Despite the ups and downs of the energy transition, it’s likely North Sea oil and gas production will be with us even in a net-zero 2050.

But getting there will require sweeping changes to infrastructure, not least to tackle the industry’s most pressing concern – removing the emissions associated with producing hydrocarbons.

Under the North Sea Transition Deal (NSTD) signed in 2021, the sector has committed to achieving reductions in upstream production emissions of 10% by 2025, 25% by 2027 and 50% by 2030, against a 2018 baseline, all of which would position it towards becoming a “net zero basin” by 2050.

It amounts to a reduction of around 60 million tonnes of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, around 15 million tonnes of which would come from the period to 2030.

The latest Emissions Monitoring Report from the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) suggest progress is being made. Overall GHG emissions have fallen from 18.8 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) in 2018 to 14.3 million tonnes in 2021 – a reduction of around 21.5%.

Illustrating the lumpy nature of that path, the carbon intensity of the sector rose also slightly in 2021 to 20.81kg CO2/boe (though this is largely due to maintenance work and remains below 2018 levels).

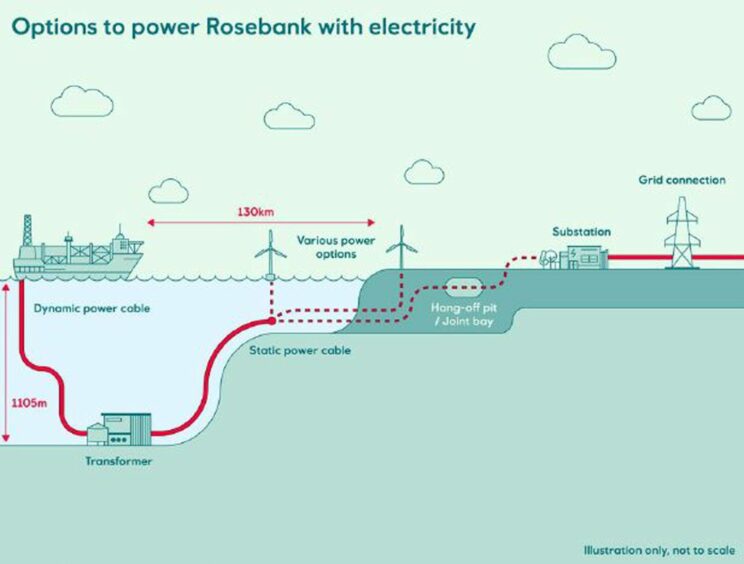

Much of the heavy lifting towards 2050 requires large-scale electrification – hooking up platforms to run on cleaner sources of power, whether from offshore wind or the national grid.

Alongside its emissions targets, the NSTA says it expects “real progress” on this front over the next five years, with at least two electrification projects commissioned by 2027.

And while it is pleased with the sector’s pathway, it found that the sector is “not on track” to meet the 2030 target on its current “business as usual” trajectory.

North Sea emissions: Decommissioning makes path easier

Despite that warning, Welligence’s vice president of North Sea research David Moseley expects a fairly manageable trajectory for industry in the near term.

“A lot of that 2030 target will be achieved through abandonment of facilities,” he told Energy Voice.

“If you look at when fields are coming offline in the North Sea – that alone and nothing else, essentially a do-nothing scenario – you’ll see most of that target being met anyway.

“Our view is that target doesn’t appear to be too challenging, provided fields do come offline broadly when we expect, and when they go cash-flow negative.”

This assessment is based on the shuttering of around 26 production hubs across the basin over that time. Even still, Welligence acknowledges the need for “significant investment” in equipment and tech at these hubs to meet sector goals.

Wood Mackenzie expects a similar result. “In our base case at the moment we have them just hitting the 2030 target,” noted principal analyst for North Sea upstream, Jessica Brewer.

“We don’t include electrification in our base case, so that’s without electrification. The big driver to meeting our case is just field cessations. If fields cease – especially because it’s all mature kit – that helps.

“I think what we’ve seen so far is a lot of what we would call low hanging fruit, being done which has helped maybe reduce some of the flaring, methane, operational changes.

“The big gain would be if you could get electrification to work, you’d be a lot more likely to meet that target.”

