The UK Government has made a “clear and significant change” on whether Shell should be allowed to leave the “hazardous wastes” in the Brent oilfield legs in the North Sea.

OPRED, the UK industry regulator, has argued since 2019 the case for Shell to be allowed to leave thousands of tonnes of oil-sediment contents within the structures in place.

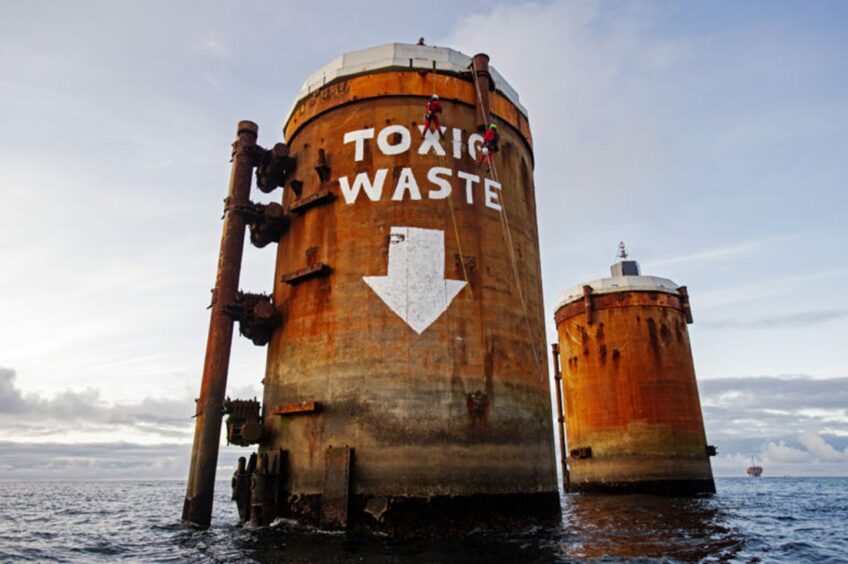

The decision has proved highly contentious, even leading to Greenpeace protests at the famed oilfield in 2019 and 2020, with concerns the cells of Brent Bravo, Charlie and Delta will degrade over years and the contents will spill into the environment.

But, after large opposition from other countries within OSPAR – a pan-European convention requiring removal of oil and gas structures from the seabed – the UK has conceded ground.

During an Offshore Industry Committee (OIC) meeting in Berlin last month – which the UK is party to – it was agreed that the contents are “not part of derogation categories” to the OSPAR convention, and thus require removal or remediation (such as breakdown with chemicals, making the substance inert).

Dumping, derogation and ‘hazardous wastes’

The contents were also agreed by the OIC to be “hazardous wastes” and it would be considered “dumping under the OSPAR convention” to leave them in place.

Ultimately, the decision lies with the UK Government on what will happen, who told the meeting these contents would only be left in place if it was not safe to remove.

It added that the contents “would be removed once the technology was available, and in-situ remediation would also be considered”.

This places a burden on finding a way to remove the contents of the cells safely – but comes as Greenpeace unveiled, at the meeting, Shell studies from 2009 showing it could be done feasibly.

These documents are understood to have never been previously shared with OSPAR.

Shell has long argued that the costs and risks of removal would outweigh the benefits.

Officially, the UK Government said in a statement that this is not a u-turn, stating “OPRED’s decision on the cell contents has not changed” and that it remains in discussions with other OSPAR contracting parties.

A Shell spokesperson said: “Decommissioning Brent is a complex, major engineering project, because of the platforms’ size, age, design, and the harsh environment of the North Sea.

“After more than a decade of research, with more than 300 scientific, environmental and technical studies reviewed by independent experts, our recommendation is that leaving in place the concrete legs and cells is, on balance, the safest, most environmentally sound and technically achievable solution using the decommissioning techniques available today.

“The Brent Field Decommissioning Programme is currently with the UK Regulator for final decision.”

‘Significant change in position”.

It comes as the EU delegation said leaving the cell contents in place would be “environmentally and socially unacceptable to leave thousands of tonnes of oil and other contaminated contents in situ without further explanations or measures”.

People with knowledge of the meeting described it as a significant shift for the UK, which had been minded to leave the legs in place.

David Santillo, an Exeter University marine researcher and senior scientist at Greenpeace, who regularly attends OSPAR meetings, said it is “clear and significant change in position”.

“Initially the UK was convinced that leaving the cell contents in place (i.e. not trying to remove them, in line with Shell’s preferred option) was ‘the best available option’.

“Now they agree that they are hazardous wastes and should only be left in place if they cannot not be safely removed.

“In the short term, the outcome might be the same, but what is fundamentally different is the expectation that Shell should make every effort to remove them if it can be done safely, rather than that the best option was to leave them where they are.”

‘A big deal for the industry’

Another person with knowledge of the meeting, who did not wish to be named, said: “The UK Government has conceded that leaving these contents in un-remediated or untreated is not an acceptable proposition – that is a big deal for the industry”.

“The proposal was, on the Brents, to leave the cell contents as they are, leave in situ. That has full government support, otherwise it doesn’t go to OSPAR.

“It’s only the objections that came in saying this can’t be dumped into the sea legally today, why would it be okay in hundreds of years’ time?

“Over time, the UK’s position has had to shift because of the objections.

“They will argue it’s not a u-turn because they haven’t issued any permits, but the reality is they fully supported this position originally and had to go back on that.”

Arguments around Shell Brent derogation

Brent is not the only derogation application being considered under these grounds and the move means a potential return to the drawing board for parts of decom projects as this sets a precedent.

The Brent field has been subject to protests by activist groups in light of the plans to leave the legs – known as Gravity-Based Structures – in the North Sea.

It is estimated that around 11,000 tonnes of oil lie within the structures, however Shell states that this is not free-floating but bound to sediment comprised of sand, grit and water.

Shell argues it will take “centuries” for the Brent legs to degrade as the sediment is encased in concrete, while the safety risk and cost of removing these giant structures would outweigh any environmental benefit.

The Brents are among the older installations in the North Sea and the GBS, which the oil giant said were not made with removal in mind, are no longer used in construction.

OSPAR recently set a deadline of 2024 for creation of a comparative assessment methodology, designed to inform the Brent decision and others like it.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Greenpeace

© Supplied by Greenpeace