Expectations for North Sea platform electrification are high – but with the clock ticking, questions persist over the cost and feasibility of plugging in aging assets.

The North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) says eight fully electrified assets are required by 2030 to meet its central case for emissions reduction – a goal it makes clear must be achieved “as a minimum.”

It has separately said it hopes for at least two electrification projects to be commissioned by 2027.

The sector appears to be rolling up its sleeves, with several collaborative and individual efforts launched by operators in recent years.

But the viability of these schemes depends on a number of variables from commodity prices to cessation of production (CoP) dates, to grid connections, all of which cast a shadow of uncertainty over the regulator’s eight-asset target.

Count down from 11

There are currently 11 major offshore facilities with some form of electrification scoping in progress, according to Welligence Energy Analytics.

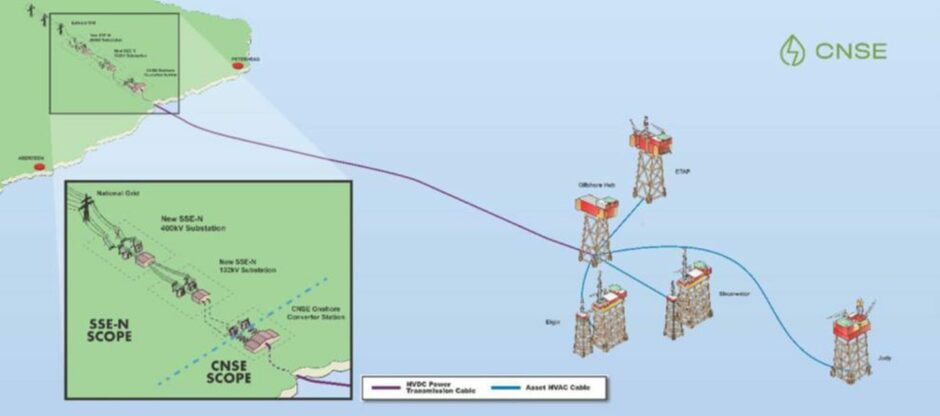

One scheme – Central North Sea Electrification (CNSe) – backed by TotalEnergies (XPAR:TTE), Shell (LON:SHEL), and BP (LON:BP), could help to decarbonise four key production hubs: BP’s ETAP, TotalEnergies’ Elgin, Harbour Energy’s (LON:HBR) Judy and Shell’s Shearwater.

Another could link West of Shetland assets such as Clair, as well as future developments at Rosebank and Cambo, with power potentially sourced from a local onshore wind farm.

Meanwhile separate efforts could see hook ups for the forthcoming Avalon FPSO, as well as Buzzard and Captain.

Most recently, TotalEnergies revealed plans to electrify its Culzean field, work on which is slated to begin as early as 2025 in the wake of a final investment decision pegged for later this year.

These make for a healthy pool of assets – though not all are likely to be long-lived.

Given the high upfront costs, facilities will need “a sufficiently long productive life, at least into the mid-2030s, to make such an investment economically viable,” says Welligence VP for North Sea research David Moseley.

“With over 30 production hubs including over 100 tie-back fields expected to cease by 2030 in our base case view, timing of electrification is critical as the opportunity pool diminishes.”

It was a thought echoed by Wood Mackenzie research director for North Sea upstream Gail Anderson who told an Offshore Europe presentation there was “real doubt” over the viability of Central North Sea targets given it expects most will cease producing before 2040.

What’s more, the consultancy estimates that 80% of resources around these assets have already been produced – leaving less than 600m barrels of oil equivalent (boe) remaining in the area.

Barely breaking even?

If longevity is one concern, sourcing capital is another.

“Upfront capex will be a barrier for many operators,” Mr Mosely added.

“All but one of the 11 facilities highlighted are operated by either majors or large independents that have the ability to fund such projects. However, for smaller operators of other facilities across the North Sea, there may be a lack of necessary capital, or an inability to deploy it in the timeframe required.”

Some incentives are on offer to assist. The government’s Energy Profits Levy (EPL) offers generous rebates for offshore decarbonisation projects – meaning firms spending £100 on schemes including electrification could receive up to £109.25 back.

However, Mr Moseley has previously dismissed these, noting that rebates are – on their own at least – not enough to justify the outlay required.

“It’ll help, but companies need electrification to work on its own on their assets, regardless of whether the EPL is there or not,” he told Energy Voice in June.

Other long-term signals will be more important. “For upstream players to see a viable case for electrification, there needs to be greater certainty on both long-term Emissions Trading System (ETS) pricing and gas prices, with both of these liable to have a significant impact on project economics,” he added.

“Overall confidence in electrification projects providing a return on investment, or simply breaking even, appears low.”

David Cunningham, Director for renewables, cleantech and sustainability at Gneiss Energy was more emphatic.

“Expensive retrofit electrification for near end of life offshore oil and gas facilities makes little economic or carbon-saving logic,” he told Energy Voice.

“The money would be better spent directly decarbonising in other areas such as scope three emissions from the burning of fossil fuels.”

Don’t think twice

Despite doubts from analysts, companies remain staunchly behind plans.

Backers of CNSe are targeting Q1 2027 for the start of onshore construction and offshore installation, with the goal that the project will be ready for first power in December 2028.

BP, Ithaca Energy (LON: ITH) and Equinor (OSLO: EQNR) too have been working for nearly a year on their joint plans West of Shetland, estimating that full electrification would require in the region of 200MW of capacity.

On the supply side, Flotation Energy has filed paperwork for a 560MW floating wind farm linked to both offshore assets and the mainland grid, offering a route for CNOOC’s Buzzard platform, among others.

Meanwhile net progress on offshore emissions reduction has been positive. So far the sector has slashed CO2e output by some 23% between 2018 and 2022, exceeding its target of 10% by 2025 and within touching distance of its 25% reduction target for 2027, according to the regulator’s latest Emissions Monitoring report.

Analysts are confident the sector’s next milestone – a 50% reduction by 2030 – is achievable, though this will be largely thanks to decommissioning and optimisation, rather than a transformative roll-out of electrification.

With that in mind, the NSTA’s pressure to reach its eight-asset “central case” appears to be as much about future-proofing the basin – and possibly taking the fight for low-carbon production to neighbouring Norway – as it is about hitting emissions goals.

Emphasising its perceived urgency, the NSTA’s emissions report warns that industry “cannot afford to let plans slip” and “must focus on punctual delivery of these significant emissions reduction projects” to make sure their full potential is realised.

With most assets only getting older, its messaging suggests investments need to be made quickly – or else they may not be made at all.

© Supplied by Primat Recruitment

© Supplied by Primat Recruitment © Supplied by CNOOC

© Supplied by CNOOC