In Part One of this celebration of Offshore Europe, we closed with news that the brand new Aberdeen Exhibition and Conference Centre would be ready for the 1985 show.

And it was … for founder David Stott and for Aberdeen too. Then the news got even better; Prime Minster of the day, Margaret Thatcher, agreed to open the 1985 event.

“At last, we could hold our heads up high and know that we could compete with anybody,” David said of the venture that had started 12 years earlier in a tented “village”.

The overall cost to Spearhead of the AECC had been £1.3million.

“It nearly bankrupted the company, now mortgaged to Grampian Regional Council,” he recalled.

“But we clung on through the downturn of 1986-87 and stability was restored when we brought in the Society of Petroleum Engineers as one of our partners in 1988.”

It was in reality far more dramatic than that and is indelibly signatured by the first global oil price crash; not merely a downturn.

1985 began badly for the North Sea with the Iran-Iraq War breaking out in March, plus a row was building between Middle East-centric Opec and other oil producers.

Not that this stopped the ’85 Offshore Europe in September from becoming the success it proved to be.

Weeks later, in November, global swing producer Saudi Arabia made the decision to defend Opec market share.

Instead of pushing prices down, perversely, this achieved the opposite, with West Texas Intermediate setting a new record of $31.75 on November 20.

Hardly a portent of disaster?

Ah, but on December 9, Opec met again and determined to wage war with non-Opec. The switch to a production free-for-all within the cartel became the spark that finally lit the fuse that blew price controls apart that resulted in the crash of 1986.

Brent dropped below $9 per barrel by mid-1986 while cartel production hit 20million bpd. All hell broke loose in the North Sea. Some 6,000 out of more than 28,000 offshore jobs plus many onshore evaporated.

Oilcos slashed exploration budgets by 30% to not much over £1billion; and capital spending was chopped back £500,000 to £2.3billion (WoodMac).

Aberdeen was in panic and 40% of drilling rigs were forced into stack.

The North Sea was in agony, but cheap fuel was just what was required by the Thatcher regime to fuel Britain out of the recession it was struggling with.

As New Year revellers straggled back to work in 1987, they returned buoyed by the pre-Christmas news that Opec led by the Saudis wanted oil back up to at least $18.

If the group had not in the past acted as one, then it was certainly behaving like a cartel now, including engineering a reference pricing formula in order to achieve adequate future prices.

Reality was that the North Sea industry still struggled; it needed higher oil prices than Opec members required to live on.

Indeed talk turned to abandoning some fields, unless new ways could be found to produce them more cheaply. And so attention turned to what could be achieved on the drilling front, especially deviated drilling; plus developing reliable downhole pumps.

UKOOA director general George Band warned of the need for big change at 1987’s Offshore Europe and spoke of making greater use of subsea technology, better project management and utilising spare capacity within existing infrastructure.

Band said there were ample discoveries waiting to be developed and observed that orders for 27 new UK platforms were in prospect over the period 1987-88, though mostly small Southern Gas Basin structures.

Grampian Region convener, Geoffrey Hadley was optimistic in his Offshore Europe message: “There is a lot of life and activity still to come in the North Sea and this year’s exhibition and conference will, I am sure, project an image of determination from an industry growing in confidence again, after the downturn brought about by the price recession.

Perhaps the biggest boost was when energy minister Peter Morrison announced Shell’s Kittiwake field development and that it would create around 2,500 new construction jobs at peak.

It was just the kind of North Sea messaging that a stressed-out David Stott and his team and still reeling Aberdeen badly needed.

And so the UK’s flagship energy industry rolled into 1988 a tad more confident about its future. Moreover, that year’s bag of discoveries was decent enough – Harding (Britoil), Saltire (Occidental) Nelson (Enterprise), while Shell bagged Shearwater and Heron.

But, on the evening of July 6 that year, the Occidental-operated

Piper Alpha platform blew up, killing 165 of the 226 persons on board, plus two crew from the standby vessel Silver Pit perished during rescue efforts. The tragedy shook the industry to its foundations.

Thankfully the next Offshore Europe was not scheduled until September 1989 and had been intended as a perfect platform to mark the North Sea industry’s 25th anniversary. It ended up being somewhat overshadowed by the Piper Alpha aftermath.

Disaster notwithstanding, by the end of 1988, 36 oil and 26 gas fields had been developed with a cumulative production of 9billion barrels of oil and 23.5trillion cubic feet of gas.

Projections of future developments made by UKOOA then suggested that, over the ensuing 25 years the industry “was likely to drill in excess of 2,000 exploration and appraisal wells and to develop between 100 and 300 new fields”.

No wonder Aberdeen was by then self-branding itself as Europe’s Oil Capital.

