There are several hubs around the North Sea which will still be producing in a decade’s time – but 12 of these will be “key” thanks to their production upsides and emissions intensity, according to new research.

Analytics firm Welligence has produced the data identifying the dozen production bases in the UK, from the West of Shetland to the Southern North Sea.

Emissions intensity in the UK currently sits at around 22 kg of CO2 equivalent per barrel of oil equivalent (boe) – around four-times higher than the CO2 output in Norway.

Increasing production is a key means of reducing that intensity, but that option will only be available to the hubs with sufficient upside nearby to exploit.

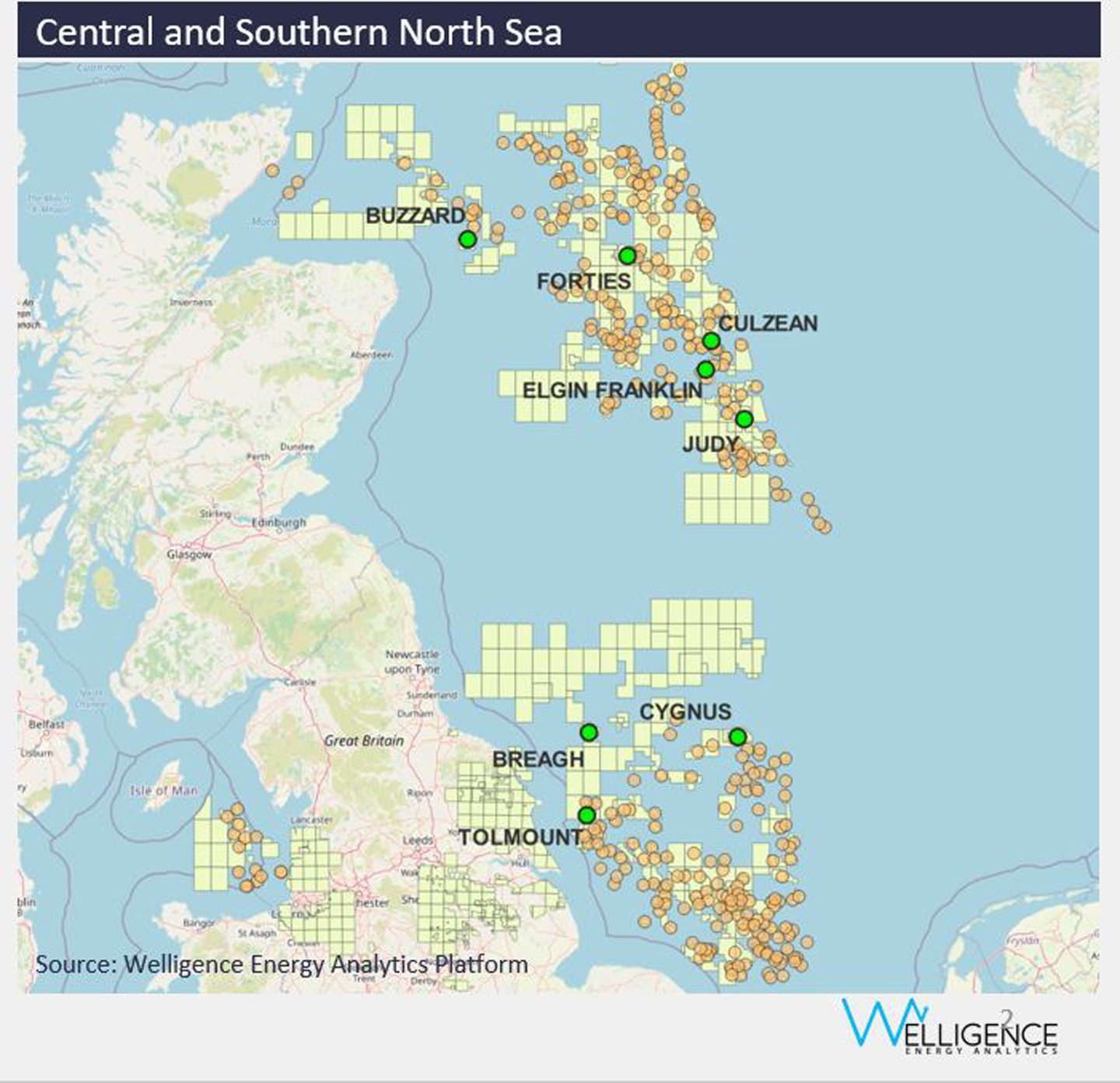

