Jake Molloy of RMT has been a part of the North Sea story for more than four decades; always on or directly involved with its shop floor.

Indeed there is probably no-one better qualified to run the rule over industry safety and the often uncomfortable road which it has travelled.

“When I started out in the oil & gas industry in 1980 there wasn’t even a survival course,” recalls Molloy.

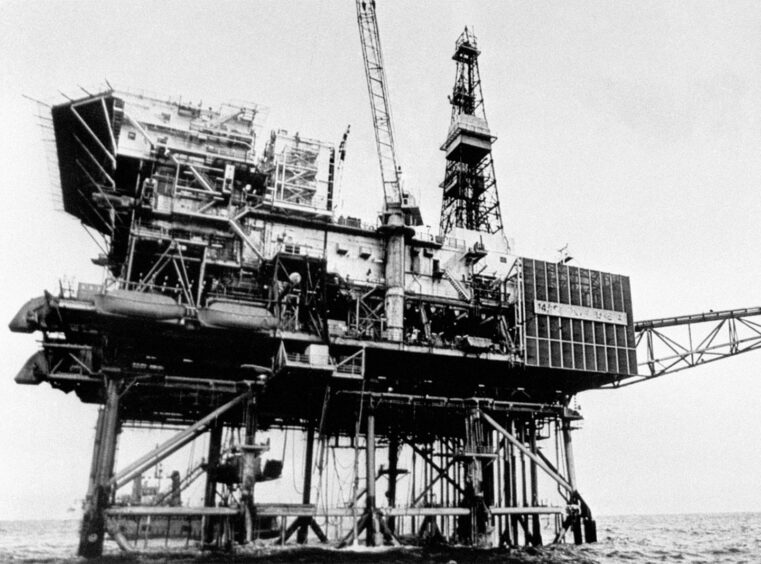

“It started with my first ever fixed wing flight and then a helicopter ride out to this monster of a platform, Ninian Central.

“I had no idea, absolutely no idea what I was letting myself in for, the environment that I would be working in or where it might lead me.

“I became aware of a variety of messy events along the years. Fortunately I didn’t see people killed but was conscious that some offshore workers died on the job; none more so than on July 6 1988 when Piper Alpha blew up killing 167.

“There weren’t any mobile phones; you had to log into the platform’s exchange to book a call and then it was for only three or four minutes before you were cut off. And those who ran the exchange invariably listened to your calls.

“Nothing was instantaneous and, in the case of Piper, it was a couple of days later when we finally got to see pictures of the disaster.

“It really drove home just how dangerous the place I was working on was. I was on Brent Delta (Shell Expro) working for a company called Lasalle.

“I had phoned home that night and had passed the radio-room. The radio operator said there was something going on aboard Piper; that up to six people were possibly dead.

“I thought: ‘Wow, it sounds like a big one.’

“Anyway. I spent five minutes on the call home then came back by the radio-room. ‘Any update?’ I asked. ‘No,’ said the operator. ‘But there’s an incident still going on.’

So Molloy headed for his bunk’ learning the following morning that Piper had blown up.

“There was silence in the tea-shack. Guys were trying to comprehend what had happened.

“Bit by bit they started talking about pals and colleagues they knew in the industry and who was working on Piper.

“I knew Bobby Ballantyne; he had gone to Piper and I was wondering if he was onboard. It turned out that he became one of the 61 survivors of that terrible night.”

It is the Piper disaster that triggered the Cullen Inquiry, which reported at the end of 1990.

Just before that, when the Offshore Installations (Safety Representatives and Safety Committees) Regulations were launched in 1989, Molloy decided to throw himself into becoming a safety rep whilst working as a helicopter landing officer in Shell’s Brent field for seven years.

Later, he was elected to the OILC (Offshore Industry Liaison Committee founded by Ronnie McDonald in July 1989) as general secretary.

That was January 1997, exactly the same year that Step Change in Safety was launched by the UK offshore industry in September and with which Molloy has had considerable engagement ever since, including serving as a director 2015-19.

Step Change in Safety

For the following 25 years, Step Chance has featured large in his work.

“It was launched with great ambition and I remember being somewhat dismissive at the time,” says Molloy.

“I didn’t believe that the systems needed to effect the kind of changes that the initiative was looking for were there to support the 50% reduction in incidents and accidents target during its first three years of operation.

“Ultimately (and unfortunately) we (OILC) were proven right.

“Indeed, in September 1999 we went to the press with a report about Shell, stating that it was failing to comply with more than 60 of Lord Cullen’s 106 Piper Inquiry recommendations.

