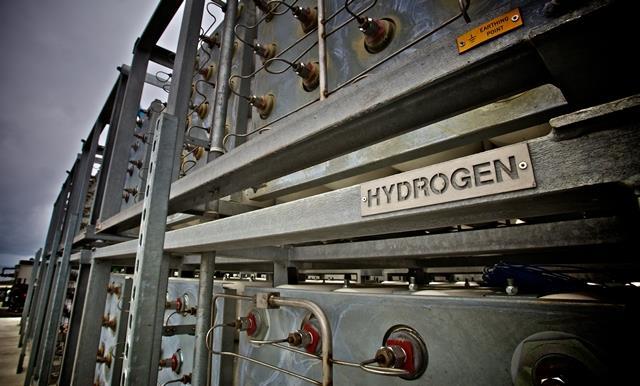

Hydrogen produced by the machine is stored on a trailer in cylinders wrapped in Kevlar, which has allowed Emec to transport the gas to locations where it’s needed for tests.

Those tests have included the “hydrogen diesel injection in a marine environment” (HyDIME) and “hydrogen in an integrated maritime energy transition” (HIMET) projects.

HyDIME aimed to burn hydrogen alongside diesel in an auxiliary engine on a ferry, reducing the amount of diesel needed.

“We’ve encountered some regulatory challenges with the Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA), which has meant we’ve got to the point where we can’t complete that project,” explained Neil Kermode, managing director at Emec.

He added: “Even though basically the same equipment is used in the automotive sector on land, the MCA is not happy yet for it to be used on a ferry.

“We’ve ended up stopping the HyDIME project for the moment, but it’s given rise to our second project, HIMET.”

As part of the HIMET project, Emec is putting hydrogen into an engine that’s similar to the one that would have been used on a ferry during HyDIME, but on a test rig in Shoreham on the south coast of England instead.

“That should allow us to answer a number of the questions the MCA threw at us about the other project,” Mr Kermode said.

As well as the demonstrations on the test rig, HIMET is also investigating how to use hydrogen in a fuel cell on a ferry.

Need for more speed

However, MCA regulatory requirements mean the fuel cell cannot be used to run any of the ship’s systems.

Mr Kermode is frustrated with the slow pace of regulatory change.

He added: “The fundamental problem is regulations written for shipping don’t specifically cover the sort of things we need to do now with hydrogen.

“There’s a genuine need to make sure the whole of government has recognised that, in an era when we need to decarbonise, we need to be pulling all the levers to work out how we can decarbonise as quickly as possible – and that will involve changes to regulations.”

Getting new equipment certified to meet regulations is also at the forefront of John Salton’s mind.

As the fleet manager and project director at Caledonian Maritime Assets (CMAL), which owns the ferries, ports, harbours, and other infrastructure used to run services on the west coast, the Firth of Clyde, and in the Northern Isles, Mr Salton is heavily involved in the “HYSEAS III” programme.

The Europe-wide scheme – which involves Orkney Islands Council, St Andrews University and several European partners, alongside CMAL – is designing the continent’s first sea-going ferry powered by hydrogen fuel cells.

It may in future run lifeline inter-island services between Kirkwall and the island of Shapinsay.

It is a long process; the equipment is currently being tested at Bergen, in Norway, while the designs are being assessed by DMV, a classification society involved in approving ships for use at sea.

By April 2022, Mr Salton expects to have a design and specification, and be ready to build a ferry once conversations about funding have taken place between the local council and government agency Transport Scotland.

The hydrogen-powered vessel could cost around £17 million at today’s prices, compared with around £9m for a similarly-sized, diesel-powered ferry.

“That’s an awful lot of money for a small ferry but it’s not cheap to be green,” Mr Salton added.

“And particularly when you’re first-of-class on an innovative new design and new fuelling system.”

Lessons learned in designing the ferry will also be applied to larger vessels that are likely to run on ammonia, rather than hydrogen.

In the meantime, larger ferries ordered by CMAL are likely to run on liquified natural gas instead of diesel, with the option to upgrade them to ammonia in the years ahead.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Emec

© Supplied by Emec © Supplied by Submitted pic (Credi

© Supplied by Submitted pic (Credi