For a nation with no producing oil and gas assets, the Faroe Islands is not short on ambition.

Part of the Danish Commonwealth, the archipelago has done a good job of distancing itself from the Scandinavian country’s somewhat hostile attitude to hydrocarbons.

Denmark unveiled plans in 2020 to stop offering new North Sea oil and gas licences, before spearheading the launch of the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA) during COP26.

The coalition of eight core members, including Greenland, is committed to enabling the “managed phase-out” of hydrocarbon production.

Critics of the group point to the fact its associates have little skin in the oil and gas game.

Despite its ties to Denmark and Greenland, the Faroe Islands has been crystal clear that it will not be jumping on the BOGA bandwagon.

When he took office last year, Faroese Minister for the environment, industry and trade, Magnus Rasmussen, issued a clear message – “Don’t expect any significant changes to our current stance on exploration in the Faroes.”

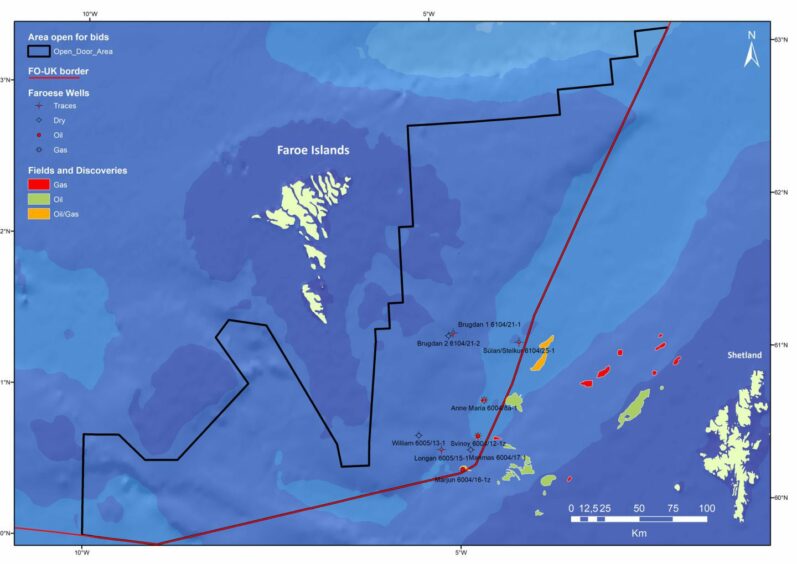

According to the Faroes Energy Industry Group (FOIB), public opinion in the nation, about 210 miles west of the Shetland Islands, remains “overwhelmingly favourable towards the prospect” of oil and gas exploration going ahead, as well as the scaling up of green energy sources.

“There is certainly interest in searching for oil and gas in the Faroese sector, although the extent of this interest is difficult to judge,” Niels Christian Nolsoe, director of Jardfeingi, or the Faroese Geological Survey (FGS), told the national broadcaster recently.

As it stands, the FGS, the equivalent of the North Sea Transition Authority, is inviting energy companies to make out of round bids for licences.

But despite ongoing interest that dates back years, it is not yet known if it will result in actual exploration applications.

Mr Nolsoe said: “The Government has given us the job of selling the Faroese sector to the oil industry in such a way that, if there is some oil and gas in the Faroese subsoil, we assist companies to locate it and to go forward to production.

“What we do is communicate with companies who are interested in Faroese prospects. This is something we have done for many years and this communication is taking place right now.

“We know that there are oil companies who devote resources to focus on the Faroese sector and study the geology to see if they can identify similar structures to those in the West of Shetland area, where there is already substantial production in progress.

“At the FGS, we have our own large and comprehensive research programme to assist them with this. Our geologists know the Faroese geology slightly better than geologists from overseas, so they are in a good position to help in this way.”

Macro influences, including a return to high oil prices, have served as a shot in the arm for exploration and new fields.

Western Governments are working to find alternatives to Russian hydrocarbons, and many are on the lookout for new sources of oil and gas.

Moreover, after a period of stagnation, activity West of Shetland is moving up a gear, with Equinor’s Rosebank field leading the charge.

The Energy Profits Levy, which raised the headline rate of income tax on oil and gas production in the UK, also plays into Faroese hands.

Companies would not have to grapple with a windfall tax, with firms now paying more duty in the UK than they would do in the Faroes, according to the FOIB.

Mr Nolsoe said: “In reality, energy companies are already looking for oil and gas in the Faroese sector. They are allocating workers to this search and to studying the data. And, of course, if they find something worth exploring further, there is a definite prospect that an energy company will apply for a licence to explore in a particular area in the Faroese sector, maybe as soon as the autumn.”

“I don’t know however how certain we can be of this prospect. It could well come to pass soon, or it could take some years. But in the first instance, if something does transpire in this area, the earliest it will happen is in late autumn.”

© Supplied by FOIB

© Supplied by FOIB © Supplied by Jardfeingi

© Supplied by Jardfeingi