Oil and gas accounts for 25% of CO2 emissions from Norway. Quite simply, if the industry doesn’t step up then the country cannot meet its climate targets.

“We have to deliver if Norway is going to deliver”, Simen Moxnes, senior advisor for new energy systems at Equinor, tells Energy Voice.

Our neighbours across the North Sea are already leagues ahead of the UK on offshore electrification – Britain’s tally still sits at zero, nearly 30 years after Troll A received power from shore in 1996.

But not everything on the Norwegian Continental Shelf is electrified, and the requirement to deliver on that comes while power demand in Norway is expected to increase across the board in coming years.

Norway’s parliament has imposed targets for the sector, not unlike the North Sea Transition Deal here in the UK, requiring a cut in emissions of 50% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels – an increase from the previous 40% goal.

That comes as demand for power in the country is increasing.

Presently at around 150 terawatt hours, there are several different projections through to 2024 but it is “not unlikely” demand will increase to 200TWh, says Moxnes.

Upgrades to existing hydropower plants will go some of the way, an additional 10 TWh or so.

“That obviously does not take you all the way to 200, so in that context we believe that offshore wind is the main tool for Norway to improve the power balance.”

Electrification

Norway already had the ambition to develop at least 10GW of wind capacity by 2035 – “the equivalent of three Dogger banks” – and recently trumped it with plans for a huge 30GW by 2040.

Equinor points to the importance that will play in driving down costs through economies of scale, a similar picture seen for reducing prices for fixed-bottom offshore wind in the UK – which the Norwegian firm has had a hand in.

To date, the main concept for electrifying platforms has been power from shore, as seen on the likes of Troll A, Martin Linge and Johan Sverdrup.

But the need to act quickly, coupled with grid capacity connections, and the need to boost supply, has led to some unique challenges.

Equinor plans Trollvind

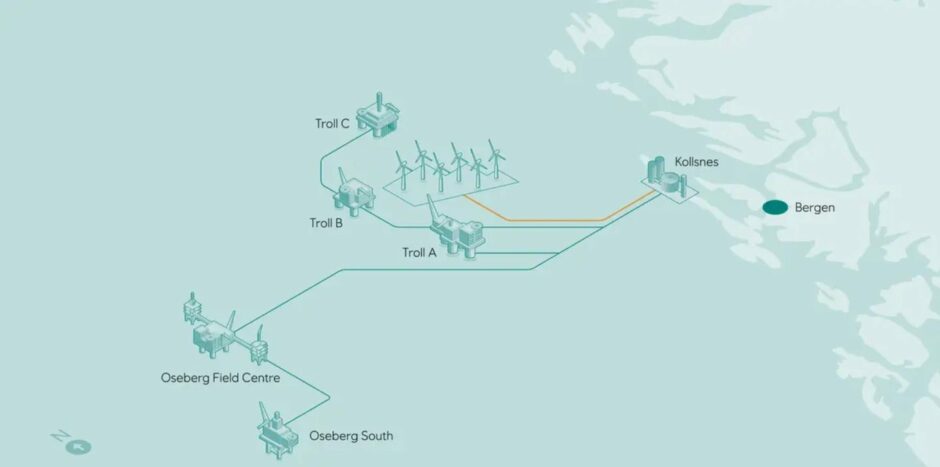

Enter Trollvind: the recently-unveiled plan from Equinor to provide much of the power needed for platforms across the Oseberg and Troll fields.

Moxnes explains that it was the very constraints around grid connections that birthed the concept.

“We have a big refinery at Mongstad, where there are several plants and potential plants for transforming carbon in the future, and we are also look at possibilities for big factories for producing blue hydrogen where we capture the CO2 and store it.

“But we need power for those developments and Kollsnes (near Bergen) is sold out. You cannot get grid connection there until after 2030 after Statnett has upgraded their grid lines.

“There’s a lot of power in that region but the grid capacity to get it from inside the fjords, where the hydropower plants are, is not sufficient.

“So that means that we have seen the restrictions on our own industrial development and we also see that it’s a hinder for other developers that want to develop green industry in that area.”

The solution? Equinor conducted studies in Autumn with a power company on the effects a 1GW offshore wind farm would have on the Bergen/ Kollsnes area.

Results were “better than expected” for strengthening the grid in the region.

“Those results triggered us to see if there is anything we can do to actually do this, and Trollvind was the idea that was given birth, you could say.

“The partners have been quite eager – both in Trollvind itself, and the Kollsnes area which would be the main customer for such a wind farm.”

Problem solving

The idea would involve a combination of floating offshore wind and cable to shore, with excess power sold to areas like Kollsnes.

It means gas turbines can be electrified, which requires major surgery.

“When you electrify these you need to remove all the equipment, put in an electric motor and connected it to a compressor.

“That means you can’t keep the old equipment in backup in case it’s not blowing, so that is my main point, the correct component architecture of being connected to oil and gas is combined with the cable to shore.

“That gives you two things: the possibility to fully electrify and you can also have a considerable size of your wind park – so that you actually can produce excess power, more than we need in your field,to improve the power balance at shore.”

Equinor and partners are targeting a final investment decision 2023 for Trollvind, ahead of potential start up in 2027 if it is progressed.

Projects like this, and the planned 11-turbine Hywind Tampen floating wind farm to power the Snorre and Gulfaks fields, will play an important role in meeting that carbon reduction target for the industry.

Tampen will reduce emissions by 200,000 tonnes per year.

“Typically a gas turbine we use emits 100,000 tonnes,” explains Moxnes.

“So the big picture is we have approximately 80 of those turbines in the Norwegian Continental Shelf and the emissions from the NCS, not including gas treatment plants onshore, is approximately eight million tonnes per year.

“So it shows how important the gas turbines are for our total emissions.”

Exports

Norway is a key supplier to Europe – and the UK – of natural gas, and the future of the energy system is in flux.

Like Equinor, Neptune Energy has a firm eye on investment in the country and assessing what that export picture will be like in years to come.

The firm’s Gjøa platform, for example, will produce about 24 million boe of gas this year, exported directly to the UK via the St. Fergus terminal in the north east of Scotland. Elsewere, Duva recently had a production boost to heat a further 350,000 UK homes.

Managing director for Norway, Odin Estensen, told EV: “Currently, Norwegian energy supplies account for about 20-25% of Europe’s annual gas consumption. We must ensure that we do enough – with current production and via future exploration and development – to maintain our role as a secure energy supplier to Europe.

“About 70% of Neptune’s Norwegian production is gas, and we are investigating opportunities to ramp-up gas production from other fields in our portfolio.”

North Sea laboratory

Developing technology which will help the world decarbonise is a “very important part of life,” says Moxnes, which goes beyond just offshore wind.

CO2 transport and storage is a service Norway hopes to deliver in coming years through its Northern Lights project, as well as scaling up the hydrogen industry.

Blue hydrogen can be ramped up quickly. But using electrolysis to produce green hydrogen to provide the equivalent of just 10% of the gas Norway exports to Europe “would require the same volume as the total Norwegian hydropower capacity”.

“For us it’s a question about building optionality,” says Moxnes in closing.

“We don’t know exactly what Europe wants, whether they want the natural gas and want to decarbonise it themselves, or whether they want blue hydrogen, but we are building optionality so that we can deliver on exactly what Europe needs in the future.”

© Supplied by Equinor/ Simen Moxne

© Supplied by Equinor/ Simen Moxne © Supplied by Equinor

© Supplied by Equinor