In Part Three of our look through the history of the North Sea and Offshore Europe, this time through the 90s.

We find that Aberdeen remains spooked by the drastic impacts of the 1986 oil price crash on the North Sea, with operators struggling to rebuild momentum even after five years.

Fortunately, the battle to relocate a key government offshore engineering unit north to the Granite city had succeeded.

Indeed the Petroleum Engineering Directorate’s relocation proved to be a catalyst to a string of operators and contractors moving their people to Aberdeen.

Numbered among them were BP, which finally shut the former Britoil offices in Glasgow, Chevron, Conoco, Total and Foster Wheeler, which formed a joint venture with Wood Group.

However, this was not enough to turn the tide of gloom and huge job losses. Something really drastic was needed to reboot exploration and further developments activity.

Led by the UK Offshore Operators’ Association, a team effort was initiated. CRINE – Cost Reduction Initiative for the New Era – was born in 1993. Its mission, to slash – spending and get a new wave of projects moving.

This was the beginning of the era of alliancing and partnering between operators and contractors, and contractors with contractors.

CRINE was about creating competitive advantage so the North Sea could compete successfully for capital against other energy provinces that were looking increasingly more attractive.

The first objective was to slash the capital cost of a typical development by 30% and then push it to 60%. Then, from around 1995, the crusade would move on to hacking operating expenditure by similar levels while claiming asset integrity and safety would not suffer.

All great fodder for conferences like Offshore Europe, with founder David Stott determined to be successful come what may.

Given the post ’86 crash predictions of tumbleweed on Union Street, David should have been worried. But he claims he wasn’t.

“I was probably more optimistic than I should have been,” reflected David in a recent chat.

“The oil companies were still making money; though the contractors and supply chain in general were going through tough times, to put it mildly.”

Offshore Europe in the 90s had become a key North Sea debating chamber. Yet the oilcos never exhibited, unlike alter-ego Offshore Northern Seas in Norway where they were compelled to by government.

SPE as dream partner to Offshore Europe in 90s

“John D’Ancona, director of the Offshore Supplies Office, tried to persuade them to do that,” recalled David. “So BP took a small stand at one or two of the shows. But most never did.

“It was tough. Having built Aberdeen Exhibition & Conference Centre, we were in hock to Grampian Regional Council, which had a lien on our shares.

“Reality was that it was only when the Society of Petroleum Engineers took a stake that things started to get better.

“We secured a very good deal because, though the SPE held 50% of the show, we had the management fee; in other words we were still running Offshore Europe and did extremely well.

“Importantly, the Grampian Region lien was released and this enabled us to start shows in other places, which we wouldn’t have been able to do prior to the SPE arrangement.”

And so, with the SPE in as a dream partner with an industry that at last had the bit between its teeth, Offshore Europe was, in the 90s, in an excellent position to capitalise on the opportunities.

It helped greatly that BP made two significant West of Shetland oil discoveries – Foinaven and Schiehallion – and quickly embarked on fast-track development of the former.

Other developments were stimulated by positive tax changes, key among which was the decision to reduce PRT from 75% to 50% on existing fields and to abolish it on new developments. An early result was BHP’s Liverpool Bay cluster project.

So was it boomtime again?

The stark position of the crucial fabrication sector was that the UK’s yards were in deep trouble. The issue was allegedly unfair competition from other EU yards, particularly in Italy and Spain.

Brown & Root and McDermott decided to merge the Nigg and Ardersier yards to create BARMAC.

Despite the negatives, projects were secured; like Enterprise Oil’s flagship Nelson development, Dunbar and Ellon (Total), and Chevron’s Moray Firth heavy crude discovery, Alba.

BP gave green lights to Andrew and Harding; then followed these with news of the £1.6million Eastern Trough Area Project – a cluster comprising BP-operated Mungo, Machar, Monan and Marnock; and Shell’s Egret and Heron finds.

Yet another CRINE classic was the Britannia gas/condensate development based on a single huge platform.

In 1997 and unbeknown to most Aberdeen folk, another slump was on its way.

Brown plans North Sea tax raid

That year, analysts at Wood Mackenzie forecast that overall North Sea production would reach new highs, with oil lifting 7% to 6.47million bpd. Of this, Norway would account for 3.43million, while the UK would come second at 2.47million, a new record in itself. Gas would boom too.

However, as 1997 advanced, oil prices began drifting downwards, even as the Northern winter was setting in. The root of the price problem was claimed to be that Japan and Korea, in particular, were sliding into recession, as was Brazil.

There was talk of global recession.

The West went through the ritual of blaming OPEC for raising output in November that year, plus cheating on quotas.

The first week of 1998 was OK, oil prices reaching $16.41. But then the drift into a full-blown slump really set in. Mid-Mach saw Brent around $12. It then picked up a bit before again heading downhill.

By December, the North Sea benchmark crude had dropped below $10, reaching an all-time low in real terms of $9.55, while North Sea projects were at that time planned at around $14-16 per barrel.

To make matters even more complicated in Britain, gas prices were lousy too.

A dreadful crisis was developing. It was slow-burn and initially barely noticed in ABZ.

Economic crash: ‘The Dead Sea’

The second global oil price crash was quietly touching down.