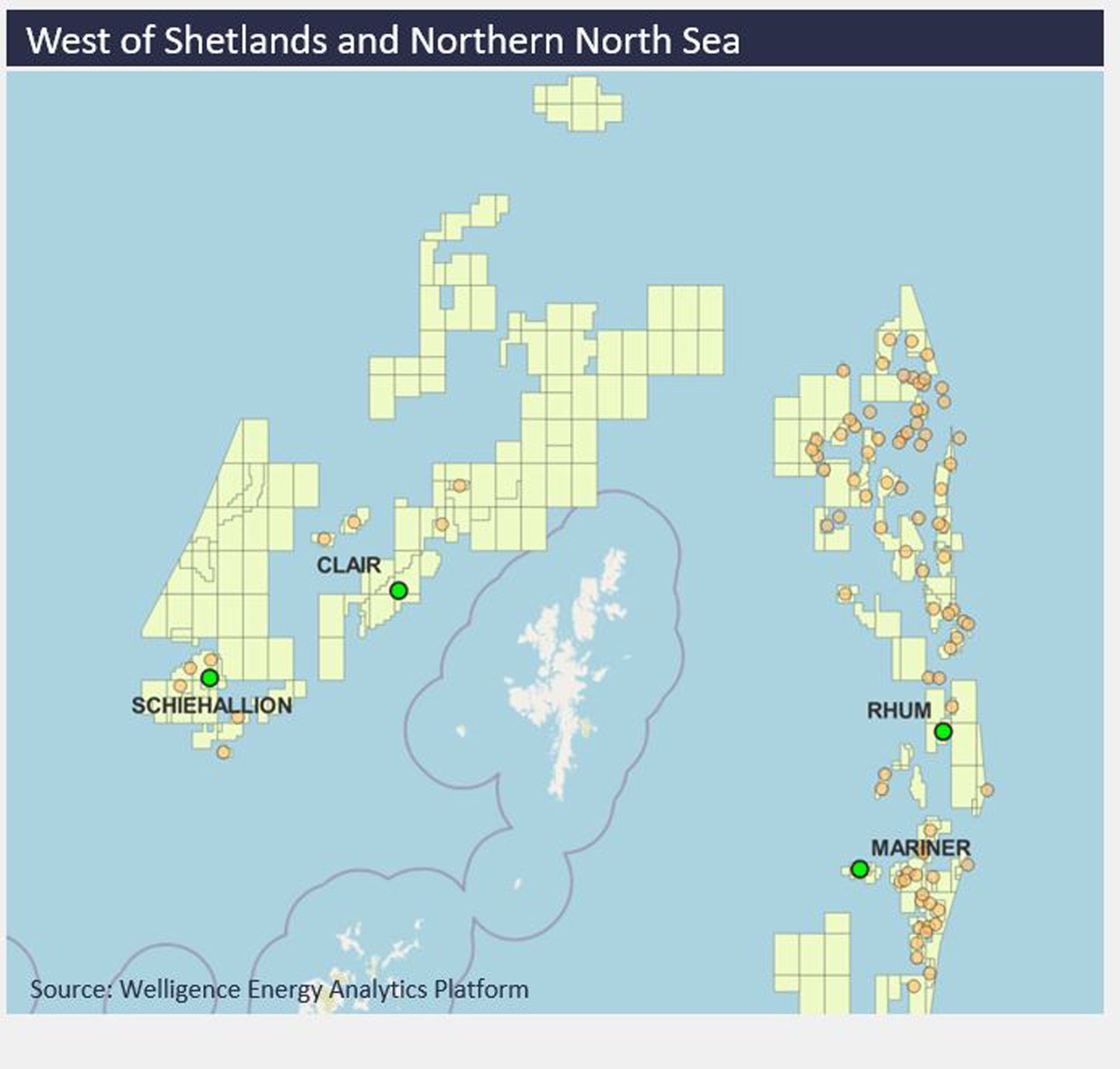

Clair and Schiehallion in the West of Shetland, Mariner in the Northern North Sea and Buzzard and Forties in the Central North Sea are among the 12 identified.

Vice president of North Sea research, Dave Moseley, presented the stats at the Devex conference in Aberdeen last week.

He said: “The title of the presentation was ‘What are the fields that are going to be here in 10 years’ time?’ This is us taking a view on that based on longevity of hubs, upside around certain fields and also assets that are attractive from an emissions perspective.

“In terms of future M&A processes, cleaner assets are certainly going to be more attractive to companies that have ESG targets.”

