Steve Beedie is speaking down the line from Edinburgh where he has just finished giving a speech.

The bluff, plain-speaking Aberdonian author and business speaker is still fizzing with energy from the event, where he spoke about his new book, Open The Bleed Off, which discusses mental health in oil and gas.

The sun is shining and he’s sitting in a New Town pub sipping a pint of Guinness.

Life is good.

Just under ten years ago, however, Steve was one of the thousands of north-east oil and gas workers suddenly out of a job as the 2014-16 downturn ripped through the economy.

Part of a drill crew on a north sea rig, Steve and his colleagues were told in blunt fashion by managers who didn’t mince their words.

Those in charge held out hope the jobs would return when the industry recovered, but for the men on the rig it was game over.

Steve lived on his savings for as long as he could, eventually selling his car. Others were less fortunate — one of Steve’s colleagues took his own life in the immediate aftermath.

It was a seismic shock that continues to have repercussions in across the north and north-east.

“We just got decimated,” Steve says. “It was absolutely horrendous.”

The downturn starts

North Sea oil was already in a precarious position when the downturn fully hit in 2015.

On the rigs, workers spoke in hushed tones about the state of the industry and what that meant for livelihoods.

But when the cuts came, no one expected their severity.

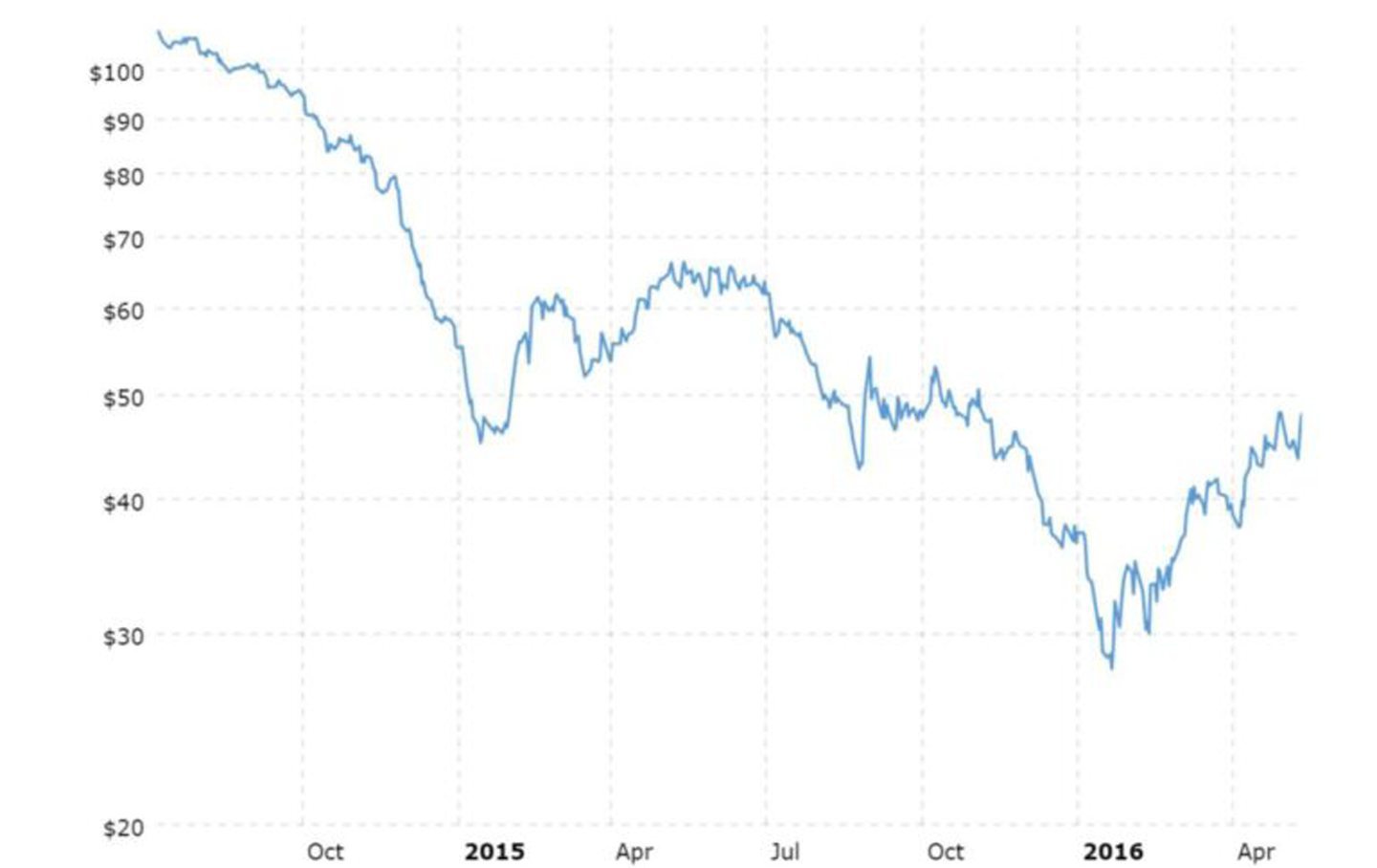

A spiraling of oil prices triggered an unprecedented downturn for North Sea energy from 2014-16.

On June 20, 2014, the price of a barrel of Brent crude — the market barometer for North Sea oil prices — stood at a shade over US$112. Six months later, that price had halved, and by the beginning of 2016 was less than US$30 a barrel.

Tens of thousands of jobs were axed on and offshore as oil and gas companies tried to navigate the slump, which was triggered by a jump in production of US shale gas and maneuvering by OPEC, the body representing large oil-producing countries mainly in the Middle East.

Suddenly, Aberdeen’s position as the oil capital of Europe turned from a strength into a weakness.