Yet both forecasts come with caveats. Welligence’s head of energy transition Juan Agudelo cautioned that the outlook is changeable, as operators tend to have “a limited view” of the development of assets, with plans that have to account for changing policy and price environments.

“What if the economic limit of that facility extends? That creates a delay in when those emissions will be removed.

“Banking [only] on reducing emissions from the facilities being abandoned might be risky.”

Ms Brewer too pointed to a multitude of variables which could extend or shorten the life of such fields, not to mention that much of the commercial side of electrification – how much power costs and what impact this has on opex – has yet to be fully defined.

Yet for many operators, those may still be worth bearing in order to justify continued production. BP, Ithaca Energy and Equinor, for example, are teaming up to work on solutions for their fields west of Shetland.

“There might be an economic cost to this – but if that gives you that kind of social licence to keep operating, that’s maybe the difference,” she said.

While the pace of change is up for debate, WoodMac expects the overall production intensity of the basin will fall from around 20kg CO2e/boe at present to 17kg by 2030 – even with the addition of new, pre-electrified fields.

“One of the drivers of that is even though we don’t assume that the likes of Cambo and Rosebank would be electrified [immediately], they still come with a lot lower intensity than the more mature assets.

“As well as efficiency gains, those assets will have relatively high throughput. So I think electrification is just one part of that bigger puzzle,” she added.

Windfall tax impact

Alongside commodity prices, policy is another crucial variable. While it hikes headline tax rates, the government’s Energy Profits Levy (EPL) also offers generous incentives for decarbonisation – meaning firms spending £100 on projects such as electrification could receive up to £109.25 back.

Even still, Mr Moseley does not expect these to be transformative. “Electrification isn’t something that would work just because of the impact of the EPL,” he said.

“It’ll help, but companies need electrification to work on its own on their assets, regardless of whether the EPL is there or not.”

Those incentives will of course aid greenfield projects such as Cambo and Rosebank, but he sees this very much as a “benefit” rather than a differentiating factor.

“There are synergies between the EPL incentives and electrification, but it is very much a sort of benefit for companies who are in those projects.”

Mr Agudelo agreed, but suggested the time-limited availability of these drivers may still help to create a “window of opportunity” for operators to make capital-intensive investments.

“Having those incentives now and the need to decarbonise will at least make companies try to find the solutions applicable to their assets now. You don’t know long those things will be available – if you don’t take advantage of them now, they might not be available in the future.”

Hurry up and wait

“The question now with all these initiatives is how successful they will be,” posits Mr Agudelo.

“We are in a moment of announcements and MoUs, licensing rounds – how much of it will materialise?

“I think the economics of a lot of these projects are still a big question mark for all the different players. They’re navigating how to decarbonise their portfolios while at the same time making reasonable economic decisions and investments.

“They’re doing the right thing in general, I think, but time will tell how successful things will be.”

The NSTA has also said its 50% goal is a minimum – and that industry should strive to reduce North Sea emissions by 68% by 2030 (a figure endorsed by the Climate Change Committee).

There may be other tools in its arsenal, too. Former head Andy Samuel last year suggested the regulator could adopt a “name and shame” approach for the roughly 20% of operators who were seen not to be putting their weight behind decarbonisation.

In the meantime, other electrification targets are looming.

“The NSTD was targeting two by 2027. We’re now midway through 2023, and we haven’t seen one sanctioned yet, so that could be a challenging time frame,” added Ms Brewer.

“I think by the end of the decade would be feasible, wherever it may be, but you’re getting into a time frame where it’s getting challenging.

It chimes with the view of developers too, In a recent panel on the Innovation and Targeted Oil and Gas (INTOG) round, one project backer said it would be “exceedingly hard to build a project and business case” starting today for delivery by 2030.

So, while the industry’s current trajectory offers it some flexibility, there remains no time to lose in speeding projects through planning and approvals and towards final investment decisions (FID).

Without this effort, any progress on North Sea emissions beyond 2030 could start to stall.

“The challenge for some of the projects that are on stream is this takes time – and every year it doesn’t happen it’s another year of production that’s been lost that could be electrified,” she noted.

“Every year it doesn’t happen will make the economics look more and more challenging.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by DC Thomson

© Supplied by DC Thomson © Supplied by Equinor

© Supplied by Equinor