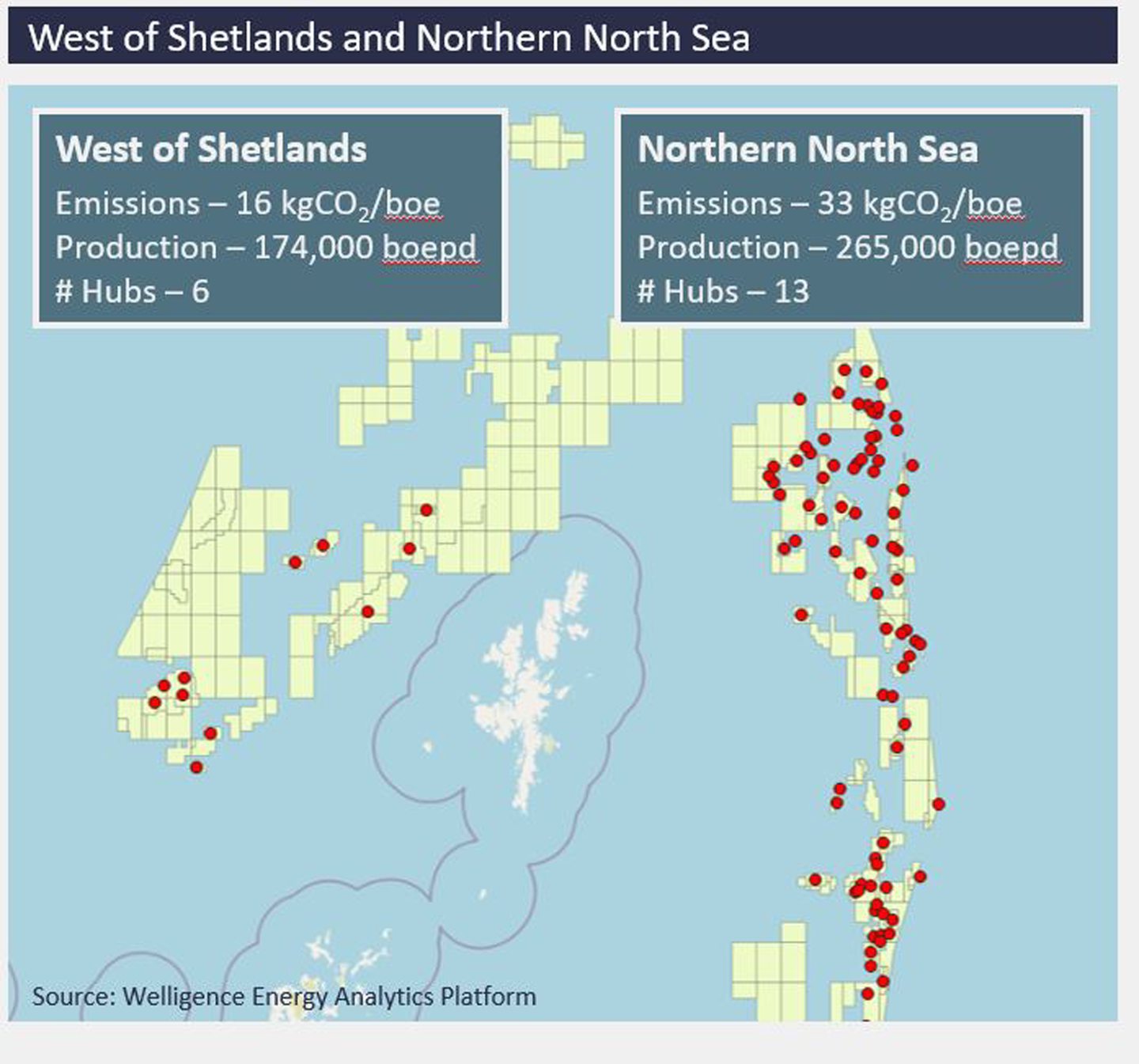

Alongside Clair and Schiehallion in the West of Shetland, Rosebank and Cambo could be added to the equation soon. They could further reduce the intensity of the region, currently at 16kg CO2e / boe, down to levels comparable to the Southern North Sea.

In the Northern North Sea, alongside Mariner, Rhum is a hub which has further potential, particularly if operator Serica Energy finds success with its upcoming Eigg exploration prospects.

The NNS currently has an emissions intensity of 33 kg CO2e/ boe across 13 hubs, many of which are older installations.