“This was made all the more shocking by the fact that, even before the Inquiry got under way, North Sea operators were pouring billions of pounds into major improvement programmes as was well known that all were seriously wanting on the safely front.”

Arguably, the launch of Step Change itself was compromised by the fact that 1997 marked the slide into the second global oil price crisis and which hit the North Sea hard.

Operators became interested in just one thing, battening down the hatches and slashing expenditure to the bone; not that there was much muscle to trim following four years of intensive cost-cutting designed to ensure survival of the UK offshore oil & gas industry. Little wonder Molloy was sceptical.

All they could see at the OILC was a rash of prohibition notices issued by the Health and Safety Executive’s Cullen-recommended Offshore Safety Division regarding verification of safety critical standards.

To change the corporate culture at that time would require extensive workforce engagement and real empowerment through the safety rep system.

Molloy says his relationship with the various industry leaders trying to make a success out of Step Change was in fact good; just as, in 2003, the North Sea was embarking on what became the longest and most profitable period in its history.

“Look, everyone wanted the same thing and all main operators were keen to be seen to be involved, supportive and to be at least seen together in the same room in that context.

“OILC was at that time not an official trade union. We were seen as outsiders to the TUC.

“We were cynical as the UK Offshore Operators Association, which morphed into Oil & Gas UK in 2007, was running it.

“By and large it was mostly HSE personnel employed by the companies working on secondment that held Step Change together in the hope that they could make it work. They were trying to bring about change, as were we.”

The relationship between Step Change and OILC, later RMT, changed; notably there seemed to be a respect developing towards the trade union efforts to make the North Sea a safer place.

Things between the unions and the initiative began to improve, probably after 2003 when two workers, Sean McCue and Keith Moncrieff, died on board Shell’s Brent Bravo.

The pair had been sent into a utility leg for repair work, succumbing to inhalation of hydrocarbon vapour.

A Fatal Accident Inquiry later found that their deaths were “preventable” had Shell carried out appropriate repairs on a corroding pipeline.

“We started to share information; to look at issues collaboratively and to work behind the scenes,” Molloy recalls.

“The regulator (HSE’s Offshore Safety Division) became more involved too. There was a shift of attitude and, for example, they created the Workforce Involvement Group which they also chaired. The HSE invited safety reps on a regular basis to the big meetings.

“That led to a greater understanding of and engagement with the workforce. And Step Change had a key role in driving that.”

However, Molloy recalls that unhappy undercurrents became increasingly apparent from about 2010 onwards. Step Change was perceived by a growing number of workers as being in the pocket of the bosses.

But, to everyone’s credit, something was done about it.

From January 2015, Step Change became independent following “confusion over roles, functions and relationships”. It became wholly owned by its 137 member organisations and led by former Oil and Gas UK (OGUK) staffer Les Linklater.

He said at the time that Step Change had to “represent every part of the oil and gas industry”.

“We cannot do this without collaborating with operators, contractors, regulators and the unions,” said Linklater – and Molloy was invited to join the board!

Molloy was very clear that attitudes had to change. StepChange was never going to work properly unless the killing field of so much effort to make the North Sea a safer place – middle management – was dealt with.

Also, it could not just be top-down in its approach. It had to be bottom-up too.

Despite the best efforts of the HSE and the RMT, Molloy’s recollection is that the North Sea in reality had a “disengaged, disillusioned, disenfranchised, apathetic” workforce that simply did not believe the messages coming from the top.

Molloy warns: “And then suddenly there’s a bang, something serious happens offshore and people die. Then how does everyone cope?

“I think we’re in that environment now as the pressures on the oil & gas sector once again build.”

However, and Molloy is acutely aware of this, 25 years is a very long time during which to try and consistently drive forward an initiative like Step Change.

The departure of Linklater in March 2019 to “pursue a next step in his career” did not help, though his successor was found rapidly.

In May that year, Piper Alpha survivor Steve Rae was appointed to head the organisation and drive it forwards again; the fourth oil price crash, covid pandemic and growing climate change crisis notwithstanding.

Rae was no stranger to Step Change as his relationship dates back to 2007 when he became a member of its leadership team.

As far as Molloy is concerned, Rae is the right person to lead Step Change today and that the initiative itself still has a critical role to play when it comes to workforce safety and wellbeing.

“I don’t think anyone can dispute the fact that Step Change has been hugely influential in a host of ways. It has in a sense been THE safety rep of the UK’s offshore industry; a crucial role that must be allowed to continue.”

Recommended for you

© PA

© PA © Supplied by DC Thomson

© Supplied by DC Thomson © Supplied by RMT

© Supplied by RMT © Supplied by Allseas

© Supplied by Allseas