However, this claim was rubbished at the 1989 Offshore Europe by Ian Wood, founder/chairman/CEO of the local Wood Group and John D’Ancona, director general of the Government’s catalyst Offshore Supplies Office

Wood described the Granite City as just a “branch office” in the wider oil and gas game. He warned then and many times since that Aberdeen had too few serious players when it came to exportable technologies.

In a keynote address he said: “I believe the UK industry’s participation in the international market is woefully short of what it should be, bearing in mind that the UK Continental Shelf has been the principal proving and developing ground for the world offshore industry during the last 20 years.”

D’Ancona (AKA the Maltese Falcon) was scathing: “London is the oil capital of Europe, because this is where major decisions are made and because this is where the headquarters of the major oil companies and contractors are … and the Government. In fact a lot of them aren’t even made in Britain, they are made in America,”

Criticisms aside and helped by publicity at the 1989 show, the foundations of a hoped for major centre of oilfield technology excellence – Aberdeen Offshore Technology Park (AOTP) – were set as part of a drive to achieve the critical mass that North Sea leading lights like Wood said was essential to long-term prosperity.

Sadly, offshore, industrial relations were at a low ebb. Trade unions wanted a North Sea Continental Shelf Agreement with the operators, but ultimately failed in the attempt. Workers were increasingly restless.

But this paled against the drama ignited in the Middle East when, at 2.00am on August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait.

However, the invasion of Kuwait whipped up massive international opposition and the West set about making an example of Iraq’s leader Saddam Hussein by mounting first Desert Shield and then Operation Desert Storm to evict his troops from Kuwait.

Meanwhile, in the UK, there was the political assassination of Margaret Thatcher, with John Major becoming PM on November 27 1990.

In the North Sea, haunted by Piper Alpha, operators were much preoccupied with satisfying the 113 recommendations made in the Cullen Report on the tragedy.

A core recommendation, the newly created Offshore Safety Division of the Health and Safety Executive, was launched on April 1 1991 with Tony Barrell as its first supremo.

As for that year’s Offshore Europe and aside from war talk, oil prices, North Sea safety, surely the high point was energy secretary John Wakeham’s statement regarding possible relocation of the Department of Energy’s Petroleum Engineering Directorate (70 jobs) to Aberdeen to crank up flagging North Sea activity.

On the opening day of the show, Wakeham said the weight of evidence stacked against the case for relocation was “substantially stronger” than arguments presented by Scottish Enterprise and other lobbying parties.

Ian Wood retorted: “This is not just for Aberdeen’s benefit or for Scotland, but for the UK as a whole.”

In the event, Aberdeen won the battle for the PED relocation. Just as well as, in our June Edition, the 1990s became a very rough time indeed for the North Sea.

Recommended for you

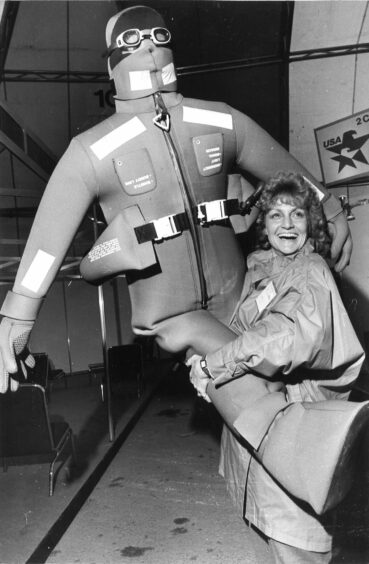

© Supplied by AJL

© Supplied by AJL

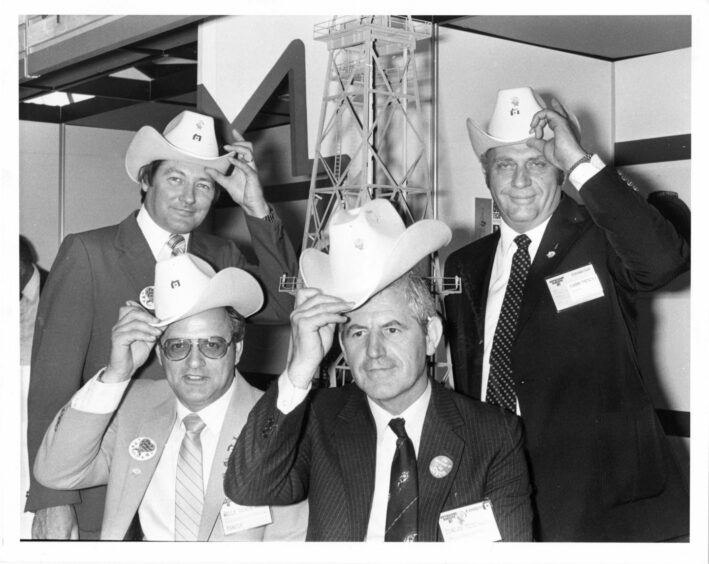

© Supplied by system

© Supplied by system © Supplied by Sysyem

© Supplied by Sysyem