In its election manifesto, Labour successfully concentrated its fire on high energy bills as a key issue of electoral discontent. They laid the blame on the Conservatives’ neglect of onshore wind, solar, nuclear and energy efficiency as amplifying the country’s high level of dependence on gas imports. This, the manifesto said, left working people “vulnerable to dictators like Putin.”

As a result, Labour intends to pursue energy independence, which is a great phrase – albeit more Trump than Starmer.

But energy independence is something we all want… surely?

Import dependency is not so bad

In the traditional sense, energy independence means a surplus of energy commodities, allowing a country to more than meet domestic demand. This keeps domestic consumers and businesses insulated from the wild price swings of international markets, generated by the machinations of dictators, speculators and cartels.

Only it doesn’t, at least not in market economies open to free trade, such as the UK.

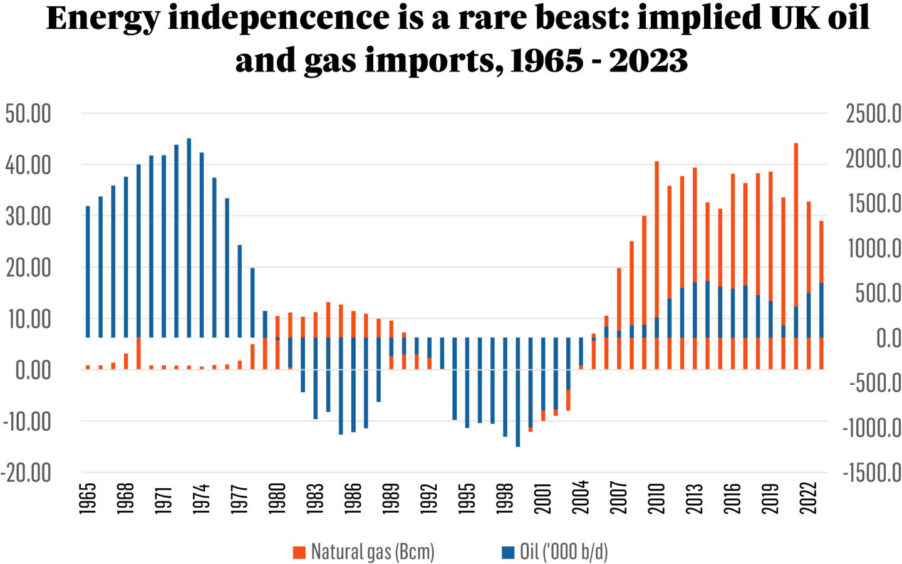

Energy independence is a rare beast, anyway, last sighted here in 2005 for oil, 2003 for gas and never post-1965 for coal. And it does not correlate with economic success.

Russia is “energy independent”, so is Nigeria. These are petro-economies, arguably even more exposed to international market prices not because they depend on energy imports, but for precisely the opposite reason, because they are energy commodity exporters.

In contrast, successful economies are typically import dependent because they have the skills and sophistication to turn raw materials into higher value-added goods. Import dependency is not a causation of economic success, of course, more an unwanted side-effect.

The US can legitimately claim energy independence as a result of its shale revolution, but it became a rich nation as a massive energy importer. And the world’s new economic superstar? China is chronically energy import dependent.

Oil and gas retreat into the sunset

Labour’s plans for energy independence are not, in any case, based on a revival of the UK’s oil and gas sector.

The government will respect existing licences, but not issue new ones. It will raise the Energy Profits Levy from 35% to 38% but retain the Energy Security Investment Mechanism , which could, in theory at least, remove the EPL, if oil prices plummet for a sustained period, a possibility which lies primarily in the gift of the OPEC+ group And Labour will remove “unjustifiably generous investment allowances”.

