Methane emissions pose a major threat to the world’s climate change goals as the hydrocarbon is a greenhouse gas many times more damaging than carbon dioxide.

Reducing how much is released into the atmosphere would go a long way to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees.

However, despite attempts to scale them back, the oil and gas industry is still struggling with its methane emissions.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) warned this year that global methane emissions from fossil fuels neared a record high in 2023.

This comes as the industry is faced with cutting its methane emissions by 75% by 2030, the IEA said, to have a shot at reaching net zero emissions by 2050.

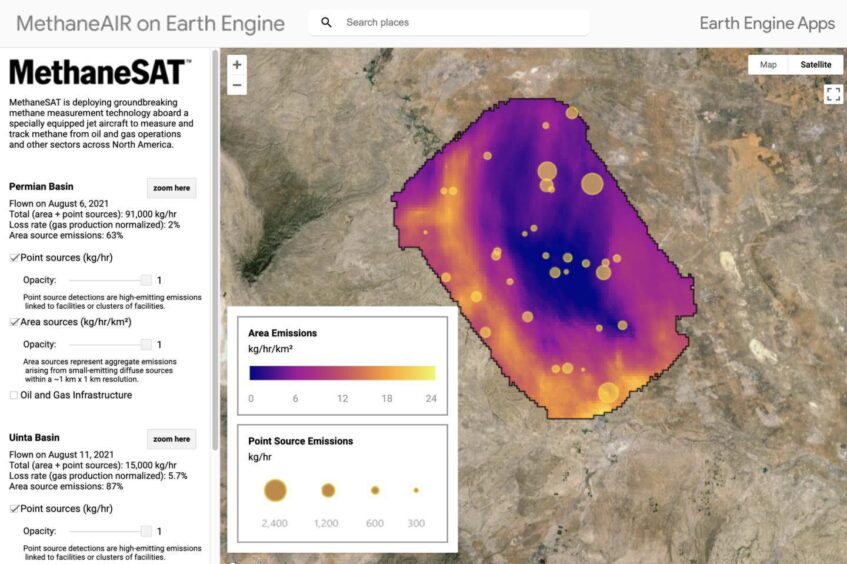

One source of methane emissions is poorly sealed oil and gas wells. Research has suggested up to 6 million tonnes of methane may be leaking from abandoned wells every year.

Edinburgh-based Rockit, a spinout from Heriot-Watt University, announced its ambitions to seal 100,000 methane-leaking wells around the world over the next decade using a chemical injection technology it developed.

This aims to curtail leaks of the climate-wrecking greenhouse gas emissions being released into the atmosphere.

Legacy wells

“We live on a huge planet,” Rockit director Oleg Ishkov told Energy Voice. “There are millions of wells drilled all over. And, for example, in the US, a lot of the work was started 100 years ago. Decommissioning standards up to the 1950s were poor, with no globally recognised regulations.

“100 years of production has left us this legacy all over the world, from the US to the Middle East, the former Soviet Union, all countries with poorly sealed wells.

“This creates a huge, expensive problem to go reseal everything,” he added.

“This is where we want to come in, with a solution that can just be pumped to improve the seal.”

As a greenhouse gas, methane has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide over a 20-year period.

While it breaks down eventually into water and CO2, methane represents a major short-term threat to the world’s immediate climate ambitions.

“If we can deal with methane now, we can immediately see a quick turnaround and payoff,” Ishkov said.

Old seals

Part of the problem is old legacy oil and gas wells. Either sealed when regulations were weaker, or subject to deterioration over time, the seals on these are no longer capable of keeping methane contained.

While work is being done to find new ways to plug and abandon wells, cement is the workhorse for the decommissioning industry. It is a cheap, plentiful material that, crucially, is proven and accepted by regulators.

“Cement is a fantastic material but it’s not perfect,” Ishkov said. “The challenge with cement is it has particles in it, so it cannot penetrate into the pores. It also has tiny apertures that are enough to leak gas.”

In addition, cement is not ductile, so after the initial bond is created, changes in temperature and movement mean it can crack and degrade.