For years, the city was the most expensive place to stay in the UK outside of London. House prices had rocketed and hotels and restaurants were full.

In the space of a few months, all of that was turned on its head.

How the downturn affected health in oil and gas

At the centre of the storm were the people that worked in oil and gas. Well-paid manual labour jobs on rigs were axed by the thousands while support staff on-shore were also let go.

And underpinning the financial impact was the toll it took on health as workers were cast aside, unmoored from the salaries that comprised much of their identity.

“When you’ve worked offshore for a couple of years, you adjust to that lifestyle,” says Steve, who started on the rigs after leaving the army.

“I’d never known that kind of income, and it’s hard not to adjust to it. You upscale your car, you start doing the house up — that’s why you go offshore, to provide for your family and your loved ones.

“And then when it gets taken away, it is a sharp, shocking hit to the system.”

Losing the ‘things that the oil wages had bought’

Those in the north-east’s mental health services remember it as a busy time.

“There was definitely an increase in people’s thoughts of suicide and just poor mental health,” says Peterhead’s Fiona Weir-Rucroft, who in 2014 was working as a volunteer with the Scottish Government’s suicide prevention programme, Choose Life.

She now manages Fraserburgh suicide prevention charity Shirley’s Space.

Fiona adds: “A lot of folk, their lifestyle changed because they could no longer afford the things that the oil wages had bought for them or helped him maintain.”

Suicide rates in the north-east were so bad around that time that Choose Life developed a suicide prevention app that is still in use today and has been credited with saving hundreds of lives.

“It was badly needed,” Fiona says.

Uncertainty and doubt leads to trauma

In Inverness, Fiona MacAuley still deals with the trauma left behind by the downturn.

At the time it was happening, she worked for International SOS, which provides health services for the oil and gas industry including off-shore medicals.

Today, she runs Highland Trauma Services, a private counselling service that specialises in workplace mental health.

What the downturn delivered, Fiona says, was heightened uncertainty. Any sense of job security was washed away.

“Trauma is very often the straw that breaks the camel’s back,” she says. “All the pressure of the uncertainty of the downturn builds up, and then without warning people just crash.”

She saw lots of professional burnout as people failed to adjust to the changes. Physical health was also affected, with people suffering cardiac issues.

One client even had a complete change of personality, going from a laid-back, highly motivated individual to someone with high levels of anxiety.

Working with him, Fiona eventually traced the change back to childhood trauma newly resurfaced.

“Chronic depression is the most persuasive evidence-based sign of unprocessed trauma,” she says. “And if you’re working offshore, you’re dealing with a lot of people with unprocessed trauma.”

Unemployment ‘just devastating’ for Steve

Ousted from their drill crew job and newly unemployed, the trauma for Steve and his co-workers was raw and apparent.

“It wasn’t so much anger, it was fear,” he recalls. “Many had to make that phone call to their wife, their partner, their loved one. Some of these guys had kids on the way, or they just bought a brand-new house.

Steve’s frustrations came from the loss of identity that came with losing his job.

“I was wanting to progress,” he explains. “I felt like I had a bit of momentum in my career and I was looking to climb up to that next stage — assistant driller, hopefully, then driller.

“And then it was taken away from me, and I had a year and a half where I wasn’t working, and it was just devastating.

“Trying to come back after that was really hard.”

The health legacy of the downturn

Steve eventually returned to oil and gas, taking up a position as a derrickman. He still works around the world in between promoting his Unspoken Wounds initiative that encourages people to discuss their struggles with mental health.

But many of his former colleagues stayed away from oil and gas. The 2014-16 downturn differed to previous slumps because those who lost their jobs were just as likely to change careers, launch new businesses or seek work overseas.

Moves away from fossil fuels towards green energy had something to do with that as oil and gas looked for new ways of operating in line with net-zero ambitions.

But for those who lived through the downturn’s most damaging effects, the memories of the trauma left a deep scar.

“It was business,” says Steve. “I know they had to start trimming the fat off the meat, right?” he says.

“But it doesn’t feel good when you’re the one getting trimmed.”

Will it happen again?

Have lessons been learned?

Fiona in Inverness doesn’t think so.

“There is a lack of clarity between mental and physical health offshore,” she says of health care management in the industry.

She believes it is a problem that is becoming more acute. Oil platforms are getting older and therefore more dangerous.

Oil and gas workers already exist in some of the world’s most dangerous environments, but mental health will suffer more if those dangers increase, Fiona believes.

And it’s not just the assets that are old. Fiona says the typical oil and gas worker is also getting older.

“It’s really hard to recruit young people to do apprenticeships, and there is a need for that,” she says.

Meanwhile, Steve says he’s proud of the way the industry came together after the downturn to build back up.

“We did a bloody good job of it,” he says.

But as governments continue to dabble in the North Sea and attempt to chart new paths he has a warning for the future.

“If a downturn happens again, it’s not going to be pretty.”

If you or someone you know is struggling, the Samaritans have a free helpline which can be accessed 24/7 by calling 116 123, or you can email jo@samaritans.org.

The Prevent Suicide app is available for download at the App Store and Google Play. In the north-east it is also available on Amazon for Kindles.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Allister Thomas

© Supplied by Allister Thomas © Supplied by Macrotrends

© Supplied by Macrotrends © Supplied by Unknown

© Supplied by Unknown © Supplied by Kenny Elrick/DC Thom

© Supplied by Kenny Elrick/DC Thom © Supplied by Supplied

© Supplied by Supplied © Supplied by DCT Media

© Supplied by DCT Media © Shutterstock / snapinadil

© Shutterstock / snapinadil © Image: BIG Partnership

© Image: BIG Partnership