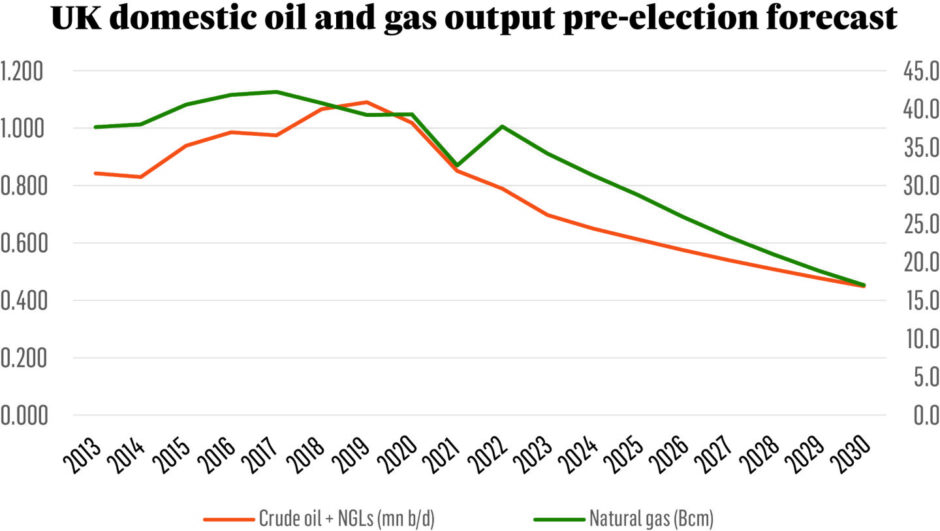

Increasing the windfall tax, taking away the investment offsets and stopping the issuance of new licences all suggest a less attractive environment for investment in UK oil and gas and therefore a quicker decline in output than forecast before the election.

Energy independence and the transition

“Energy independence” under Labour is something different.

The manifesto took some big swipes at utilities. Labour’s policy, backed by the establishment of the publicly owned clean energy company, GB Energy, places significant focus on local energy generation. The energy independence Labour talks of is, at least in part, consumer and community independence from utilities and the “broken energy market”.

Moreover, energy independence from fossil fuel markets, foreign and domestic, will be achieved not through surplus production, but from the demise of demand.

The first step is total decarbonisation of the power sector by 2030, which could indeed free electricity generation and power prices from dependence on natural gas imports. And, as consumers know to their cost, gas-fired generation in the UK’s electricity market tends to set the price for all generators.

The government will double onshore wind capacity by 2030, triple solar capacity and quadruple offshore wind. If these targets were achieved, based on 2023, which was a year of low average wind speeds, wind and solar energy generation would jump from 95.9 TWh to just over 300 TWh – just shy of the UK’s total electricity consumption last year. Throw in hydro, nuclear and biomass and the total moves to about 385 TWh, allowing some margin for electricity demand growth and target undershoots.

Hitting these targets will be tough

The most important component of this expansion is offshore wind, which is also the sector least likely to achieve its target.

No awards were made in last year’s mismanaged contracts for difference (CfD) round. Major projects awarded in previous rounds have been cancelled as a result of supply-side inflation, reflecting delivery capacity constraints. This left the Conservatives’ 50 GW by 2030 target highly uncertain, let alone Labour’s quadrupling of capacity, which implies nearly 60 GW.

Given the length of time offshore wind projects take, there is little time to get the sector back on track for 2030. Developers will also be turning their attention to the renewed possibilities of onshore wind and solar, which might detract from offshore activity.

But even if power sector decarbonisation by 2030 were achieved, it would deliver only partial independence. The impact on oil consumption will be slight as the power sector does not use much oil. It would imply a reduction in gas demand of about one third, or 23 Bcm/year, not much more than the decline in gross gas output forecast by the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) before Labour’s increase in the fiscal take.

As greening all power generation by 2030 is ambitious, there will not be surplus power to also produce the renewable liquids and gases that could replace imported fossil fuels, even if the conversion processes were commercially viable, which they are not.

Electrification where possible in the heating and transport sectors will reduce demand for fossil fuels, but also increase power consumption, which could mean falling back on the reserve of gas-fired power plants Labour says it will maintain.

The UK’s oil and gas import dependencies could, in fact, increase.

This does not mean that Labour’s ambition is wrong. To hit climate targets, power sector decarbonisation must be accelerated. Fossil fuel demand must fall. But to increase energy independence and security, UK oil and gas production should also be sustained, if not maximised, until demand falls sufficiently to match domestic output.

Uphill struggle in the right direction

Labour’s Clean Energy Superpower idea goes a step further and maybe a step too far. A clean energy superpower implies energy independence via the mass export of renewable fuels, but this scenario is well beyond the term of one or even two parliaments. It is also perhaps a macho phrase rooted in the world of petroleum power plays – the world Labour presumably wants to leave behind.

Does a successful green economy need to be a clean energy superpower? Maybe clean, competitive manufacturing and technology sectors – which add value to raw materials imported or domestic – would be enough.

Genuine energy independence, in reality, means neither a deficit nor a surplus, but a balance – just as the world needs a better environmental balance. If energy independence is genuinely the goal, then pursue self-sufficiency. The achievement of this, in the short term, means the best use of all local resources – renewable or otherwise.

Ross McCracken is a freelance energy analyst with more than 25 years experience, ranging from oil price assessment with S&P Global to coverage of the LNG market and the emergence of disruptive energy transition technologies.

© Supplied by Energy Institute/ DC

© Supplied by Energy Institute/ DC © Supplied by NSTA/ DC Thomson

© Supplied by NSTA/ DC Thomson