Contaminants and impurities such as muds can prevent the cement setting and bonding properly.

“There are a lot of complexities around these conditions,” Ishkov said. “There is a lot of evidence of leaks, especially onshore in the US.

“What we are offering is an improvement that can protect cement from degradation.”

New solution

Ishkov was part of Heriot Watt’s Flow Assurance and Scale Team (FAST), focused on oil and gas, specifically working with ways to prevent scaling.

When oil is produced, especially in subsea wells like in the North Sea, it comes with huge amounts of water. Handling and disposing of this water creates numerous issues, including scaling, where minerals dissolved in the water precipitate out of the liquid to deposit on pipelines and other infrastructure.

One specific mineral is called barium sulphate.

“It blocks perforations and pores, it sits inside tubing. It’s like you have veins in your body and this is the cholesterol,” Ishkov explained.

Having worked on preventing buildups of barium sulphate in the past, when Ishkov began exploring decommissioning, he spotted a way to use his expertise, but this time in the opposite direction – encouraging the buildup of minerals inside a cement plug.

Rockit’s system uses a chemical injection method which transforms permeable rocks into a solid, permanent store of methane.

“The idea is we will force in a lot of minerals out of an aqueous solution to form those minerals and to block the pores, so the wellbore is sealed,” he said.

Rockit’s solution is designed to infiltrate even the smallest pores and cracks where existing methods fall short.

This can offer a more effective sealing method for both shallow onshore and deeper offshore wells.

“What we do is essentially precipitate a rock inside the rock,” Ishkov explained. “Barium sulphate is a material found in geothermal wells, it can withstand enormous conditions. It’s a natural material. It’s formed like millions of years in the Earth’s crust.”

This helps deal with one issue around resealing abandoned wells – expense.

For more recently drilled wells, the operators and owners are typically the ones to foot the bill, with a clear chain of ownership established.

But for many older wells, where the owners may have gone bankrupt or otherwise cannot be traced, liability can fall to the taxpayer to seal these so-called orphan wells.

“At the moment, 100,000 orphan wells have been identified, but that may only be 10% of the problem,” Ishkov said.

“This is the crisis – we have a climate crisis and we have a crisis of legacy of industry.”

Future industries

But properly sealed wells aren’t just about combating climate change. It sets the stage for future North Sea industries.

“The North Sea has a lot of legacy wells, so we have very good storage candidates for CO2, but some of those legacy wells were not abandoned to the standard.”

Rockit has said that its technology could also have broader applications beyond preventing methane leaks, including enabling carbon and large-scale hydrogen storage.

“The UK has a huge potential for CO2 storage,” Ishkov noted. “There are areas where we can store a lot of CO2, probably some of the best in the world.”

“But the problem is that CO2 and water create acidic conditions. This degrades the cement. It would be a stupid idea to put your CO2 underground for thousands of years and it leaks.”

Not only would this release a huge amount of greenhouse gas if left unattended, the cost reintervening on a well can be enormous, sometimes 10 times more than the cost of the initial P&A.

In addition, depleted reservoirs can be used to store hydrogen produced by renewable energy sources.

“The problem with hydrogen is it’s a very small molecule,” Ishkov noted.

This means it can easily escape through even small pores, making a tight seal vital to keep it contained.

Geothermal is another potential use for legacy North Sea wells.

“With geothermal, the margin is also very low. If you have leaks, you lose temperature, you lose your working agent.”

However, Rockit aims to focus on the onshore US wells, as these represent an easily accessible group of its planned 100,000-well target.

“We’re focusing on onshore and the US, where there are millions of wells,” Ishkov said. “So out of them at least 30% leak and the seals don’t hold properly. So 100,000 is a manageable number – this is how we feel that we can make an impact.

“Those wells will contribute tens of millions of tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions. So the number is ambitious, but if you look at the number of wells globally and how many well work over operations are, it’s doable.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Heriot Watt

© Supplied by Heriot Watt © Supplied by Google Earth

© Supplied by Google Earth © Supplied by system

© Supplied by system