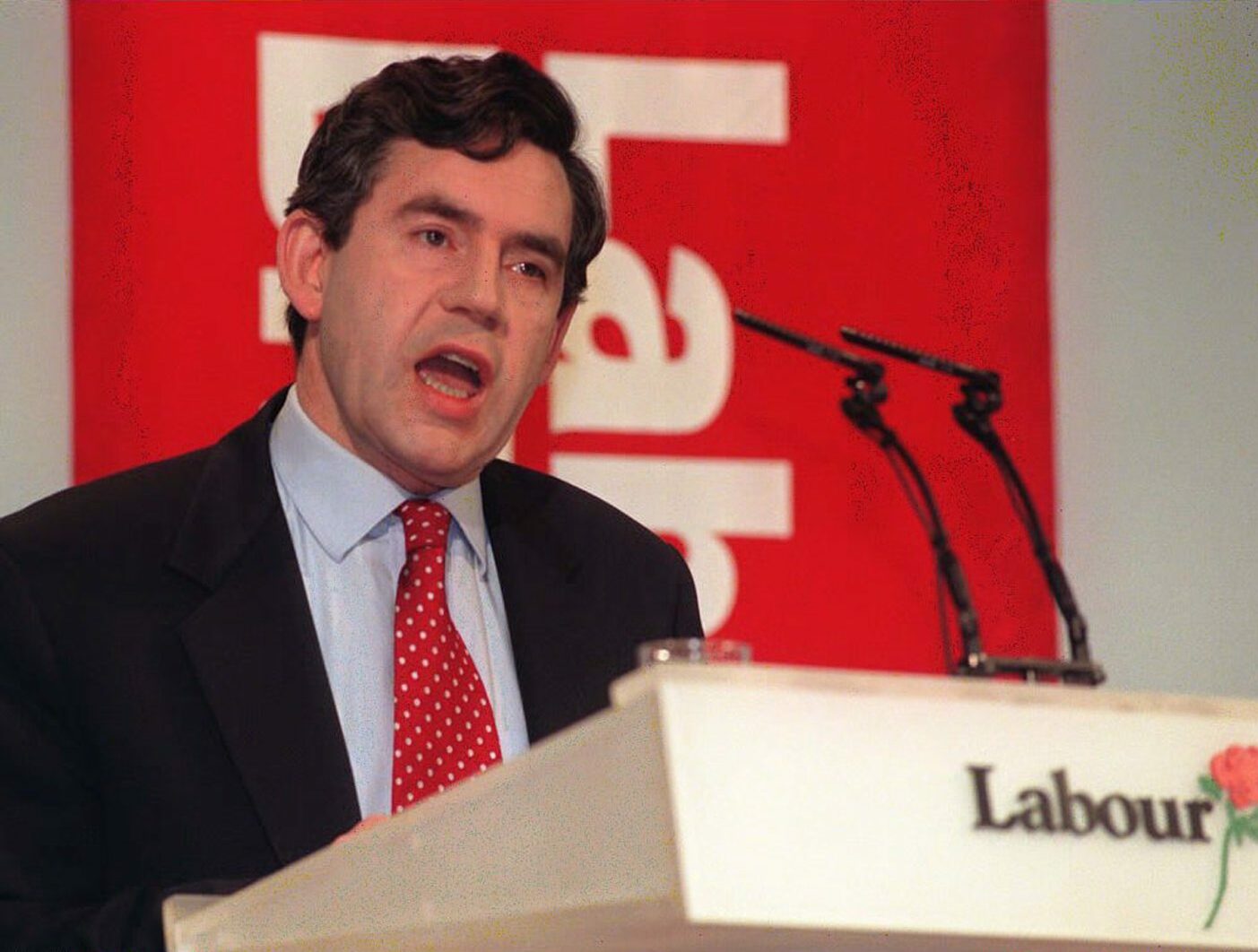

Hard to believe that, just months earlier in March 1998, then UK chancellor Gordon Brown was plotting a tax raid on the North Sea.

That instantly riled the operators and BP cancelled the first stage of its West of Shetland Clair heavy oil project. News of that decision broke on May 26.

On June 29, The Press and Journal waded into the fray by publishing its protest supplement, “The Dead Sea”, which even made it to the floor of the UK;s House of Commons.

Around the time the dispute with Brown was at its zenith, BP announced it was to merge with Amoco to create the third largest oil major in the world, with a market capitalisation of $130billion. The deal was worth $48.2 billion and set off a landslide of major mergers.

It took until September 7, 1998, before Brown cancelled the raid.

Conflict turned to co-operation with the creation of the Oil and Gas Industry Task Force (OGITF) to fight the slump.

It was set up with the ready-made workgroups and thinking that had been developed via CRINE and CRINE Network and took centre-stage at the 1999 Offshore Europe, which by then had evolved significantly further in terms of ownership.

Now, buried in the history of Offshore Europe is a deal that was struck four years earlier in 1995 when the Stott family was approached by an American company keen to buy out their stake in the show.

“The company was PGI from Washington,” said David. “They persuaded me into thinking that this was the right thing to do.

“I’ve reflected on this sale since. I shouldn’t have sold. However, there’s no point in worrying about that now!

David found himself bound to the deal but also found working for the buyer “constraining and difficult”.

“They wanted Offshore Europe for the cash that it generated and there was nothing left for us to be able to develop the show further.”

David remained associated with OE for a number of years before exiting for good.

Many in the industry, let alone Aberdeen appeared unaware that Spearhead became incorporated under the name PGI Europe as of November 1, 1995; right in the thick of the North Sea CRINE wave.

And then, eight years later, Reed Exhibitions was to acquire the PGI stake, the deal being announced on September 3 at the 2003 Offshore Europe, just as the longest bull-run in the history of North Sea oil was getting under way.

The good times had returned.

Read part one of our series here and part two here.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by BP

© Supplied by BP © Supplied by AJL

© Supplied by AJL © Supplied by AJL

© Supplied by AJL © Supplied by AJL

© Supplied by AJL © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © Supplied by AJL

© Supplied by AJL