© Supplied by NSTA

© Supplied by NSTA A new report from the UK’s offshore regulator examines the state of seismic technology for carbon storage and the difficulties in gathering data alongside the expansion of new wind farms.

With up to 100 projects in UK waters expected to be required to meet carbon storage targets, the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) says the coming decades will involve “completely redeveloping” large areas of the UK’s geological basins and subsea areas.

However, it found that full co-location of carbon storage sites with wind farms is in many cases “impossible”, given spatial requirements and the need for ongoing seismic monitoring once CO2 is injected.

The report, ‘Seismic Imaging within the UKCS Energy Transition environment’, looks at the role technology can play in studying the seabed and assessing potential uses in different areas of the North Sea.

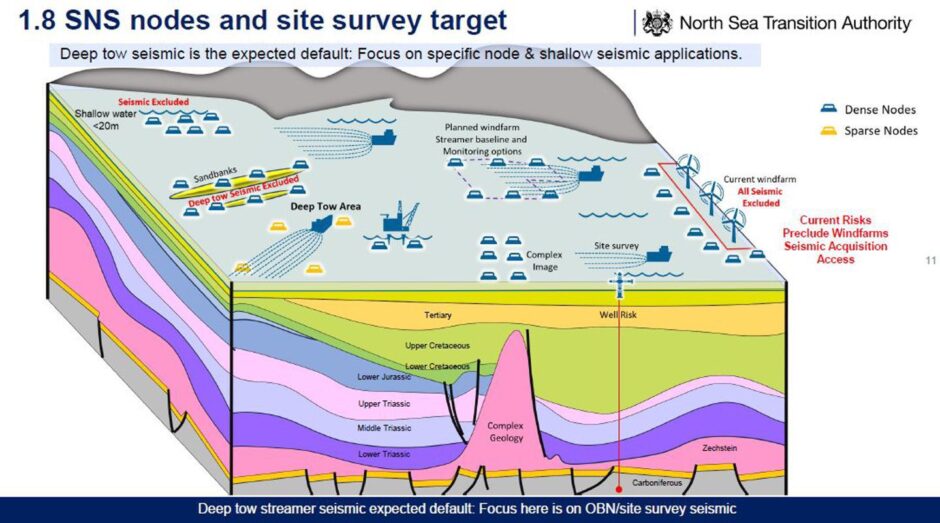

In particular, the report points to a high concentration of storage activity in the southern North Sea which could lead to issues surrounding future seismic acquisition.

With increasing competition for seabed space, the NSTA says its “strong recommendation” is for modern seismic operations to be conducted before further wind farm development is undertaken “as future intra-windfarm seismic operations will be complex, difficult, costly or even operationally impossible.”

Moreover, it finds that full co-location of carbon storage sites or oil and gas closures with windfarms is also “impossible”, as some seismic monitoring would be expected throughout the life of the store.

“Whilst seabed seismic can help to acquire images closer to the edge of a windfarm, it is unlikely any form of seismic equipment will be able to access within the tight confines of current turbine layouts,” it adds.

Currently-planned CO2 sites are covered

The report follows the UK’s inaugural carbon storage licensing process, in which 14 companies secured 21 storage licences across various areas of UK waters.

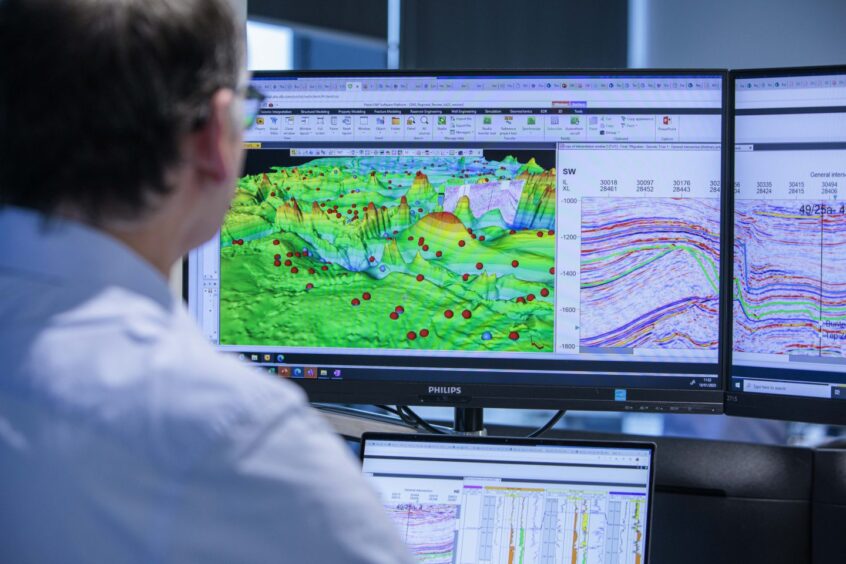

It considers focuses on various seismic technologies and how they could be used to explore potential sites and or carry out ongoing monitoring.

In positive news, it finds the majority of potential UKCS storage area areas mooted so far are covered by legacy oil and gas 3D seismic which, with some modern reprocessing, will enable pre-development site characterisation.

But further surveys will also need to be carried out before CO2 injection, with several options available at varying costs and fidelity.

Whilst some techniques such as ‘streamer seismic’, may be more cost-effective, they have downsides due to a larger footprint and their difficulty in accessing more developed areas – such as between wind turbines.

“The focus will increasingly be on selections of techniques bespoke to each project which can minimise operational footprints (e.g. Ocean Bottom Seismic), enhance resolution where it is needed most, make the best use of early baseline data, take full advantage of improvements in processing, and exploit passive signals thus obviating the need for extensive operations,” the report authors state.

In the longer term, 4D seismic – monitoring which also shows subsurface changes over time – is likely to prove to highly useful, but is expensive and comes with additional environmental impacts.

Multiple demands

The findings echo a long-running dispute between BP and Orsted over their separate proposals for an area of seabed off Yorkshire.

Orsted (CPH:ORSTED) intends to build its 180-turbine Hornsea Four wind project in the area, while BP (LON:BP) sought to use the subsurface Endurance reservoir for carbon storage.

Both schemes were awarded preliminary licences by the UK Government over a decade ago, when it wasn’t thought the overlap would be a problem, with their disputes centering on the use of ‘seismic streamers’ to monitor the reservoir, which risked getting caught in the turbines.

The stalemate was eventually broken this summer, with BP’s objection removed, but further disputes are a possibility as multiple interests compete for development space.

The report voices support for the development of smaller footprint active or passive technologies and greater technology development, as well as better long-term spatial and temporal planning.

But while technology is vital, the report authors also point to “early and open discussions” as the best way to manage competing demands.

Professor John Underhill, Aberdeen University’s Director for Energy Transition, said: “Carbon storage in subsurface reservoirs in saline aquifers and depleted oil and gas fields provides a means by which to lock-in industrial emissions that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere. For sequestration to be successful, it is imperative to select and monitor the best stores to ensure that they are safe and do not leak.

“Crucially, the NSTA report also documents the significant challenges resulting from the competition for offshore areas, particularly where fixed and floating wind farms impede seismic data acquisition.

“The report is a timely reminder of the urgent need for marine spatial planning to maximise the use of offshore areas, if the country is going to meet its net zero targets.”

Crown Estate CCUS and hydrogen technical lead Adrian Topham also welcomed the findings, adding: “The Crown Estate is committed to building that body of evidence, through our pioneering work to digitally map existing and future demands on the seabed out to 2050 and through the Offshore Wind and CCUS Co-Location forum established to provide strategic coordination of co-location research and activity and help maximise the potential of the seabed for these two critical activities.”