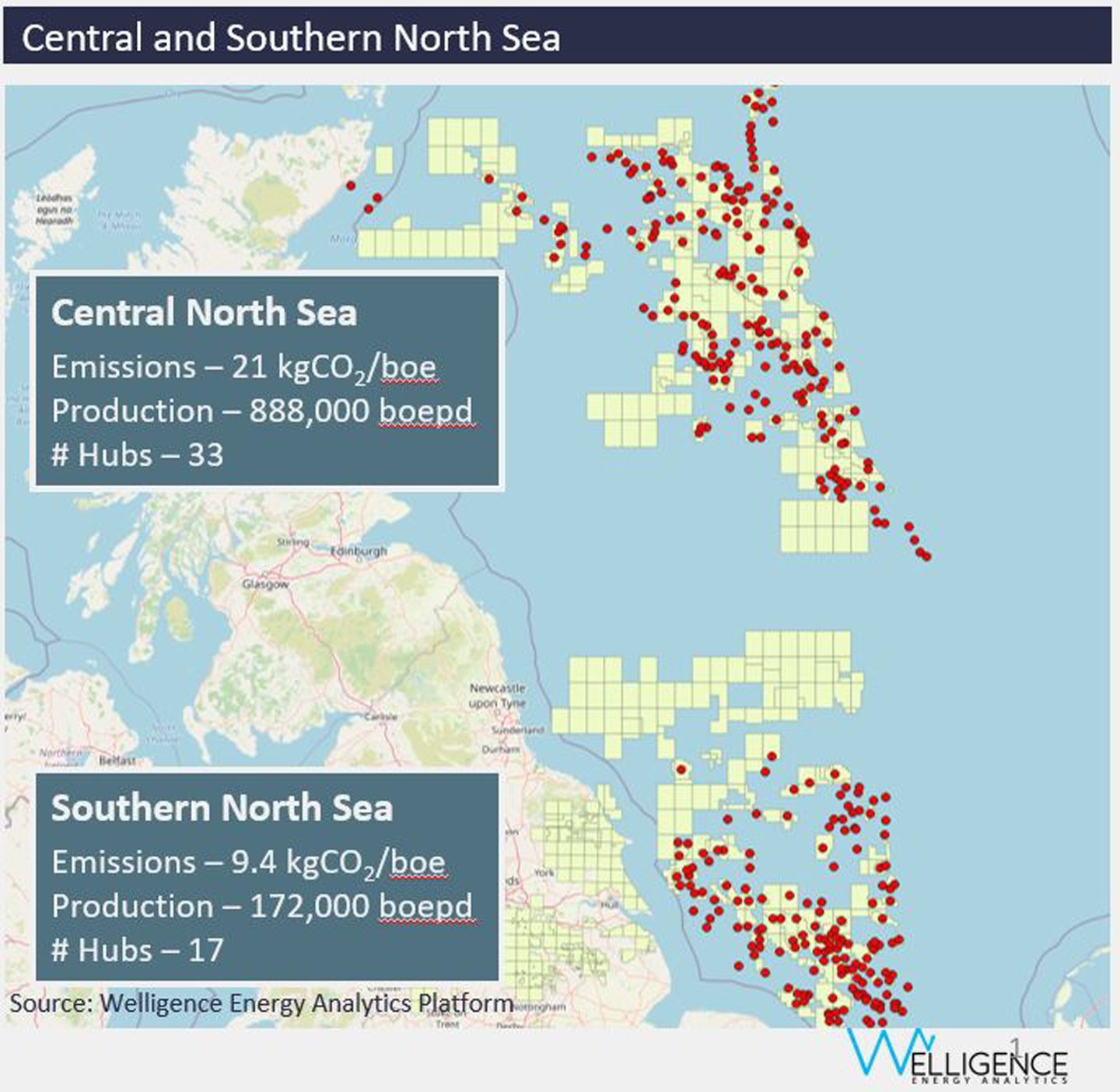

By comparison, the Central North Sea sits at 21kg CO2e/ boe, about the average for the whole UK sector.

It is expected to have hubs producing “for the next 15-20 years”, Mr Moseley said.

The Southern North Sea is seeing an activity resurgence with new hubs like Tolmount coming online and new exploration from firms including Shell and Deltic Energy.

Its emission profile at present is 9.4kg/ CO2e and is home to Cygnus, the lowest-intensity emitter in the UK at around 2 kg of CO2 per barrel.

Even Cygnus, though, plays second-fiddle to Norway where the best asset by far is Johan Sverdrup.

“For context, emissions from Johan Sverdrup equate to .25 of a kg of CO2e per boe,” Mr Moseley said.

“That’s the equivalent carbon footprint of half a latte.”

Buying power

Low emissions intensity is yet to take hold into M&A strategies in the UK, Mr Moseley said, though that’s about to change, and it differs from trends seen in Norway.

“Norway is a different basin and what we’re seeing there is M&A activity actually starting to be focused around some cleaner assets.

“To the point that, you could argue, some deals may even be having premiums paid for these lower-emitting assets.”

Welligence pointed in particular to AkerBP’s purchase of Lundin and, on a smaller scale, Pandion Energy’s purchase of ONE-Dyas’ Norwegian business as recent examples.

Dealing in absolutes

Following the presentation, an audience member argued that emissions intensity doesn’t help the industry’s “societal image” as firms “can increase production and say you’re improving your emissions intensity, whereas your actual emissions go up”.

Firms like ConocoPhillips have argued that their business of buying, swapping or selling oil and gas developments “could render an absolute target redundant” so an intensity goal allows it to carry out M&A activities without having to reset its overall target.

However groups like Australia’s Climate Council and Follow This have argued that absolute reductions are a “more concrete measure”.

Mr Moseley said Welligence used intensity targets here as it makes the most sense for looking at “not just trying to reduce emissions overall, but balancing that with domestic indigenous production”.

The picture on an absolute basis remains positive, however.

He added: “If you run three to four years into the future, we’re seeing quite a large number of hubs that are going offline and being decommissioned. Those are ultimately impacting absolute emissions.

“If you took the absolutes out to 2030 then there are big decreases in that. If you combine that with improvements on current facilities, reducing things like flaring, for instance, it is definitely a positive picture.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Welligence

© Supplied by Welligence © Supplied by Welligence

© Supplied by Welligence © Supplied by Welligence

© Supplied by Welligence © Supplied by Welligence

© Supplied by Welligence